|

|

|

|

The Poison Pie Publishing House presents:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

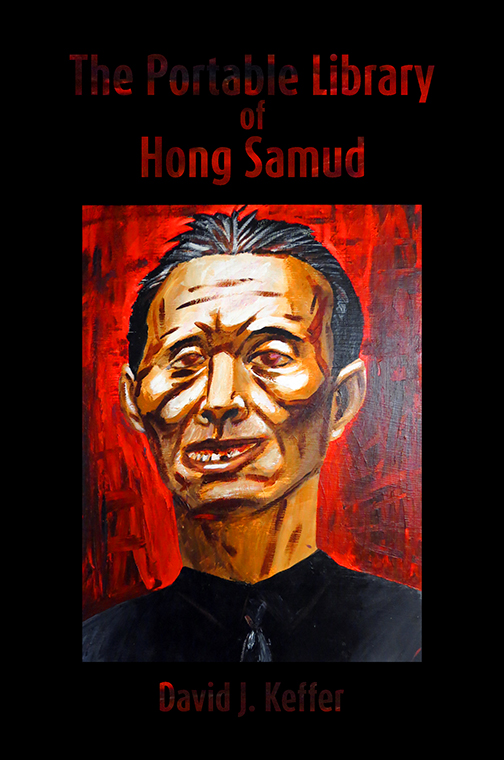

The Portable Library of Hong Samud

(link to main page of novel)

August

|

|

|

|

|

Part One. Hong Samud & the Crow Maiden

|

|

|

August 25, 2015

On the Librarian

As with many of us, the actuality of the world did not meet with Hong Samud’s expectations. He desired to exist in a world with a greater proportion of virtue and a commensurate reduction in vice. The world of course remained intransigent, wholly ignoring his prayers for change as if they were the fanciful wishes of a child dreaming of endless bowls of ice cream.

Many of history’s notable personalities have shared such a sentiment with Hong Samud. In their dissatisfaction at the state of things, heroes of old have taken matters into their own hands, worked within the mechanisms available to them and changed the world, as often for the better as not. Hong Samud, a scholar, was well acquainted with this model in general and many specific examples in particular. He pondered a course of action. That, ultimately, he chose a different path was a consequence of an honest, introspective recognition on his part. He was a contemplative man, who preferred the company of books to that of people. Of homely countenance and diminutive stature, the idea of anyone pledging their allegiance to a crusade under his banner seemed laughable to him.

Rather than sapping his confidence, this admission filled Hong Samud with a renewed sense of purpose. If he could not alter this existing world to a state that better suited him, then he would start from scratch, creating his own world, with meticulous precision, designing it in such a way that the natural outcome of events promoted virtue, recognized and rewarded merit, and nurtured suffering strictly when it led to the growth of wisdom. Pointless suffering or suffering at the hands of an unyielding brutality, willful or otherwise, was to be eliminated entirely.

Hong Samud took leave of his colleagues at the university, whom he knew well enough to accept that they could not aid him in this endeavor. When questioned as to where he was going, he answered truthfully though somewhat ambiguously that he intended to construct a more acceptable world. Some who heard him imagined that he was experiencing a midlife crisis. Others quietly suspected that the quiet, solitary man had finally succumbed to the depression of his self-imposed isolation and planned a discrete suicide. No one thought to interpret his words literally.

Hong Samud wrote patient letters to his sisters and his mother, explaining his departure as a necessary sabbatical that he had postponed far too long. Even though these relatives interacted with Hong Samud only every few years, they remembered his nature, transparent even as a child, well enough to fear, as they read between the lines, that they should not see him again. He was gone by the time their replies, filled with cautionary words, arrived.

Because, as we have mentioned, Hong Samud was a bibliophile, we should not be surprised to discover that he chose to fashion his paradise in the form of a library.

|

|

|

|

|

August 26, 2015

On Creating a Demi-plane

Although he chose to start from scratch, Hong Samud was not at a loss for resources. There were numerous texts for accessing states of mind through which distant realms could be reached. Broadly speaking, these texts fell into three categories. The first set of tomes relied on mental discipline, in which the ascetic devoted himself or herself to a regimen of rigorous training that elevated the mind from the world of dust to a higher level of understanding. There were numerous philosophies established around the world in whose codified practices one might find a means of egress to such a realm.

