|

|

|

|

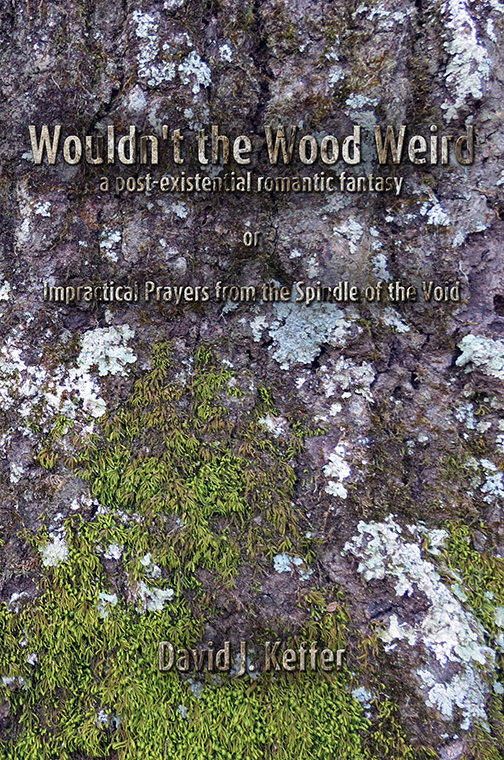

The Poison Pie Publishing House presents:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wouldn't the Wood Weird

a post-existential romantic fantasy

or

Impractical Prayers from the Spindle of the Void

(link to main page of novel)

January

|

|

|

|

|

January 4, 2018

The Fortune Teller

Having laid out the four cards in a horizontal row, the fortune teller methodically revealed each one in turn, from the left to the right of the woman sitting across the table from her. First, she revealed 'The Tree'. The image on the well-worn card was not of a tree in the full bloom of spring but rather a leafless skeleton of winter. "It means 'judgment'," said the fortune teller.

The woman nodded in understanding, although she had already known the significance of the card.

The second card to be turned over was 'The Witch'. This card depicted a woman's face surrounded by a starry field in which the constellations did not correspond to those in a familiar sky, instead bearing amorphous shapes of leaves, rivers and flames. "It means 'tragedy'," said the fortune teller. She glanced up to observe the reaction in the woman's face but discerned nothing. "All evil things, including black witchcraft, have an origin in tragedy," she added by way of justifying her interpretation of the card. This additional comment too drew no response from the woman whose fortune she foretold.

The third card revealed 'The Spirit'. The surface of this card bore almost no ink. Only a faint silhouette of an androgynous form, walking with one arm extended as if pushing aside a curtain, was traced on its surface. "Ordinarily," said the fortune teller, "'The Spirit' is an auspicious omen, a prediction of divine intercession. However, in this sequence, following 'The Tree' and 'The Witch', its meaning is ambiguous."

The fortune teller shrugged apologetically and flipped over the fourth and final card of the reading, 'The Traveler'. The Traveler carried a bag slung of his shoulder and a walking staff in one hand. Upon his face rested a serene expression. The fortune teller studied the cards as a whole before she spoke again. "You were on a journey," she said to the woman. "You have lost your traveling companion." There was a certain tentativeness in the voice of the fortune teller. She waited for confirmation from the woman but none was forthcoming.

Instead, the woman seated across from the fortune teller extended her hands and, placing them one on each card, flipped them over so that they lay face down again. She had her own interpretation of the cards, which she would not share with the fortune teller. The tree, the witch, the spirit...in his fall to Earth he had taken up company with only those willing to accept him. The woman could hardly blame him for his weakness, for she felt it too.

|

|

|

|

|

January 5, 2018

The Tiger Trap

"We could make a tiger trap," Ohu said to Samudra, as the two women sat on the cold ground beneath the outstretched arms of Wouldn't. "When Tony comes to visit you, he would fall in and we'd have him!" She looked up at the tree. "When do you think he'll stop by?"

Wouldn't replied, "It's hard to say. He keeps an erratic schedule."

"Excuse me," said Samudra, unwrapping her arms from around her knees. She had been bundled up to ward against the chill wind. "Did you say tiger trap?"

"It's a pit," Ohu said, "the kind that people catch tigers with...in the lands where tigers roam...India?" She ended her statement questioningly because, although she did not know exactly where Samudra had been born, she felt it likely in that part of the world.

"Aren't tiger pits full of sharpened stakes at the bottom?" Samudra asked, pointing out what she felt was a rather obvious flaw in the plan for they had, as far as she knew, no intention of skewering Tony.

"Hmm," Ohu said. "You might be right. A tiger trap with no stakes is what I was talking about."

"A pit," Samudra clarified. "And what about the hundred other pedestrians and joggers and kids that run by Wouldn't and fall in the pit before Tony shows up?"

"So many tigers!" Ohu exclaimed. She looked over her shoulder, perhaps to see if one was sneaking up on her as they spoke.

Wouldn't spoke then in a calm, reassuring voice. "There is no need for a pit. When Tony comes, I will set up a meeting with the four of us. Once I get him to agree to that meeting, he will certainly return; he is a man who honors his obligations."

"I don't know how he is going to help us. What do you see in him?" Samudra said, finally voicing the doubt that had been the purpose in her coming.

"No, Samudra," said the tree. "You misunderstand me. It's not what we see in him. It's what he sees in us that will make the world a better place."

|

|

|

|

|

January 7, 2018

A Prayer for Trees Who Were Once People

O Lord, I come to you today with a prayer

for conifers, armored in needles and armed

with a frugality worthy of a miser, for they

know the cold to come and how best to bear it.

I ask also that you look kindly upon oaks,

maples and other deciduous residents

of temperate forests, who, expanding

in seasonal rings, respond to your natural laws.

