|

|

|

|

The Poison Pie Publishing House presents:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

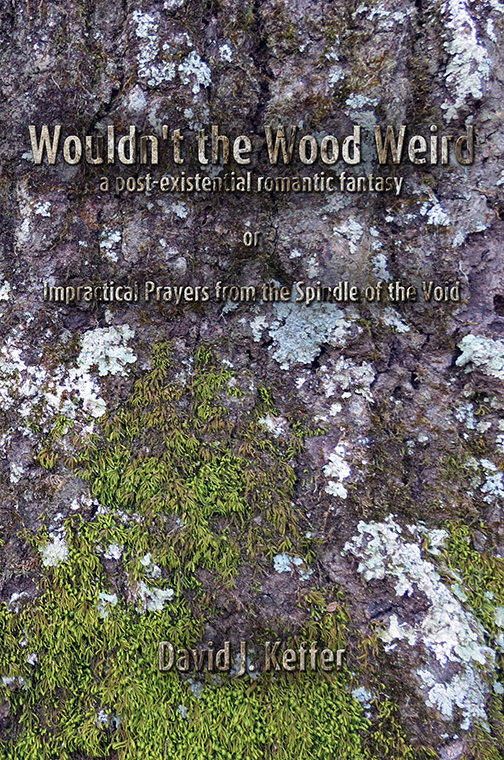

Wouldn't the Wood Weird

a post-existential romantic fantasy

or

Impractical Prayers from the Spindle of the Void

(link to main page of novel)

December

|

|

|

|

|

December 15, 2018

Lake View Park

The town in which our story takes place was predominantly situated along the northern banks of a river. This town had its origins in the 1700's when the population of the area was small and land was plentiful. The town expanded from east to west along the river. At a substantial bend in the river, where a promontory of land was wrapped on three sides by a watery ribbon, a sizeable neighborhood of well-to-do citizens took root. Only centuries later would the value of the property be tied to its proximity to the river front; at that time periodic flooding rendered some plots undesirable. As such, a wealthy doctor convinced the administrators of the city to cordon off almost two hundred acres of river-side real estate for the establishment of a public sanitarium, of which he was named director.

There was little objection to this arrangement because, in this era, only the deranged relatives of the wealthy were admitted to such institutions. Thus their new neighbors would, by and large, be known to them. In contrast, the mentally ill from impoverished neighborhoods were tended to (or not tended to) in what homes they had by whatever family would care for them.

The grounds of the institution rose from the river bank to a wide flat plateau, initially a flood plain, though once the river was dammed far upstream and the local floods rendered a thing of the past, this expanse served only as a broad grass-covered meadow in which vigilant nurses kept patients from straying too close to the water. Above these fields, the ground rose gently again in a series of sloping hills and small terraces to a crest, upon which the sanitarium, a severe, brick, three-story rectangular edifice stood. The central building was, in time, joined by a second building almost as large and half a dozen much smaller ancillary structures.

Because the doctor, genuinely committed to his cause, spent a great deal of time at the sanitarium, he endeavored to create a naturalistic paradise as much for his own pleasure as for that of his charges. As a result of his efforts as well as those of subsequent, like-minded directors, the grounds were recognized as an arboretum in their own right. On the terraces, beneath the sanitarium, oaks grew from acorn to giant white oaks over the span of centuries. Lining the drive from the gated entrance, orderly columns of tulip poplars stood as sentinels. An array of other species--locust, sugar maple and black walnut--were scattered behind them. Farther down the slope, capping the flood plain at the east edge of the property, a copse of native deciduous trees, ash, boxelder, sassafras, river birch and sweetgum remained untouched. At the western edge of the flood plain, a dense grove of hemlock kept to themselves.

