|

|

|

|

Music Reviews from the Staff of the Poison Pie Publishing House

|

|

April 17, 2017

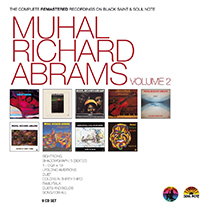

A Second Volume of Collected Muhal Richard Abrams

This boxed set flew under our radar. It was released in November, 2016 but we didn't hear about it until spring, 2017, which is why we are only reviewing it now. First, a bit of context: Black Saint and Soul Note records were two Italian labels (founded by Giacomo Pelliciotti in 1975, owned by Giovanni Bonandrini since 1977 and acquired by CAM Jazz in 2008) that released jazz and free jazz recordings. The catalogs include a prestigious list of hundreds of artists, including Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, Steve Lacy, to name but a few. Predominately featured in the catalog are many artists of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), including Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell, Henry Threadgill, Lester Bowie, George Lewis, Amina Claudine Myers, Anthony Braxton and many more.

This boxed set flew under our radar. It was released in November, 2016 but we didn't hear about it until spring, 2017, which is why we are only reviewing it now. First, a bit of context: Black Saint and Soul Note records were two Italian labels (founded by Giacomo Pelliciotti in 1975, owned by Giovanni Bonandrini since 1977 and acquired by CAM Jazz in 2008) that released jazz and free jazz recordings. The catalogs include a prestigious list of hundreds of artists, including Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra, Steve Lacy, to name but a few. Predominately featured in the catalog are many artists of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), including Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell, Henry Threadgill, Lester Bowie, George Lewis, Amina Claudine Myers, Anthony Braxton and many more.

Beginning with Charlie Haden in 2010, Cam Jazz began to reissue remastered recordings from the Black Saint and Soul Note catalog as compact discs in boxed sets. Today there are nearly fifty such boxes. In 2012, a first collection (Volume 1) of Abrams recordings was released, containing eight discs in which Abrams was the featured artist in the ensemble:

- Spihumonesty (Black Saint, 120032-2, 1980, cd)

- Mama and Daddy (Black Saint, 120041-2, 1980, cd)

- Blues Forever (Black Saint, 120061-2, 1982, cd)

- Rejoicing with the Light (Black Saint, 120071-2, 1983, cd)

- View from Within (Black Saint, 120081-2, 1985, cd)

- The Hearinga Suite (Black Saint, 120103-2, 1989, cd)

- Blu Blu Blu (Black Saint, 120117-2, 1991, cd)

- Think All, Focus One (Black Saint, 120141-2, 1995, cd)

The recently released Volume 2 contains nine discs, featuring nine different ensembles, in some of which Abrams appears as a sideman.

- Sightsong (Black Saint, BSR 0003, 1976, cd)

- Shadowgraph (Black Saint, 120016-2, 1978, cd)

- 1 - OQA + 19 (Black Saint, BSR 0017, 1978, cd)

- Lifelong Ambitions (Black Saint, BSR 0033, 1981, cd)

- Duet (Black Saint, BSR 0051, 1980, cd)

- Colors in Thirty-Third (Black Saint, BSR 0091, 1987, cd)

- Familytalk (Black Saint, 120132-2, 1993, cd)

- Duets and Solos (Black Saint, 120133-2, 1993, cd)

- Song for All (Black Saint, 120161-2, 1997, cd)

These discs highlight the collaborative philosophy of the AACM musicians, described in George Lewis' book, A Power Stronger than Itself, in which musicians readily agreed to appear on each other's records. For example, Shadowgraph is a George Lewis record. Only Lewis' name appears on the cover and the disc was previously collected in Lewis' Black Saint/Soul Note box set. In Duets and Solos, Roscoe Mitchell gets first billing; this disc also was previously collected in Mitchell's Black Saint/Soul Note box set. Lifelong Ambitions has Leroy Jenkins as the headliner. In others, like Duet with Amina Claudine Myers, or Sightsong with Malachi Favors, Abrams is the highlighted musician, presumably for marketing purposes since the music sounds very much a collaboration among equals. The most star-studded line-up is on 1-OQA+19, which headlines Abrams in an ensemble with Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill, Steve McCall and Leonard Jones.

These nine discs span the years from 1976 to 1997. Those us who were alive during that span of 21 years can each think of some ways in which the world significantly changed (e.g. the propagation of computers into every day life) and other ways in which the world stayed the same (e.g. the truculence of human nature). In any case, as others have noted, much of this music was never assimilated into the popular culture. It remains a music produced in the cultural margin and largely relegated to that status. That sufficient interest in the cultural margin exists to prompt the commercial reissue of many boxes of such fare is, perhaps, an indication of the (partial, of course) splintering of a monolithic culture, prompted by such things as (i) a growing recognition of the inadequacy of paragons of the monolith in representing the distribution within a culture and (ii) technological advances that allow disparate but like-minded individuals to access the work of artists of the cultural margin. One no longer has to live in one of a handful of cosmopolitan urban centers to be exposed to the artists who previously could only find a critical mass of appreciation to sustain their work in such places.