O Lord, forget not the arboreal denizens

of the rain forest, in which, beneath a canopy

of leaf, a frantic struggle for each wayward

fragment of sliding sunlight is daily waged.

Finally, O Lord, grant peace to solitary trees,

arising alone in fields and pastures, for they

were once men, who finding the company

of their own too much to bear, imagined a heaven

in the form of a tree, forgetting, intentionally

I suspect, that the absence of other forms implied

a sentience, which manifested in majesty only

at the expense of countless, unrealized alternatives.

|

|

|

|

|

January 8, 2018

A Reluctant Acquiescence

"Wōden der Udwyrd," said the astronaut in greeting, "I hope I find you well."

"Mitätön Kara," replied the tree, "I have been awaiting your visit."

The astronaut laughed softly, the darkness concealing his expression. "You need not attempt to flatter me. I know the extent of my insignificance."

The tree ignored the reply and immediately set to explaining to the astronaut his plan to form a coalition of like-minded individuals with the simple intention of making the world a better place. We need not remind the reader of the inherent contradiction in the plan since the tree implicitly distrusted human institutions. Perhaps since his plans involved a tree, an astronaut of extraterrestrial origin, a woman already drowned and a psychic deeply linked to the spiritual world, he considered his proposed coalition beyond the human condition.

Despite the plentiful opportunity for ambiguity, the astronaut quickly sensed where this conversation was headed and grew dismayed; he had only come to the park for a few moments of companionship to assuage his loneliness. "There are already many such organizations," he said, thinking of his own benefactors.

"Some duplication of effort in this regard is not necessarily a flaw," answered the tree.

Above them a crescent moon hung in the night sky, one sliver bright and the remaining portion dark but a shade paler than the blackness surrounding it. The hour of the curfew for the park had long since passed, but the astronaut did not heed these restrictions, knowing as he did that whatever illicit activities the curfew had been adopted to prevent were ones in which he had no intention of engaging.

"Will you join us?" asked the tree.

"Who is us?"

"Myself, Samudra, Ohu. You would make our trio a quartet."

At this time, the astronaut did not reveal to the tree that he had recently aligned himself with Jesus. He was not sure whether the divine presence would necessitate relabeling the group as a quintet. In any event, the astronaut knew both women well from his time in Lake View. "You already have a capable team. I don't have anything to add."

"On the contrary," said the tree, "We need you." He said this last statement with utter conviction.

"I'm occupied now," protested the astronaut, who in truth did not want to devote time to anything not directly related to the search for his wife. He already spent forty hours each week repairing computers, a deviation of resources made necessary by the circumstances in which he found himself without external support.

"We can help you find her," said the tree. "That would be our first task."

The astronaut remained standing several feet from the trunk. At the border of the park, a car sped by, the hum of its engine rising in approach then falling as it receded. He looked for words to decline the offer but couldn't find a good reason other than he feared the hopelessness of his search and he did not desire to share his eventual failure with anyone but himself. This truth he was unwilling to vocalize, even to the tree, whom he could have trusted to keep his secret.

The tree, for his part, received this message based on a hundred intimations that emerged from the astronaut's stance, the tone of the words delivered before and after, the silence that momentarily consumed him, and the way the moonlight struck his bald scalp.

"What shall I say?" asked the astronaut. He had no desire to disappoint this tree.

"Okay would be enough," said the tree encouragingly.

"Okay," repeated the astronaut in a voice that revealed his misgivings.

The tree left not a moment for the astronaut to retract his statement nor to impose conditions on his agreement. Instead, the tree immediately asked, "Where are you, currently, in your investigation?"

"Mostly wandering around town uselessly," admitted the astronaut. In truth, he had begun to haunt the same locales with such frequency that he was afraid people, especially local police officers, were beginning to recognize him. If they asked him about his business, he had no answer prepared, for he feared that telling the truth would return him to Lake View, resulting in a disruption in his search that he could not tolerate.

"Perhaps, it would be helpful if we revisited the crash site," suggested the tree.

|

|

|

|

|

January 11, 2018

A Picnic

"Don't wreck it," Samudra said as she reluctantly handed the keys of her car to Ohu. It wasn't a particularly expensive car, a five-year-old four-door sedan, but it had the advantages of being paid off and functioning reliably.

"If you are so worried about my driving," Ohu replied, "you could always come with us. It's not like you have some terribly pressing business to take care of on a Saturday."

"No," agreed Samudra, "it's exactly that. I have nothing to do on this Saturday and I won't let Wouldn't's crazy plans change it. I am going back inside," she pointed to the front door of her house, "and I am going to crawl back in bed and not get up until two!" She spun away and marched to the door, pausing with it half way open to shout over her shoulder, "Don't wreck it!"

Ohu examined the silvery car for a moment. She had neglected to confide to Samudra, after she had gone to the trouble to pick her up, that it had been some years since she had last driven a vehicle of any kind. She took an exaggerated breath and hopped in the car.

She drove for nearly a minute before she realized that the beeping sound was the car's attempt to bring her attention to the fact that she had forgotten to buckle her seat belt. When she pulled up to the address that Wouldn't had provided, she found a modest, two story house in a neighborhood filled with such houses arrange on a compact grid of lots.

The astronaut was waiting in the driveway for her.

He entered the car through the passenger door.

"Tony! Long time no see." In fact, Ohu had not spoken to the astronaut since he had been discharged from Lake View, several months before she had been released.

"Ohu," replied the astronaut, in greeting.

"Would you like to drive?" she asked.

He shook his head. "Whose car is this?"

"Samudra's."

"Where is Samudra?"

"She was busy."