When the sanitarium celebrated its bicentennial anniversary, it had become a more democratic institution, at least in terms of the degree to which its residents represented the population of the state as a whole. At the same time, it became the subject of local scrutiny. As the city had grown in size, the prosperous residents of this neighborhood began to resent the fact that they shared their expensive riverfront views with insane strangers. Under the guise of concern for the patients, the local residents noted that the facility failed to meet modern safety standards. They convinced the leaders of the municipal government, some of whom were neighbors, to petition the state to invest in a new institution much better suited to care for the patients and located, as it turned out, far from the river, on the border with a rural county.

It took some years to accomplish this task, but when the last patient had been transferred, the local neighborhood council put forward a long-simmering motion to convert the grounds into a park. The transformation required almost no additional upfront funding for the flood plains were natural soccer fields as they already stood and the trees spaced along the gentle hills provided ample shade for family picnics. As for the sanitarium itself, the largest two structures were left standing, their entries chained shut, at the top of the hill. The smaller buildings were demolished and the debris hauled off in a matter of weeks, leaving several gravel-covered footprints that served as parking lots. The neighborhood council voted to retain the name of the sanitarium, "Lake View" for the park. It was a city park and therefore open to the general public; the iron fence remained, but the gates were removed. Of course, owing to its proximity, it was primarily visited by the local residents.

This story, which I have decided to tell, describes three individuals, who had each spent some time at Lake View, when it still served as a sanitarium. Each had suffered a malaise of the mind and had recuperated under the careful ministrations provided on these restorative grounds. Each had reason to return to Lake View in its subsequent incarnation due neither to its undeniably pleasant attractions as a park nor due to nostalgia for a location in which they had, each in their own way, recovered their health. On the contrary, they returned to Lake View for the very explicit reason that they were drawn to a fourth, former resident, who had resolved never to leave the premises. His name was Wōden der Udwyrd, but due to a combination of a speech impediment and the foreign-sounding nature of the name, almost everyone called him Wouldn't the Wood Weird.

|

|

|

|

|

December 16, 2018

Wouldn't the Wood Weird

It falls to me to introduce our quartet of protagonists. The knowledge that these four individuals were former patients of a sanitarium may be sufficient information to dissuade some readers from continuing further with this story. After all, few want to spend their leisure time dwelling on the miseries, real or, worse yet, imagined, of others. In an attempt to quell such worries, let me reassure the reader that I have no intention of providing a clinical diagnosis of their respective psychoses nor do I have any stomach for plumbing the depths of their madness. On the contrary, I hope to present them much as I would describe myself or you, Gentle Reader, for that matter, namely as a reasonable person with idiosyncrasies that fall somewhere along the spectrum of personalities ranging from the unusually conforming to the unintentionally eccentric. I am prompted to provide this initial disclaimer only to forestall the natural objections with regard to populating this story entirely with those who have wandered through mental illness.

Many people distrust institutions and choose not to associate themselves with them. Even those who do embrace a particular externality have moments when they regret doing so. One need think no further than the sports fanatic who burns his jersey in reaction to the colossal blundering of his favorite team, whether it be on the field or in the management office. Other institutions, sometimes judged to be more appropriate to receiving one's loyalty, such as one's government, are often revealed through the diligent work of journalists to be so rife with corruption that they harbor the honest allegiance of only the very gullible. Even institutions of morality, the Church in particular, are all too frequently subject to scandals that test the tolerance of the faithful. These arguments are presented in order to place Wouldn't the Wood Weird in the appropriate light, for the most unusual characteristic of Wouldn't was his utter detachment from all human institutions. Although the extent of his rejection may seem excessive, perhaps even to the point of madness, the motivation behind it should not feel alien to us.

Wouldn't observed that all human institutions were deeply flawed, more flawed he thought than the cumulative sum of the flaws of the individuals who comprised them. A synergy of error arose from the collective actions of humans that drove Wouldn't to eschew them. Of course, Wouldn't was himself a human being and subject to the same category of errors as his fellows. Far from considering himself an exception to the rule, he perceived himself with a more critical eye than he did any others. It was through this excess of critical introspection that the seed of his illness, if we dare call it such, was born.