The second category of tomes also accepted the existence of a multiverse, a likely infinite number of infinitely malleable planes of existence. Included within this scheme were such constructs as parallel universes, alternate realities and, of interest to this work, demi-planes. A demi-plane was typically thought of as a finite, bounded and relatively small universe intentionally created by an individual or a group of like-minded thinkers to fulfill a specific purpose. The most effective means of storing either great wealth (or imprisoning troublemakers) was in a vault (or cell) composed of a demi-plane constructed for just such a purpose then rendered inaccessible among the infinity of realms by inducing those who had created it to forget where they had placed it or even that they had created it all. This process relied on a kind of magic to create a demi-plane followed by subsequent spells to make it permanent and to hide it from various forms of pernicious detection.

The third category of books on the subject of accessing distant realms was of a theological nature. Of course, the distinction between philosophy, magic and theology is often blurred if not arbitrary. Here we rely on convention to distinguish the three. Accessing a paradise or a purgatory or a hell was possible through divine means. Similarly, the creation of an extraplanar sanctuary could be accomplished through the granting of a suitably ardent and well-placed prayer.

There was a fourth category that we have neglected, which was based on a collection of concepts that were commonly referred to as ‘science’. Some elements of science predicted the existence of the alternate universes. Scientists also identified singularities in the fabric of the physics-based reality, which might serve as passageways to alternate realities. However, we say no more on this subject, since the state of science was currently not developed sufficiently to provide instructions on how to access these other planes, much less create one.

Hong Samud, for his part, maintained an academician’s interest in philosophy, magic, theology and science. In fact, much to the dismay of his university colleagues, he lacked the fundamental capability to distinguish between these ostensibly disparate fields. Such a weakness had often gotten him in trouble. However, in the creation of a new world, his stubborn insistence on seeing all aspects of the world as outgrowths of a single, unified concept, proved useful as it allowed him to take what he needed from wherever he could find it, so that the realization of his library could come to fruition.

|

|

|

|

|

August 27, 2015

On the Architectural Layout of the Library

Hong Samud appreciated equally symmetry and the breaking of symmetry. The architectural design of his library reflected this ambivalence. The library was composed of individual rooms placed on both sides of a central hallway. The rooms themselves were uniformly square in shape with sides of forty feet. This dimension was a consequence of the admittedly limited ability of Hong Samud to create something out of nothing. The doorways (entirely absent of doors themselves) to rooms lying on far sides of the hall were placed exactly opposite each other.

Rather than extending in a straight line, the hallway curved in such a way that the pairs of rooms appeared at the four principal points of a compass. However, the circuit was not closed, for if one traveled past four pairs of rooms, they did not arrive at the point where they had started. Instead, one arrived at a fifth room. Curiously, if one traveled clockwise one full revolution around the hall, one a discovered a different room than if one, starting at the same point, traveled counter-clockwise.

A reader inclined to geometry may quickly identify this spatial arrangement as a spiral of constant radius extending along a direction perpendicular to the plane of the circle. This is a reasonable interpretation of the layout of the library save in one respect. There was no perceptible slope in the central hall. Traveling clockwise felt no more like climbing up a slope than traveling counter-clockwise did descending. In fact, if one scattered a handful of glass marbles on the stone tiles of the floor, one would have found they revealed no persistent incline whatsoever.

Such are the rules of demi-planes. The geometry of our physics-based reality may not wholly apply. If the fundamental truths of mathematics can be flouted in such a place, one can well imagine that other seemingly more arbitrary constructs, for example an ethical value system, may lie in even greater jeopardy.

|

|

|

|

|

August 28, 2015

On the Contents of the Library

Hong Samud brought every book he had ever read, in part or in whole, into the library. Such indiscriminate behavior on the part of the individual in charge of collection acquisitions would not be tolerated in a traditional library, where the funds to acquire texts as well as the space to store them were at a premium. However, such constraints did not face Hong Samud for when the first book was placed in the last available room, another segment of the spiral appeared, providing eight additional rooms. This was no accident; the library possessed the potential for an infinite capacity by design.