"Do you know how to get to the new Lake View?"

"No," admitted Ohu, who had not planned that far ahead. As was her wont, she happily relied on the actions of others to make up for her carefree approach to life. In this case, she had nothing to worry about, because the astronaut had come prepared with directions to the rural location.

Three-quarters of an hour elapsed as they left the city, during which Ohu spoke much and the astronaut very little. He reassured himself that the worst that could happen was that he had wasted part of a Saturday morning.

"What is your wife like?" Ohu asked him.

The question startled the astronaut, though it seemed eminently reasonable that those who sought to aid him in his search should be privy to such mundane information as the physical appearance of their quarry.

Seeing that her question put her companion on edge, Ohu quickly asked, "Does she have long hair?"

"No," said her passenger. "Astronauts, when they have hair, keep it cropped short so it doesn't get in the way." He pictured her spinning weightlessly in the capsule beside him.

"What color are her eyes?"

"They are green," the astronaut admitted in a wistful voice.

"Does she have four arms like you used to have before the crash?" Ohu asked this as if it were the most natural thing to ask in the world.

"The last time I saw her," said the astronaut, "she still had all four of her arms." He looked at Ohu. "I hope she still does." He did not wish to share his misfortune with his wife.

When they arrived at the modern facility they found it unlike the old Lake View in virtually every aspect. Where the former building had a stately, stone exterior, this building was brick and metal and glass. Where the Lake View they had known was surrounded by trees a century or more in age, a dozen saplings had been planted around this new facility, in a field of sod, much of which would not survive the winter. The view of this uninviting, antiseptic building filled the two visitors with dismay for those patients who now called it home.

"Oh," said Ohu, aghast. "I am glad that Samudra did not come with us. She would be drowning herself right now."

The astronaut was more stoic in his reaction, nodding only in silent agreement.

He had come prepared with all of the necessary paperwork to prove his identity and to retrieve copies of the document associated with his admission. He needed these because he could not remember anything of the crash. They would have to work their way, like a detective, backward along the trajectory he had followed since then.

The papers they received from the business-like clerk at the new Lake View, identified the hospital that had treated his physical injuries, before transferring him to Lake View so that his psychological injuries could be addressed. With these papers in hand, they quickly exited the facility. Neither had any inclination to wax nostalgic over a place that shared nothing in common, save a name, with an institution, of which they harbored fond memories.

The psychic and the astronaut stood in the chill Saturday morning air. "I see my breath," said Ohu.

"Shall we go to the hospital?"

In fact, the hospital was located in another county. It provided some clue that the crash had not occurred near the city. In this rural country, there were modest hospitals to serve the population in the surrounding counties, but only a single government mental facility located in the largest metropolitan area, which served more or less as an unofficial, regional capital.

As a consequence, the astronaut did not know how to get to the remote hospital. Although he felt a great urgency in the search to find his wife, he simultaneously experienced an exhaustion at the enormity of the task before him. There would be many links in the chain of clues that led to the crash site, which itself was only a place that his wife had presumably left, as he had, many months before. Cowed by such prospects, he told himself that he had to shepherd his strength for the long haul. He said to Ohu, "We have made enough progress for one day."

"Great!" she said. "I've been out here before. There's a county park with a waterfall, where the water flows down a slope of rocks that looks like an old man's face and the water is split into a thousand little streams that look like his stringy, white hair." Her face became animated by a memory attached to some former visit to this park. "We'll have a picnic!"

Ohu stopped by a country, grocery store where she bought a loaf of bread from the bakery, a block of cheese, and two apples. They bought nothing to drink for Ohu had spied a bottle of cheap chardonnay in the back seat of Samudra's car. Ohu got them lost twice on back county roads before she found the park, largely by accident. It was well past noon therefore (when Samudra was just getting out of bed) that the astronaut and the psychic sat together at a worn picnic table placed downstream of the falls. The astronaut carved cheese from the block and managed to extract the cork from the bottle, both with his pocket knife.

"Tony," exclaimed the psychic, living in the moment, "we are going to find your wife! I have a good feeling about it!"

|

|

|

|

|

January 12, 2018

A Sermon

At the service on the following day, the minister read from the Gospel of Matthew his exhortation against worry. Her voice rang above the congregation. "Look at the birds of the air, that they do not sow, nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not worth much more than they? And who of you by being worried can add a single hour to his life?"† Her sermon that followed expanded upon this theme, taking examples of causes of needless anxiety in modern life--worrying about the fidelity of one's spouse, the quality of one's children's school, or the elusive promotion at work. In each case, she encouraged her flock to do what they were able on their own and trust in God to carry them the rest of the way.

As the astronaut sat in the wooden pew, he reflected on his newfound enjoyment of the Gospels. In principle, he appreciated any text capable of distributing wisdom and he now counted the Bible among such books. Certainly, the message of this particular passage--not to waste time and energy on anxieties--was a worthwhile message. However, the astronaut failed to be comforted by the admonition to look to the birds. He thought of birds as brute creatures, subject to the whims of the weather and the men who harvested and developed the woodlands in which they once sheltered. Should two birds fail to find sufficient seed to sustain them through the winter, the mated pair might yet express a nobility in their shared suffering, but the astronaut thought a little pro-active planning on their part, a practical manifestation of worry, which served to avoid or at least minimize hardship, would have served them well.

Nor did the minister's sermon resonate with the astronaut, for he worried only for the well-being of his wife. There had been no words of comfort forthcoming for one like him who had lost his wife in a crash and who had to pretend to all but a small circle of friends that she did not exist lest they accuse him of madness. The astronaut tried to formulate a prayer for birds, then a prayer for madness, then a prayer for ministers who failed to awaken their congregation. He succeeded in none of these efforts. He asked Jesus to forgive him for being unable to pray and left the church.