Wouldn't the Wood Weird felt called, as many do, to contribute to a general, altruistic effort that is commonly described as "making the world a better place". Yet, he judged himself, based largely on a history of errors and aborted attempts, incapable of doing so. Therefore, Wouldn't the Wood Weird resolved to become a tree.

Trees make the world a better place simply by existing. There is intrinsic to their nature a benevolent and palliative element. Effortlessly and without lament, trees participate in the various processes of the dynamic, geobiophysical system that constitutes our global ecosystem. As only one example, trees play a critical role in maintaining the compositional balance in the atmosphere appropriate to life by converting carbon dioxide to oxygen. Despite their grand role, trees have never let their egos take control of them. No tree is too high and mighty to offer shade on a sunny day to a weary passerby, no matter the color of their skin nor their station in life.

Wouldn't the Wood Weird was a man of uncommon resolve. He did not merely aspire to become a tree. He became a tree, which is why he never left the grounds of Lake View after the sanitarium was closed. It was also why the other three returned to Lake View, because, through his ministrations, rather than the regimen of psychological and pharmacological therapies of the physicians, they found what healing they could.

|

|

|

|

|

December 17, 2018

Samudra the Drowned

When Samudra was a child of five, she happened to witness a neighbor's daughter drown in the stretch of river beside her village. The child, who knew how to swim, had simply strayed too far from shore. Her head disappeared from view. It took a minute for the assembled throng of children to convince the mothers gathered doing laundry on the shore that there was a problem. An understandable panic ensued. Later in the afternoon, the body was discovered washed ashore downstream. While she witnessed the hysterical lamentations of the girl's mother, Samudra herself experienced little overt trauma.

However, it is difficult to deny any connection between that incident and the subsequent fixation with drowning that came to consume Samudra. Naturally inclined to introspection, she began innocently enough by imagining what it was like to drown. She contemplated the physical and mental processes in minute detail, holding one's breath until biological impulses filled the lungs with water as well as the accompanying mental resistance that gave way to panic then to a dim resignation then darkness. Although she entertained such thoughts with increasing frequency, she knew that if she shared her obsession with her mother, she would receive only an upbraiding for being impractical, no less than if she had pestered her with fantasies about becoming a movie star. Therefore, Samudra kept her drowning fantasies to herself.

When her father won an immigration lottery and the family moved from the developing world to the developed, Samudra was placed in middle school and the fascination, which had not left her, moved with her.

In high school, her classmates liked Samudra well enough. She possessed an intelligent smile, a thoughtful voice and a quiet demeanor that attracted friends to her. To none of these friends did she confide that she woke each morning to thoughts of drowning nor that she retreated to these comforting, familiar daydreams during the doldrums of class. There she found a peace of mind in the muffled silence of water. The mundane trials and tribulations of life were put properly in perspective when projected against a watery background possessed of the significance of life and death. When talk of suicide arose, as it must among teenagers, she discovered that she did not share the opprobrium for suicide of her peers, who, having been raised according to the traditions of the Christian god, believed that Heaven was denied suicides. Samudra entertained a very different, personal theology, in which an eventual, solemn drowning, to occur much later in life, would be a welcome transformation to an unknown but suitably calming afterworld.

When she was an undergraduate studying economics at the local university, Samudra experienced a new revelation. She had lived fifteen years imagining many times each day that she had drowned. By her calculations, she had simulated drowning more than thirty-two thousand times. It occurred to her that perhaps one of the times she had actually carried out the task. That she was unaware of the truth of her drowning was simply a result of the real act being sandwiched between so many imagined mirror images of it. If this was the case and she had in fact already drowned, then what she experienced now as life was not genuine living but a production, orchestrated by unknown powers, of what might have been if only she been able to hold off for a longer time. Perhaps influenced by the thoughts of her Christian neighbors, she suspected that the purpose in the necessity of her observing the recording of her lost life to its conclusion was punitive in nature. She was being forced to see the wonderful chances that she had missed by drowning too early. In order to minimize the severity of the punishment, Samudra took to consciously avoiding people and activities that she could reasonably expect to enjoy. In that way she rendered the life that she had not lived less memorable and its loss less damaging. Through this process, it is important to note in understanding Samudra's character that she remained an intellectual rather than emotional interest in her relationship with her, admittedly unhealthy, obsession.