Terrifically different music appears on each of these cds, with the only common thread being the presence of Abrams on piano (on all nine discs), synthesizer (1-OQA+19, Familytalk and Song for All) and voice (1-OQA+19). Each of these releases possesses their own distinct appeal. Here, we do not exhaustively review each individual release. Rather, we mention some personal highlights.

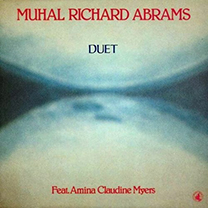

Duet (1980) features two pianos played by Abrams and Amina Claudine Myers. In listening to this music, it is useful to consider the following quote from Myers.

With Muhal it was totally open, once you got past the reading part. Henry Threadgill's music is hard, and Roscoe's [Mitchell] and Leo's [Smith]. [Anthony] Braxton, his stuff looks hard, but you just have to keep up with the time span. I found that with Leo too. He has some tricky stuff, so you have to keep up. They go for the overall sound. This is what I tell my musicians now--this is just a feeling, don't worry about the music. The music is a guide; just do your thing. The charts Muhal wrote for the AACM--I was inexperienced, in from the country (laughter), and his music seemed hard. You had to practice.*

With Muhal it was totally open, once you got past the reading part. Henry Threadgill's music is hard, and Roscoe's [Mitchell] and Leo's [Smith]. [Anthony] Braxton, his stuff looks hard, but you just have to keep up with the time span. I found that with Leo too. He has some tricky stuff, so you have to keep up. They go for the overall sound. This is what I tell my musicians now--this is just a feeling, don't worry about the music. The music is a guide; just do your thing. The charts Muhal wrote for the AACM--I was inexperienced, in from the country (laughter), and his music seemed hard. You had to practice.*

After a (pleasantly) anomalous first track, in Duet, you hear Abrams being Abrams on the piano and Myers playing a complementary role. But her presence is felt in the playing, which at times unabashedly takes on a more idiomatic tone, sometimes with hints of ragtime, sometimes gospel. Of course, most of the time, there is a complex interplay between the two pianists engaged in a joint venture of "creative music".

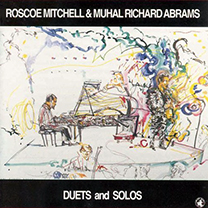

Duets and Solos (1993) features Abrams on piano and Roscoe Mitchell on saxophone, with a solo from each and two duets. As we noted in our review of the Roscoe Mitchell: The Complete Remastered Recordings on Black Saint & Soul Note boxed set, this disc "presents unpredictable and more than compelling--engrossing--music that has absolutely no relation to anything one would associate with the traditions and trends of 1993. As if this music was created outside time and space, it still sounds very much a music of the moment because it did not incorporate sounds of the day that have subsequently become dated." The appeal of Duets and Solos is not limited to the duets. The Abrams piano solo, Scenes and Color runs over 26 minutes in length. For those who have always associated piano solos with classical music, in which the pianist is expected to execute the will of the composer with technical fidelity, this piece is an eye-opener. The music is simultaneously sonically beautiful, intellectually stimulating and esthetically appealing. It can change how one thinks about solo piano music. It opened my appetite for things like Vijay Iyer's album, Solo.

Duets and Solos (1993) features Abrams on piano and Roscoe Mitchell on saxophone, with a solo from each and two duets. As we noted in our review of the Roscoe Mitchell: The Complete Remastered Recordings on Black Saint & Soul Note boxed set, this disc "presents unpredictable and more than compelling--engrossing--music that has absolutely no relation to anything one would associate with the traditions and trends of 1993. As if this music was created outside time and space, it still sounds very much a music of the moment because it did not incorporate sounds of the day that have subsequently become dated." The appeal of Duets and Solos is not limited to the duets. The Abrams piano solo, Scenes and Color runs over 26 minutes in length. For those who have always associated piano solos with classical music, in which the pianist is expected to execute the will of the composer with technical fidelity, this piece is an eye-opener. The music is simultaneously sonically beautiful, intellectually stimulating and esthetically appealing. It can change how one thinks about solo piano music. It opened my appetite for things like Vijay Iyer's album, Solo.

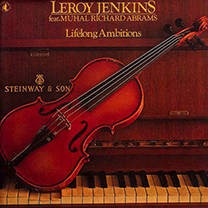

Lifelong Ambitions (1981) presents a violin (Leroy Jenkins) and piano (Muhal Richard Abrams) duet unlike anything that came before or likely since. To call these pieces "jazz" is not very informative and would only be done in reference to the musicians who created the music. To call these pieces "contemporary classical" is also inaccurate and references only the traditional roles of the instruments, since the creative process is clearly dominated by improvisation rather than composition. Of course, the appropriate term is that originally adopted by the AACM, creative music, which is intentionally ambiguous and allows plenty of lattitude. The appelation favored by the staff of the Poison Pie Publishing House, non-idiomatic improvisation, is also appropriate. Those who argue that non-idiomatic improvisation is an oxymoron because, for example, the AACM 'tradition' of creative music has established its own idiom, should listen to this album again. This music contributed to no idiom.