He found Ohu waiting in Samudra's car in the parking lot.

"Do you have the directions?" she asked.

"I do," the astronaut answered. He had looked up the route to the hospital on the previous day. "It's ninety minutes each way," he told her.

"Then we better hurry," Ohu said, because Samudra said she wants her car back by four."

The astronaut looked at his watch, a cheap plastic band with a digital readout. They had five hours. "Okay."

†Matthew 6:26-27

|

|

|

|

|

January 13, 2018

A Revelation

As they drove north, they found the countryside full of the forlorn loveliness of winter. It was a hilly country and the pastures sloped up away from the county road, revealing, as they did so, patches of yellowed grass, and clumps of snow gathered along the north shadows of copses of Virginia pines. The fields lay fallow but the patterns of the ordered rows of crops could yet be seen in the fragmented lines of snow that resisted the sun overhead.

As she drove, Ohu recalled the picnic from the day before. She recalled the warmth of the wine as she and the astronaut had shivered side-by-side on the wooden bench. It was, perhaps, a combination of that memory and the pastoral scenery through which they now traveled that invited Ohu into a contemplative reverie. Her eyes focused on the road. She turned along streets according to the navigational commands of her passenger, but her mind was far away.

Although they were yet early in their search for the astronaut's wife, she had already become enamored with a peculiar idea. Of course, she wanted the astronaut's happiness. Wouldn't had requested her help to make the world a better place and the well-being, even of an astronaut, would shift the balance in favor of joy. The only practical problem with this plan, at least from Ohu's point of view, was her unyielding conviction that the astronaut's wife did not exist. His spouse was merely a figment of his imagination, a mechanism used to cope with the damage he had sustained in the accident. The residents of Lake View had plenty of familiarity with such responses. Ohu had not arrived at this conclusion on her own. On the contrary, in her role as psychic, this message had been delivered by an incorporeal courier from beyond the mortal realm.

One, possessed of less imagination than a psychic, might presume that a search for a wife who did not exist was doomed to failure. Ohu, for her part, espied the inevitable solution. Through this investigation, the astronaut would find his wife--just not the one he had been looking for. He would find a real wife, one who existed in this physics-based reality. This wife would, of course, take the form of Ohu. Who else could it be?

She would travel beside him along each step of their journey. A bond of friendship would form between them; in fact such camaraderie was already beginning to bloom. When their investigation let them to their ultimate destination, some indefinite point at which the astronaut was forced to accept that his conception of a wife was illusory, Ohu would step forward and he would recognize her as the wife he had been seeking all along. Ohu was surprised that this outcome, as obvious as it appeared now, had not dawned on her earlier.

She discreetly glanced over at her passenger and considered a lifetime spent in his company. It seemed passably agreeable to her. Naturally, she said nothing of her revelation to her future paramour. The sequence of events had to play out in their appointed order. She resolved to wait patiently, despite the giddy anticipation she now felt, for her moment to arrive.

Later, during the same drive, it occurred to Ohu that there might be another destined to step into the shoes of the astronaut's fictional wife. She mentally lined up the possible candidates. There were only two, herself and Samudra. It was at this point that Ohu began to consider the drowned woman as a rival for the affections of the astronaut.

|

|

|

|

|

January 14, 2018

The Country Hospital

Already contacted by the astronaut, the records staff at the hospital had a prepared a copy of their paperwork. It was a simple matter for him to produce his discharge papers and establish his identity. (He, of course, had no driver's license; the only vehicle for which he had any training as a pilot was a spacecraft.) On the admission papers, the name of the paramedic who had delivered the astronaut to the hospital was both printed and signed.

Ohu and the astronaut sat in the hospital cafeteria, pondering their next move. Since the round trip to the rural medical center was three hours, they optimistically hoped to make additional progress today, despite the fact that it was Sunday. Between the two of them, they did not possess a smart phone. However, a visitor, nursing a coffee at an adjacent table, overheard their conversation and, as is the way for helpful, country folk, found the fact that they were strangers no obstacle to making a sensible suggestion.

"If you want to find an ambulance driver," said the old woman, "you don't need to go any farther than the entrance to the emergency room. I see them out there all the time."

Ohu and the astronaut thanked the woman. Having no better alternative, they wandered in the winter chill over the hospital grounds, following signs that pointed, in a seemingly circuitous route, to the emergency room. As the woman had predicted, there was an ambulance parked outside the entrance. The driver leaned against the far side of the vehicle, smoking a cigarette, though it was against policy to smoke on hospital grounds. His partner was finishing paperwork inside the hospital.

When they approach the man, he scanned them in cursory manner, suspecting that they would ask him for directions while debating whether he needed to extinguish his cigarette. He looked at the name at the bottom of the sheet they showed him. "Yeah," he said in a country accent, dropping the cigarette on the asphalt and grinding it underfoot. "I know Sammy. Whaddya want with him?"

"He brought me to the hospital months ago from an accident," explained the astronaut. "I lost something in the accident. I'd like to go back and look around for it, but I am not sure of the location."

"Months ago?" said the driver, shaking his head. "Don't think it's too likely he's gonna remember that. Can't remember everything. We gotta go on a dozen runs a day."

"We've got to try. Do you know how we could get a hold of him?" Ohu asked.

The driver shrugged. "Best bet is to go up to the Wal-Mart."

"Wal-Mart?" said Ohu.

"He and Amy like to wait in the ambulance in the parking lot there."

The ambulance driver gave them simple directions to a shopping center that was located about six miles outside town, strategically placed between several small towns.