Only one more step in the chronological sequence of Samudra's state of mind shall we include here. When she turned thirty, she came to the realization that there was little purpose in keeping her more than daily routine of drowning to herself. What was the point in living a lie? She finally succumbed to the message of individual self-expression that ruled the culture of the day. For her, there was nothing more intrinsic to her being than the routine ritual of immersion and inhalation of water. She therefore in fits and starts communicated to her friends and family her secret history of drowning. Once a trickle began to flow, the flood gates soon opened and a torrent followed. Alarmed and fearing for her welfare, Samudra's parents, with the best of intentions, arranged a regular schedule of therapeutic sessions with the caring staff of the Lake View Sanitarium.

|

|

|

|

|

December 21, 2018

An Invitation

From the perspective of one of the several Lycra-clad joggers exercising along the paths through the park, the woman seated alone beneath the oak tree, from which the leaves had fallen weeks earlier and already been collected by city workers, was speaking to herself. They quickened their pace as they passed her. The gray skies overhead threatened rain but only a tiny fraction of a drizzle had yet materialized. Each pedestrian hurried to complete their morning routine, for the chill of autumn was well established and they hoped to have returned to the warmth of their homes before the rain began in earnest.

As such, Samudra and Wouldn't remained undisturbed.

One runner, a mother who was particularly concerned about safety issues in the park where her children often played, gave more than a passing glance to the woman. She momentarily thought that she detected the shape of a homeless man, bundled in a brown coat, lodged high up in the bare branches of the oak. However, when she looked again, she saw only the exposed, bulky but empty nest of an eagle, birds known to raise their young during the summer over local stretches of river. She too left Samudra to her own devices.

This illusion of the man in the tree was not without some cause, for Wouldn't was both man and tree and often manifested in an unresolved state between the two.

"I am," said a voice like the sough of the wind originating from an unoccupied spot among the boughs and twigs, "assembling a team."

With her back against the trunk, cushioned by the stuffing of her winter coat, Samudra tilted her head up and examined the palette of grays segmented by the pattern of the branches, projected against the canvas of clouds. "Was that an invitation?" she asked. "What kind of team?"

"A team," said Wouldn't, "to Make the World a Better Place."

Samudra lowered her gaze and looked out across the fields to the river and across to the far bank, a collection of empty pastures separated by tree-lined gullies. She took her time in replying for she gave little thought to escaping the rain. When she did speak, her objection was muted. "I'm not sure that I would make a good member of such a team." We can forgive her this minor indulgence in self-doubt; it was present only in a proportion that many of us might find familiar.

"Of course you would," Wouldn't immediately replied. "You have exactly the one quality essential for membership."

We picture Samudra as she searched within herself, trying to discover the trait of which Wouldn't hinted. Her brown eyes were wide and alert; her black hair parted in the middle of her forehead and was draped, in two straight bands down past her shoulders, where it spread in thinning fans over her coat. She appeared very clean; her fine hair washed earlier in the morning, her complexion clear, the wool of her coat marked only by tiny clear droplets of condensation. Giving up, she asked, "What is it?"

"You have come through fire," said Wouldn't, beginning in a whisper. "You have been tempered and hardened. If you are not at peace with yourself, if you are battling internal demons, you can't hope to direct your energies outward, to be in a position and state of mind to tend to the suffering of others. But you were discharged from Lake View. You have conquered your demons. You passed the boot camp and are ready to join the team."

Samudra stared out over the water as she listened to the words of the tree. After a while, she said, "I will consider your invitation." She looked back up at the empty boughs of the tree. "But, for the record," she added, "I was always at peace with myself, even before my parents sent me to Lake View."

"Of course, of course," agreed Wouldn't without sarcasm. "You are perfect. You will naturally rise to a leadership position within the team!"