Lifelong Ambitions (1981) presents a violin (Leroy Jenkins) and piano (Muhal Richard Abrams) duet unlike anything that came before or likely since. To call these pieces "jazz" is not very informative and would only be done in reference to the musicians who created the music. To call these pieces "contemporary classical" is also inaccurate and references only the traditional roles of the instruments, since the creative process is clearly dominated by improvisation rather than composition. Of course, the appropriate term is that originally adopted by the AACM, creative music, which is intentionally ambiguous and allows plenty of lattitude. The appelation favored by the staff of the Poison Pie Publishing House, non-idiomatic improvisation, is also appropriate. Those who argue that non-idiomatic improvisation is an oxymoron because, for example, the AACM 'tradition' of creative music has established its own idiom, should listen to this album again. This music contributed to no idiom.

Shadowgraph (1978) is another example of George Lewis as an experimental musician. His discography is not filled with a characteristic sound, unlike that of, for example, Derek Bailey. His improvisational computer experiments with Voyager (1993), his "European-Free-Improvisation" styled Conversations (1998) with Bertram Turetzy, his openly jazz News for Lulu (1988) with John Zorn and Bill Frisell, or his Solo Trombone Record (1977) not one of these is like the other. Nor are any of them like Shadowgraph. That a single individual can create according to many different aesthetic principles is, one supposes, the mark of either a genuine experimentalist or a man with no intrinsic principles of his own. Never has being unprincipled sounded so appealing! In any case Shadowgraph contains four group improvisations (with Abrams appearing on piano on two of the four tracks) structured around some predetermined guides "composed by" Lewis. Of his records in this vein, Homage to Charles Parker (1979) is a personal favorite.

Shadowgraph (1978) is another example of George Lewis as an experimental musician. His discography is not filled with a characteristic sound, unlike that of, for example, Derek Bailey. His improvisational computer experiments with Voyager (1993), his "European-Free-Improvisation" styled Conversations (1998) with Bertram Turetzy, his openly jazz News for Lulu (1988) with John Zorn and Bill Frisell, or his Solo Trombone Record (1977) not one of these is like the other. Nor are any of them like Shadowgraph. That a single individual can create according to many different aesthetic principles is, one supposes, the mark of either a genuine experimentalist or a man with no intrinsic principles of his own. Never has being unprincipled sounded so appealing! In any case Shadowgraph contains four group improvisations (with Abrams appearing on piano on two of the four tracks) structured around some predetermined guides "composed by" Lewis. Of his records in this vein, Homage to Charles Parker (1979) is a personal favorite.

1-OQA+19 (1978) seems to the ear of this listener to be a light-hearted recording of a session in which a group of five musicians (Abrams, Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill, Steve McCall and Leonard Jones), long known to each other, came together to have fun. No matter how many golden records are flung into interstellar space, one can rest assured that this music will never be on one. It's music of the moment with titles like Arhythm Songy intended to be heard during the ephemeral lives of Earthlings only. Even among Earthlings, the music is, as often as not, probably sorely misunderstood.

1-OQA+19 (1978) seems to the ear of this listener to be a light-hearted recording of a session in which a group of five musicians (Abrams, Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill, Steve McCall and Leonard Jones), long known to each other, came together to have fun. No matter how many golden records are flung into interstellar space, one can rest assured that this music will never be on one. It's music of the moment with titles like Arhythm Songy intended to be heard during the ephemeral lives of Earthlings only. Even among Earthlings, the music is, as often as not, probably sorely misunderstood.

There is no questioning the important role that Black Saint and Soul Note played in providing a venue for musicians of the AACM to present their music. Today, we also recognize the importance of the historical document that the recordings on Black Saint and Soul Note represent. One thing that idly crosses my mind is that, in reading interviews and liner notes, I have not come across anyone who claims that their favorite record by artist X is on Black Saint or Soul Note. For musicians like Cecil Taylor, Steve Lacy and others, the seminal recordings are always identified on other labels. Is there any artist for whom a general consensus exists that one of his/her best records came out on Black Saint or Soul Note? If so, it might be Muhal Richard Abrams and the album is collected in one of these two boxed sets. As for a favorite, it is impossible to choose.

For those pondering the question, "Which of the two Muhal Richard Abrams Black Saint boxes should I buy first?", the answer is clearly, "You can't go wrong with either one of them." Volume 2 showcases Abrams as both headliner and sideman, and for that additional element of diversity of ensembles, I lean toward recommending Volume 2, but that opinion is not written in stone. If i were asked tomorrow, I might recommend the excellent Volume 1 first.

* Amina Claudine Myers, interview with George Lewis, Bomb Magazine, Vol 97, Fall 2006.

|

|

more music reviews

|

|

|

|

|