Ohu and the astronaut thanked him. He nodded gruffly; he hadn't done them any great service.

"I like country people," said Ohu as she and the astronaut walked away. She was happy that they were making such good progress in their investigation. "They are always so friendly and they don't think anything of it."

The astronaut smiled; although Ohu's observation was accurate, it was not how he would have characterized the encounter.

|

|

|

|

|

January 15, 2018

The Paramedics

Ohu and the astronaut approached the ambulance parked in an isolated spot at the edge of the expanse of asphalt. An obese man with a scruffy beard filled the entirety of the driver's seat. Beside him, a much smaller woman, garbed in matching uniform and endowed with a permanent, no-nonsense look, read the newspaper. When the pair stood at the driver's side window, the man looked up from the phone on which he had been playing a game to pass the time until the next call arrived from dispatch. The engine of the vehicle was running and the heat was turned on, but it was apparently too warm inside for the windows were rolled completely down. The ambulance driver glanced up from his phone only to mutter, "We're working," before he returned his attention to the screen.

The astronaut called him by first and last name, which prompted him to grunt in irritation and shut off the phone. "That's me," he said. "Who are you?" From the passenger seat, the woman folded the newspaper in her lap to observe the unusual exchange.

"I had an accident somewhere near here last summer," said the astronaut. "According to these documents, you delivered me to the hospital." He offered the papers as evidence.

The driver made no move to accept them. He suspected this was a legal trap, that he was being served a subpoena as part of some malpractice suit. "Don't want nothing to do with that," said the driver and he shifted in his seat in order to activate the switch that raised his window.

"Wait," called Ohu as the glass rose. "You're in no trouble. We only want to know where the accident was."

The driver left the window at a halfway position. "How am I supposed to know that?"

"Do you remember?" asked Ohu.

"Remember what?" The driver seemed insistent on not cooperating. He embarked on an impromptu litany of the numerous things he had forgotten recently, including feeding his mother's dogs, all of which were of much greater importance than the location of every two-bit fender bender. He concluded by emphatically exclaiming, "How could I possibly remember you or your accident?"

"It might have been an unusual crash," said the astronaut.

"In what way?" asked the paramedic in the passenger seat, speaking for the first time. She appeared to be willing to make a somewhat more helpful effort than her partner.

"Perhaps the vehicle seemed unusual?" offered the astronaut.

"Last summer?" said the paramedic, "You mean the spaceship."

"Yes," the astronaut agreed. "I mean the spaceship crash."

"You ain't gonna find nothing there," said the driver. "That's been combed over by every curious old man with a metal detector within thirty miles. They all wanted to get their fingers on a piece of the pie before the Federal Government sent in their gun-toting, jackbooted thugs to wipe the area clean and insist this never happened and turn this into another Roswell that nobody never heard of." How much of this cryptic scenario had actually come to pass was not clear and the driver made no further attempt to elaborate.

"Where is the crash?" the astronaut asked again.

The paramedic gave them simple directions. It was another dozen miles along a winding path that led through a mountainous ridge, separating this state from the southern border of the adjacent state. "You can't miss it," said the paramedic. "You cleared out a hundred foot stretch of woods when you left the road on that thing."

When the astronaut asked for an additional landmark, the woman offered, "It's almost across from the Prime Minister's place. You can't miss that either. It has a big old sign says, 'Marge's Baked Goods' out front." The astronaut thanked her. As he stepped away, Ohu stepped forward.

"Is it really a spaceship?" she asked. She feared that the existence of a spacecraft lent unwelcome credence to the astronaut's claim that he was married to a fellow astronaut.

The no-nonsense paramedic released a scoffing bark. "Course not. Just some tricked-out buggy that the locals got all worked up about. 'Cause they got nothing better to do." The woman appeared willing to say more but the dispatcher's voice crackled over the radio and the conversation was abruptly truncated by a brief exchange followed by the blare of the siren.

They watched as the ambulance pulled away. When the flashing lights had moved off down the road and were out of sight, Ohu openly studied the astronaut's face. He observed her with equal scrutiny. Both attempted to determine how much this information reinforced the suspicions or doubts of the other. For her part, Ohu failed to detect any self-righteous vindication in the expression of the astronaut. For his part, the astronaut tried to assess the impact of what he considered to be irrefutable corroboration of his story that no one, save Wouldn't, had ever believed. At the end of this unintended stare-down, Ohu exclaimed happily, "Tony, you have beautiful green eyes!"

|

|

|

|

|

January 18, 2018

The Site

They had to return the car to Samudra by four p.m. It was already 1:45, leaving them only forty-five minutes to find the crash site and investigate it, before embarking on the ninety minute return to town. "I don't want Samudra to be mad at me," said Ohu, as she drove up into the mountains. "We should save this for another day." Her suggestions fell on deaf ears.

The mountains were heavily wooded, though in winter they could see far up the slopes into the interior of the forest as they traveled along the road. Along most stretches, the ground fell away just beyond the guardrail in steep, snow-covered precipices on one side and rose along the other. Worried about returning the car late, Ohu pressed the gas a little harder, increasing her speed, despite the nearly continuous series of curves the road was forced to take as it navigated its way from one side of the ridge to the other. Posted at the most extreme cutbacks, signs cautioned a top speed of ten miles per hour. At each of these, the astronaut was swayed right or left as Ohu tackled the turns at speeds well past the advised limit.

"Slow down," urged the astronaut. 'I've already crashed once on this road."

This innocent comment induced a feeling of déjà vu in Ohu. It occurred to her that perhaps she was the astronaut's original wife. Perhaps, they were now recreating the previous accident. They were caught in a loop, in which they crashed, awakened in a hospital without their memories and, in seeking an explanation, crashed again.