Samudra directed a pleasant smile toward the tree and rose to her feet. Before she departed, she asked, "Is there anyone else on the team or is it just you and me?"

"Samudra!" said Wouldn't feigning indignation. "You are admittedly wonderful but you are not as unique as you may think. You are not the only former patient, since Lake View closed, to have acted on the impulse of returning to visit me."

|

|

|

|

|

December 22, 2018

Ohu the Threatening

In the incomplete versions of this story found on scraps of mildewed parchment dating to the mid seventeenth century, the tree and the drowned woman are next joined by a third individual. In some accounts, this woman is described as a sylph, a spirit of the air, a contraction of sylva (forest) and nympha (nymph). An association with the element of air bestowed upon this woman a transparency of intent, a buoyancy in approach and the fickle nature of the changing winds. In other accounts, she appears as a psychic, receiving information from sources beyond human understanding. In this role, she tends toward translucency, for though she is willing to share her insights from the spirit world, she frequently cannot explain them. As psychic, she retains, however, the full measure of her fickle reputation, for she cannot control the timing or origin of her insights, nor can she shape the outcome of her pronouncements. In the current retelling, we opt to present this companion as a combination of sylph and psychic, by which we expressly convey the spiritual nature of both her intrinsic being and her functional role. In terms of assigning her a name, we adhere to the traditional Ohu, which in some languages of the north, is rendered as 'threat'. We intend for the reader to understand that Ohu herself was not deemed a threat. Rather, her visions, often dire, threatened the freedom of those whose future they described, by confining them within the stricture of determinism, an unpleasant fate no matter how ill-founded and absurd its origin.

|

|

|

|

|

December 23, 2018

Secret Powers

Ohu moved constantly around Wouldn't as she talked. Her words flowed in a continuous stream in which momentary observations that had caught her eye and lodged in her memory on the way over--a child pressing his face to rear window of a car in front of her--shared space with the ostensible purpose of her business. Her ankle-length skirt, cut from a floral-patterned fabric, whisked this way and that, as she abruptly changed direction. "Besides," she said, pushing the sandy blond hair that had fallen in front of her hazel eyes back behind her ear, "how could it take you so long to realize that you were meant to make the world a better place?"

Wouldn't watched the wispy frame of the woman dart back and forth with pleasure. He particularly enjoyed her company and her idiosyncrasies. It reminded him of when a flock of sparrows landed en masse in his branches. "I'm just a slow learner, I guess," he said happily. He was fully reconciled with the notion that he had been a late comer to the cause of wisdom.

"What's more," said Ohu, ignoring his answer, "you're doing a crappy job of it." She laughed after she declared this judgment, as if there were humor in the failure of Wouldn't.

For his part, he delighted in the sound of her laughter, as unpredictable as the tinkling of chimes in breeze.

"Look at the sad state of affairs," Ohu continued. "The world is a mess." At home there was rising inequality. In their nation of riches, many millions of children went to bed hungry. Abroad, authoritarian rule collapsed leaving ruins from which the chaos of tribal conflict, decades buried but not forgotten, made victims of all. Both abroad and at home, terrorism grew. "Even if you had started earlier, I'm not sure it would have made much of a difference." She spread her hands apart when she was done to equate the nothing between them with the fruits of Wouldn't's efforts.

Wouldn't listened patiently to Ohu. "Ohu, my friend, you have misunderstood me. A tree makes the world a better place just by being a tree."

The woman replied so quickly that Wouldn't suspected she had not allowed sufficient time for his words to penetrate her thinking and influence her reply. Still, it was not his way to repeat himself. "Wouldn't the Wood Weird!" She giggled at the funny name. "What good can you do as a tree?"

Attracted by the sound of her voice, a black cat that frequented the park, called Charcoal by the local children, approached. Their conversation paused as the animal neared.