Setting aside practical concerns regarding finite resources, one might yet expect our librarian to exercise some measure of discretion in the selection of the material that filled his library for other reasons. After all, it was his explicit purpose to create a new world in which the preponderance of joy dwarfed suffering. Surely, there were texts which focused overmuch on topics not conducive to this purpose. Hong Samud recognized this dilemma but was not troubled by it, for he prized knowledge in all its forms. Books of photography that captured the horrors of the battlefield in terms of ghastly piles of amputated limbs behind the makeshift medic’s tent were unlikely to bring anyone joy. Similarly, documentaries, which catalogued a ruthless accounting of genocide, or tomes of the occult, which described grisly rituals for the express purpose of inviting darkness into the world might have been omitted by a more prudent librarian. However, Hong Samud left nothing out.

If we sit quietly and wonder to ourselves as to the motivations behind his overly inclusive policy, we are ultimately charged with attempting to imagine a process by which these books of nightmares, real and imagined, could make a new world a better place. The only answer, though Hong Samud himself would never admit it, was that he saw no alternative but to place his trust in the informed judgment of those who would come to occupy this new world. He had yet to consciously admit this fact, which was why, for the first thousand years, Hong Samud kept the library to himself.

|

|

|

|

|

August 31, 2015

On the Librarian’s Favorite Books

These books were like children to Hong Samud, who had neither married nor sired human children out of wedlock. As such, asking him to choose a favorite one was an indiscreet question. Nevertheless, we shall say a few words on this delicate subject.

Hong Samud particularly loved bestiaries. A bestiary is, of course, a catalogue or an encyclopedia of creatures, preferably illustrated though some notable bestiaries have appeared in text only. In such books, Hong Samud allowed his imagination to run wild. Many beasts that he should never otherwise see he discovered and explored as if he had silently, invisibly invaded their lair and watched as they performed the idiosyncratic habits of their species. It made little difference to Hong Samud whether the unlikely creatures could be found in a physics-based reality, like the platypus or aye-aye, or had been real but succumbed to extinction, like the thylacene or the triceratops, or had yet to be produced by the whimsical (often cruelly so) process of evolution, like the three-eyed dog or the perfect husband. Bestiaries devoted to mythical creatures—unicorns and dragons and their ilk—Hong Samud also found perfectly acceptable.

Hong Samud no less felt a particular predisposition to cosmological atlases. Again catalogues of a kind, these tomes investigated the arrangement of stars and the peculiar geologies of the planets that orbited them. Speculative works on the subject of hidden systems located within the clouds of nebulae also excitedly provoked his imagination. He even enjoyed perusing monographs written by physical scientists describing the unusual dynamical processes that took place under bizarre, celestial conditions, though he was not always able to follow the complex and abstract mathematics that filled such texts. Philosophical works in which schema were presented arguing that the four-dimensional physics-based reality was in fact a lower-order projection of a higher-dimensional reality cast upon the curtain of some cosmological object, like a black hole, also appealed greatly to the sensibilities of Hong Samud.

Although he was no scholar of the social sciences, Hong Samud possessed a secret vice for the works of economists. He found in their mingling of mathematical principles describing the evolution of economic processes and their concern for the social welfare of those engaged in such activities a mesmerizing puzzle. He found that no authors more strongly condemned the vices of humanity than economists who unequivocally documented, through the careful analysis of data, historical patterns by a wealthy elite of subjugation of the lower classes based more or less exclusively upon the principle of self-interest of few, opportunistic individuals. He admired such economists for he lacked both the education and the courage to make such dramatic statements himself. Hong Samud found no books as emotionally compelling as economic treatises in which the sympathy of the author for those, made vulnerable by circumstance and poor judgment, escaped between the otherwise rigid and academic lines of text. During the reading of such a book, Hong Samud often had to set it down to dry his eyes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This work is made available to the public, free of charge and on an anonymous basis. However, copyright remains with the author. Reproduction and distribution without the publisher's consent is prohibited. Links to the work should be made to the main page of the novel.

|

|

|

|

|

|