As Ohu was occupied by this revelation, they passed not a single car. This encouraged her to drive faster on the periodic straightaways until, in the shadow of a high peak, they hit an extended patch of ice. Nothing but good fortune can be credited with the car keeping to the road as it glided along this stretch completely outside her control until they emerged from the shadow and the rubber of the tires jerked, regaining traction with the concrete pavement.

Ohu brought the car to nearly a halt on the empty road. At a loss for words, Ohu, blanch-faced, turned to the astronaut.

He found that he had been clutching the edges of seat with white knuckles. He looked over at Ohu and likewise said nothing.

It took a moment to regain their composure. Eventually, Ohu offered, "No wonder there is no one else on this road. It's covered in ice."

"Just drive more carefully," the astronaut said, not ready to give up.

"Then you drive," Ohu said. She stopped the car on the road.

The astronaut had no experience operating a vehicle of this kind. "Fine," he said in defeat. "We'll turn around at the next opportunity."

Ohu began driving slowly again. "We'll come back," she promised.

"After the spring thaw?" The astronaut failed to disguise the disappointment in his voice.

The road continued to rise as it approached the summit of the ridge. They could have guessed that there were no crossroads. They looked only for a driveway, where they could pull in and reverse the direction. Ohu might have managed to navigate an about-face on the narrow mountain road, but she was not inclined to do so, lest another vehicle abruptly appear around the next corner and collide with them in mid-maneuver. As such, they crept another ten minutes along the winding road until they encountered a drive.

It was a gravel parking lot on the left, large enough to accommodate no more than three vehicles, stretched lengthwise parallel to the road. Behind the pull-off, situated on a half-acre plot of land, with a mountain rising directly behind it was a dilapidated building. A sign hung from it that would have read 'Marge's Baked Goods' had all the letters been present. Instead, the only letters that remained spelled out, 'Ma___'s Ba__d G_od_', an ominous portent, to be sure.

The building itself appeared to be the archetypal model upon which all horror movie sets of isolated, rural ruins were based. The first floor of the building had been constructed of cinder blocks in the shape of a perfect rectangle. A primarily wooden second floor had been added at later dates in various, shapes many of which shared at least one right angle in common with the rest of the structure. While the first floor had once been painted white, it seemed that the painters had applied leftover gallons of undesirable colors, purchased at great discount, to the various portions of the second floor. Color mattered little for the entire structure had for some time been entirely claimed by kudzu. In the winter, this wilted vine covered the house like an invasive, funereal pall coarsely woven in woody shades of brown.

Although this structure presented no invitation to so much as linger in its presence, Ohu was desperate to turn around. She managed to bring the car around until it rested in the gravel lot, facing the desired direction.

Before she pulled back onto the road, the astronaut called out, "Wait!" Not far down the road, he had spotted a section of the guard rail that had been violently bent backward. "I think that's it."

"What?" asked Ohu.

"I'm going to get out, just for a moment."

Ohu fixed him with an incredulous gaze. She pointed at the decrepit structure next to them. "Here?"

"Yes," confirmed the astronaut.

"This," said Ohu, gesturing emphatically at the building, "is where the murderous, cross-eyed, chainsaw-wielding hillbilly leaps out from behind the vines."

The astronaut examined the building again. It obviously had not been occupied for decades; there was little to worry about. "We're here," he said with emphasis. Pointing behind him, he added, "I think that's the crash site."

He opened the door and left the car. Ohu watched him in the rearview mirror as he began walking toward the crumpled railing. She leaned over and nervously locked his door. She debated whether to join him. Finally, she turned off the engine and, grasping the key firmly, exited the car, locking the door behind her. As she skipped a few steps in the street to catch up with the astronaut, from the corner of her eye she imagined she saw movement in a dark, vine-covered window on the second floor.

She raced to the side of the astronaut. "There's someone in there!" she hissed in a whisper.

The astronaut paid her no mind whatsoever. All his attention was fixed on a spot a hundred feet away. If one mentally attempted to reconstruct the accident, the vehicle must have been moving at a high velocity, beyond any reasonable measure of safety for these roads. Just before the sharp turn, the vehicle appeared to have hit a small dip in the road, which served as a launching point, allowing it to brush the top of the guardrail as it careened over then sailed down the slope, leaving a perfectly straight track cleared now of all saplings and threaded between any larger trees that might have stopped the vehicle, except for the enormous tulip poplar at the end of the track, where the vehicle had eventually come to rest.

A vehicle of any type--automobile or spacecraft--was absent. There were signs in the trampled underbrush and the collection of garbage--plastic beverage bottles and junk food wrappers--that the site had been repeatedly visited by curiosity-seekers. The astronaut surveyed the ugly gash that the crash had left in the forest. He had hoped that this sight might prompt some memory buried within himself, but no sense of familiarity arose.

Ohu gave him only a minute to take in the scene. She repeatedly looked over her shoulder for the maniac to appear, her ears keenly attuned to the sound of chainsaws. "We need to go," she said. These words seem to have no effect on the astronaut, lost in a trance from which he yet hoped some meaning would emerge. "We're going to be late," Ohu urged. "We'll never get back here if Samudra won't lend us her car again."