Ohu made beckoning noises as the cat drew close. It rubbed against her legs. She squatted to scratch its arched black. "Imagine this," she said to Wouldn't in a voice of rising drama. "A black cat crosses the path right of front of you." She pointed to the greenway that skirted in a bend around the bulk of Wouldn't, well beyond the reach of his branches. "An unsuspecting pedestrian is absorbed in her texting. She is about to cross the path of the black cat and be stricken by proverbial bad luck. What can you, a tree, do to prevent her fate?"

Wouldn't wiggled his branches. Put on the spot, he feared that he would be unable to rise to Ohu's challenge. This was not the way the contemplative tree had been intended to function. Still, he struggled to oblige. What could he do to save a single pedestrian from bad luck? Suddenly, the answer occurred to him. He could do nothing! He could not influence events beyond his control, not for one and not for many. What he could do was make the experience of bad luck as palatable as possible, infecting it with a seed of wisdom if not joy. The only way to accomplish this, of course, was to present himself in the full majesty of an oak tree, which, since bygone ages, brings comfort to many who adore the grand shapes of living things. Those of us who have marveled at the beauty of an old tree know exactly the path and pace of Wouldn't's reasoning.

To Ohu, Wouldn't replied simply, "I would use my imagination."

Ohu very much wanted to insist that imagination didn't make the world a better place, but she could not bring herself to voice the words, at least not in the presence of Wouldn't the Wood Weird.

|

|

|

|

|

December 24, 2018

Coffee

The two women sat in a corner of the coffee shop on Saturday morning. Samudra had paid for both coffees since Ohu was still surviving on her meager checks from disability welfare. Samudra had not inquired regarding her current job search nor her housing, since she knew both were always in flux and did not want to invite a lengthy and overly detailed tale of opportune chances thwarted by casual but inevitably untimely turns of circumstance. Ohu's telephone call to arrange this meeting had come, according to Ohu, from the common landline in the office of a building of subsidized apartments. Samudra had drawn some comfort from the knowledge that Ohu was out of the wet, winter weather.

Ohu's attention darted from one face in the coffee shop to another, settling on each only for a moment and moving on before her attentions were deemed excessive. Periodically she returned her focus to Samudra who sipped her coffee, black and without sugar, in silence.

"Wouldn't says he's going to make the world a better place," Ohu said as if agitated by the idea.

Samudra nodded. The two women were roughly the same, average height and shared a similar frame but the resemblance ended there. Samudra, introspective by nature, projected a calm and quiet demeanor, whereas Ohu could not contain the energy inside her and communicated in a ceaseless series of interrupted fragments. Though a decade younger than her companion, it was Samudra who seemed the more composed. "I have every confidence in him," she said, hoping to soothe Ohu's anxieties with these thoughts.

"I don't understand how this is going to work," Ohu admitted with a note of warning. What she really meant to convey, of course, was that she had already received a vision that all the efforts of the tree would come to naught--a frequent message from the spirits that guided her.

"You don't have to understand," Samudra assured her. She added in a conspiratorial tone of complicity, "I too don't understand."

Ohu smiled. "You always know when to say the right things."

At the compliment, Samudra returned the smile.

Both women sat in silence for a while, nursing their coffees. Samudra's thoughts drifted off. Ohu continued to scan the customers at the counter. When her attention returned to Samudra, she watched her intently. After a while, Ohu became impatient. "Are you drowning?" she asked the woman across the table.

"What?"

"Were you just drowning yourself right then?"

Samudra looked around to see if anyone had heard the remark. After the unintended consequences of her first attempt at openness, she had resumed her habit of keeping her fantasies private. There were only a few outside her parents and therapists--Wouldn't, Ohu and Tony--who knew the truth. Only Ohu would speak of it openly as if it were an innocuous habit, like reading romance novels or knitting. "No," she answered. "I was just..."

Ohu didn't allow her to finish. "Are you always alone when you drown? Do you think," she paused and fixed the woman with a serious glare, "that you could do it with me?" Seeing the perplexed look her questions induced, she added, "Just once."

Samudra had no desire to talk about this any longer. Having thought of Tony, she changed the subject, "Wouldn't says we need Tony, though I can hardly imagine why."