It was the logic of this practical argument that jarred the astronaut from his reverie. Ohu clutched his arm, almost dragging him down the road back to the parked car. She continuously scanned the building for any signs of movement. However, they reached the car without incident. She remained so nervous that as she tried to start the car, she dropped the keys on the floor, where they slid under the seat. It took only a few seconds for the combined efforts of the Ohu and the astronaut to locate the keys. When their heads popped up above the dashboard they were unpleasantly surprised to find the Prime Minister standing directly in front of the vehicle, with her two outstretched palms laid flat on the hood, as if she were, by the act of laying on hands, administering a curse to the mechanical fate of the car that had so irresponsibly carried these trespassers into her realm.

|

|

|

|

|

January 19, 2018

The Prime Minister

The astronaut thought that perhaps the old woman had lost her balance and placed her hands on the hood of the car to steady herself, but as she continued to leave them there and glared through the windshield with undisguised hostility, he was forced to accept such was not the case.

Beside him, Ohu whispered under her breath, "What is she doing?"

The two sat in the car for a moment and observed the woman. In every aspect, she seemed the result of a life stricken by poverty, both material and emotional. She donned a down-stuffed winter jacket as one might has seen on ski slopes three decades earlier. By what path it had fallen into her possession was only one thread of an unappealing story of hardship, for it was impossible to imagine her engaged in any form of recreation, not pinochle nor church bingo and certainly not skiing. Upon her hands, gloves revealed as many scrawny fingers as they hid. Upon her head sat a knitted cap from which scraggly gray hair fell across a face, wrinkled with age, sun and a history of unalleviated stress.

She wore her animosity plainly as if it were the only form of self-expression of which she was capable. Although Ohu and the astronaut were strangers to her, the crone seemed to harbor some great resentment for them, perhaps because they, in a late model car and in recently laundered clothes, were casually passing through this mountain nightmare that was her lifelong prison.

When Ohu started the car, the old woman began to shriek, directing her words to the astronaut, whom, by some means, she seemed to identify with the crash. "You'll never find it!" she cried. "It's long gone!" She pounded the hood of the car with a fist.

Ohu put the car in reverse, jerking away. The old woman had not expected this maneuver. She fell forward, face first into the gravel. Ohu continued backing up until she had a clear view of the old woman on the ground. She shifted into drive and swerved onto the road. As they passed the old woman, the astronaut looked out the side window. His concerns that they might yet have to stop and tend to the woman were assuaged when he saw her push herself up onto her hands and knees. A woman as hardened as she would not be stopped by so minor a fall.

As Ohu drove recklessly down the mountainside, the astronaut repeatedly cautioned her to slow down. Eventually, he succeeded and, once again at a reasonable speed, Ohu collected herself and asked, "Who in the hell was that?"

The astronaut had been considering the same point. Putting together what evidence had been presented to him, he summarized his conclusion thusly, "I believe that was the Prime Minister, former proprietor of Marge's Baked Goods."

Needless to say, they were late in returning the car to Samudra. Although she clearly sensed the two had a story to tell, she did not stay to hear it. She was in a hurry to make her previous engagement.

|

|

|

|

|

January 21, 2018

A Prayer for Those Embittered Beyond All Reason

Lord, pity us, Your people, for there exist

a thousand ways for us to lose ourselves.

I shall not, by any means, enumerate them

here. I shall restrain this prayer to just one

error. Soothe especially, Lord, those people

who have experienced so little practical aid

in their dire need, so little regard for the sanctity

of their person that they harbor an intransigent

distrust of all help. Quell the bile that threatens

to overflow, a reflexive action in response

to the approach of acquaintances and strangers alike.

Unwrap these abandoned souls from the cocoon

in which they have enclosed themselves,

in misguided attempts to tend their angry

injuries. Lord, we accept without reservation

the claim that such damage was rendered

by the idle hands of men. Still, we implore

Your divine intervention to mend what

we have broken, for having scrutinized

the details of the twisted wiring, the ground

and corroded cogs, we admit that the procedure

by which the underlying heart might yet be reclaimed

requires something akin to a miracle, something

utterly beyond our mortal ability to produce.

|

|

|

|

|

January 22, 2018

The Iron Lady

The snow on Wednesday, though it barely amounted to an inch, wreaked havoc on the city, accustomed to mild winters. Cars accumulated in ditches along the sides of winding roads. Before two days passed, rain arrived with warmer temperatures and the snow, flake by flake, disappeared under the impact of raindrops. With the roads restored, Samudra succumbed to an idle impulse to visit Lake View.

Beneath an umbrella, she listened to the tree admonish her for failing to attend to Ohu and the astronaut, both of whom had braved the snow by bus to visit with the tree.

"Ohu, in particular," he said, "seemed quite shaken by the events. Her feelings were hurt when you didn't stay to let her tell you what had happened."

"I had to go. I was late," Samudra said. "I told them to have my car back by four. Besides, she told you what happened, didn't she?"

"Yes," said the tree.

"Then you can tell me."

"It's not the same," the tree gently protested.

"Why not?" Samudra asked in a stubborn tone.

"Because I will gain no sense of relief from having shared the story. These are not my fears that must be diminished in the light of calm reflection."

With such an introduction out of the way, Wouldn't related to Samudra the progress that Ohu and the astronaut had made in their search for the crash site, making sure to include in his retelling all of the minor players, including the helpful woman in the hospital cafeteria, the two paramedics in the ambulance, and the Prime Minister.

"I don't get it," Samudra said. "Why did they call her the Prime Minister?"

"I assumed," said Wouldn't, "that it was because she bore some resemblance to Margaret Thatcher."

"Marge's Baked Goods?"

"Perhaps, they have more in common than a shared first name."

"I think you are stretching things..."

"I worried much the same thing, so I went to the library," said Wouldn't, "and borrowed a book of speeches by Thatcher."

Samudra examined the roots of the oak tree, buried deep in the ground. "How did you get to the library?" she asked.

"I have my ways," Wouldn't replied without further explanation. "They called her the Iron Lady."

This historical fact seemed vaguely familiar to Samudra. "Is she still alive?"