"I'm afraid of Tony," admitted Ohu, "sometimes."

"Oh stop that," Samudra chided her. "You have nothing to fear from Tony."

"Anyway," Ohu said, "we'd never be able to find him, even if we wanted to."

"We could take out a classified in the paper." In fact, this was just what Samudra had been thinking about doing.

"Do people still read papers?"

"If anyone does, it would be Tony."

"What would the classified say?" asked Ohu. "Three conspirators--two women, one tree--seek disease/drug-free man with four arms?"

"Exactly."

|

|

|

|

|

December 30, 2018

Three Manifestations of the Void

His wife had never called him Tony. In fact, only the third syllable of his real name bore a passing resemblance to any syllable in Tony. Still, he adhered to the local adage, "When in Rome, do as the Romans do." Thus he conformed to a variety of customs, which he deemed relatively innocuous. Such a flexibility of habits was a prerequisite for a far-ranging astronaut such as he.

Space travel requires a particular sort of mental make-up, combining an admiration for discipline and a disregard for discipline in equal portions. Confinement within the restrictive habitat module for extended periods of time could be rendered hospitable only through the integration of these two seemingly contradictory elements. An astronaut had to maintain a strict physical and mental regimen, in order to keep body and mind fit. Otherwise muscles would deteriorate under the weak gravity and the circumlocutions of the mind would succumb to the vast distances of void that surrounded the craft in all directions, as it hurtled through emptiness.

It was essential that astronauts also knew when to abandon discipline when circumstances changed and their established routine no longer served them well. Largely, though not exclusively, applied to matters of the mind, the ability to independently recognize the inadequacy of one's current habits and move beyond them into unknown territory had proven critical to the survival of the astronaut, after their ship had crashed.

Certainly, Tony would not suggest that the Earthlings had been anything but accommodating. They had earnestly misdiagnosed him as suffering from psychiatric disorders and obligingly placed him, at the expense of the state, in an institution suited for the recuperation of such individuals.

In truth, Tony had been damaged by the voyage, if not the crash itself, and the efforts of the Earthlings were not entirely wasted. Again, we shall not belabor the reader with the recitation of a lengthy litany of the astronaut's ills. Rather, we shall limit ourselves to the three most debilitating ailments, all of which were related to the void. We shall begin with the most external and travel inward.

First, the astronaut had lost his wife. When he woke from the crash, she was not to be found in the other bed in his room. All inquiries regarding her condition and whereabouts were met first with blank stares. Initially the hospital staff made significant efforts to locate her; it would aid in the billing if nothing more. As time passed and their search proved unsuccessful, they began to ask more penetrating questions, such as "Where had they been married?" and "Had they been divorced?" His strange answers to these questions first led the doctors to suspect that he was a widower. Later, his inability to provide clear details led them to believe that his wife was in fact a figment of his imagination.

Regardless of her origin, her absence left a terrible void in the astronaut's life, for, over the years they had shared in the close confines of the spacecraft, he had come to find great comfort in her physical presence. Deprived of this comfort, he proved unable to entirely eliminate a pervasive and ambiguous anxiety.

Second, the astronaut had lost, apparently in the crash, his second set of arms. On his native planet, all persons were born with a full complement of four arms. When he awoke in the hospital, he discovered, much to his dismay, that he only possessed two arms, one on each side, connected to his shoulders, in exactly the manner of the Earthlings who tended to him. In truth, in the absence of these additional appendages, he appeared no less human than anyone else. "What have you done with my arms?" he cried, for he originally suspected that they had been intentionally amputated by the doctors, so that he might better conform to their planetary standards. Everyone assured him that he had arrived at the hospital with only one pair of arms. Numerous physicians attempted repeatedly to convince the astronaut that he had never possessed more than one pair of arms. The astronaut knew this to be false, for he suffered direly the disorder known as 'phantom limb pain', often experienced by amputees in the extremities that they no longer possessed.

Third, the astronaut had apparently spent too much time cocooned in the vacuum of outer space for he had allowed a speck of void to infiltrate his being. Though massless and devoid of substance of any kind, this cosmic emptiness reordered the internal workings of his mind around it. That something utterly insubstantial should come to exert its influence over every aspect of the astronaut's life was not surprising to some of the psychiatrists. "It is called 'existential angst'," they explained to the astronaut.

"Is it common on Earth?" he asked.

"Yes, but it is usually found in teenagers, who eventually outgrow it."

|

|

|

|

|

December 31, 2018

A Resolute Ally

Tony owed much of his recent good fortune to an ordained minister of the Episcopalian church, who made a habit of finding work for those who had temporary brushes with homelessness. When she discovered that Tony was a self-described astronaut, she naturally assumed that he possessed technical skills. Swayed by his calm demeanor and quiet words, she took Tony under her wing. Her husband owned and operated a small computer service center, at which Tony became the third technician, and the fifth employee overall, once the minister's husband and the secretary were counted.

Because the technology was so primitive relative to that of his home world, Tony had little difficulty in diagnosing faulty components in the computers that were placed before him, nor in reinstalling operating systems in computers that had become so gummed up with malware and viruses that they no longer functioned. In fact, he was an exemplary employee. And though he was the most efficient of the technicians, he was paid the least, not because he was the most recently hired, but because, unlike the other two, he could not produce an associate's degree in electronics nor any other documentation of credentials in the field.

To compensate for his modest salary, the minister rented to Tony the upstairs apartment unit of a rental home, which she and her husband owned, at a very reduced rate. The family--a wife and two children--of one of the other technicians lived on the first floor. Tony almost never saw them because when he wasn't working at the repair shop, he was combing the streets looking for his wife.

Considering Tony a great success, the minister encouraged him to spend time with her at the city mission, where she interviewed those seeking jobs in an attempt to screen out alcoholics, drug addicts and others destined for or otherwise committed to chronic homelessness. "Perhaps," she had said to Tony, "your wife will turn up at the mission." She thought such a coincidence natural, since, after all, that is where she had found Tony after he had been released from Lake View shortly before its closure.

Although Tony desperately wanted to locate his wife, he hoped that he would not find her in such a place, for it would mean that she too had been seriously damaged in the crash. She was the strong one in their relationship. Internally, he believed that she would find him before he found her, so it was important for him to make himself as visible as possible. Sometimes he contemplated ways to get his face plastered in the papers and on the local television news, in hopes that he might be brought to her attention. He had not yet taken such drastic measures.

"Trust in Jesus," the minister advised him.

Tony had known very little about Jesus before coming under the employ of the minister and her husband. They placed numerous constraints upon their rehabilitated employees. Most of them were eminently reasonable--to keep away from drink and drugs, to show up to work every day, to stay away from previous associates if they had a criminal history--but one point on which they were adamant--to attend the church at which the minister delivered her sermons on a weekly basis--had seemed less essential, at least to Tony.

"I don't know anything about Jesus," Tony had admitted, although he had already been made to understand that Jesus had come to save Earthlings exclusively and then, only one particular species of Earthling.

"If you are to walk as a child of God," the minister instructed him, "you have to let Jesus into your heart."

"Okay," Tony agreed easily enough, reminding himself that when in Rome, one must do as the Romans do.

"Jesus," he prayed as he knelt between pews, "I earnestly beseech you to invoke what powers are available to you in order to aid me in the search for my wife, who is dear to me beyond all others and whom I have, by accident, lost."

In this way, the endeavors of the astronaut became a blessed crusade, sanctioned by God and one of his Earthly ministers. With Jesus counted among his allies, Tony's confidence in the successful resolution of his quest was fortified. This is what is meant when people say that the act of prayer doesn't change God's mind but rather changes the mind of the one making the prayer.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This work is made available to the public, free of charge and on an anonymous basis. However, copyright remains with the author. Reproduction and distribution without the publisher's consent is prohibited. Links to the work should be made to the main page of the novel.

|

|

|

|

|

|