"I have no idea," admitted Wouldn't. The book he had accessed had been published decades earlier, at the end of her public life. "I committed part of a speech to memory. Would you allow me to recite it to you?"

"Be my guest," said Samudra with a bemused smile on her face. She found it a pleasant surprise that something she had not anticipated was about to befall her. She stood quietly as the rain drops struck her black umbrella and the arboreal voice of Wouldn't read with a melody that was almost certainly absent from the original delivery of the speech.

"The Russians are bent on world dominance, and they are rapidly acquiring the means to become the most powerful imperial nation the world has seen. The men in the Soviet politburo don't have to worry about the ebb and flow of public opinion. They put guns before butter, while we put just about everything before guns. They know that they are a super power in only one sense--the military sense. They are a failure in human and economic terms. But let us make no mistake. The Russians calculate that their military strength will more than make up for their economic and social weakness. They are determined to use it in order to get what they want from us." The voice of the tree fell off.

After a few moments of silence to ensure that the tree was indeed finished, Samudra pointed out, "As near as I can tell, it didn't turn out that way."

"Ah!" cried the tree, as if Samudra had provided some important piece of evidence. "I hadn't realized that." In his defense, the tree generally made an earnest attempt to avoid knowledge of human institutions, governments first and foremost.

"What does this have to do with Tony's wife?"

"Isn't it obvious?" asked Wouldn't.

"I have no idea where you are going with this," Samudra replied with a laugh.

"The world must be balanced. If there were two Iron Ladies, one on each side of the Atlantic, it is unlikely that they both met with success. Where one succeeded, the other must surely have failed."

"Hmm," Samudra said with a quiet but unmistakably sarcastic tone. "Are you suggesting that the Russians have invaded the northern border of our state?"

"No," said the tree, after considering the possibility. "I suggest only that our local Prime Minister believes completely that she failed to secure the promise made at the end of the speech."

"And that promise was?" asked Samudra.

Wouldn't again adopted the melodic tone in which he recited the closing call of the speech, "Let's ensure that our children will have cause to rejoice that we did not forsake their freedom."†

By this circuitous route, Wouldn't intimated the role that the Prime Minister's unfortunate child would play in the search for the astronaut's wife.

†Speech at Kensington Town Hall ("Britain Awake"), January 19, 1976

|

|

|

|

|

January 25, 2018

The Back-up Plan

Ohu had every intention of accompanying the astronaut on the following Saturday, as he resumed his search for his wife. They had met during the week in the presence of Wouldn't and had, between the three of them, come up with a very sensible plan. Accordingly, the astronaut had used the phone at the computer repair shop (during his lunch break) to contact the Hawkins County sheriff's office. The officer on duty informed him that all vehicles involved in accidents were towed to the police impound lot. Those that were not claimed after three months suffered one of two fates. If the vehicles were in passable condition, they were auctioned off to the public and the proceeds were added to the on-going police cruiser replacement fund. Those that were deemed totaled by an insurance appraiser or drew no bids at auction were hauled off to the junkyard.

Although, the astronaut chose his words carefully, when he asked about the spaceship, the officer pretended there was static on the line and claimed he could not understand him. After repeating himself twice, the astronaut gave up and posed a different question. "Do they all go to the same junkyard?"

"Of course," said the officer. "There's only one in the county. Look, we shouldn't tie up this line any longer..." So ended the conversation.

A cursory search on the internet identified the name and location of the junkyard. An additional phone call to a locally owned and operated business, identified as Hawkins County Scrap Metal, confirmed that the facility was open on Saturdays from eight until noon. "Sometimes we lock the gate fifteen minutes early," warned the man's voice on the telephone, "if it's slow...which it mostly is."

As agreed, on Saturday morning, the astronaut took the seven o'clock a.m. bus that passed Ohu's apartments, where she would join him. Together, they would take that bus to the hub, where they could transfer to another bus that, after half an hour, left them within a couple blocks of Samudra's suburban home.

Ohu waited patiently for the bus to arrive. When it was a few minutes late, she thought nothing of it. The bus system was never particularly reliable. After fifteen minutes, she began to worry. She seemed to recall a few weeks ago seeing a note posted on the pole next to her stop about a temporary detour due to construction along the regular route. She searched for this note but could not find it. In her imagination she tried to reconstruct the contents of the note, until she was fairly convinced it was a real memory. She hurriedly ran one block over to a reasonable guess of an alternate route, where she hoped the bus had not yet come. In that way, she was not present when the bus arrived late at its ordinary stop.

Therefore, at five minutes to eight the astronaut found himself alone as he carefully navigated the concrete path from the driveway to the front door of Samudra's home. The ice had partially melted before refreezing overnight, leaving a sheet as slick as glass. He knocked on the door.

"Where's Ohu?" Samudra asked him, standing in her pajamas. She held the door open enough to seem friendly but not so far as to allow the morning chill to enter the house unimpeded.

"I don't know. She didn't get on the bus."

There was a pause before Samudra said, "I didn't think that you could drive."

"I don't," the astronaut confirmed.

"Then you had better go home. You will have to get Ohu to take you next Saturday."

"I have made an appointment at the junkyard for today," said the astronaut gently.

Samudra clearly understood the implication of his words. "Don't look at me," she said. "It's almost two hours to get out there."

The astronaut stood quietly on the doorstep, thinking of how best to compose his words. "My wife..." he began.

Samudra sighed and closed the door none too gently.

The astronaut waited patiently in the morning chill until Samudra emerged bundled in her coat and scarf and strode briskly to the car. In her hurry, Samudra slipped on the slick ice and would have fallen had the astronaut not caught her by the elbow from behind.

"Be careful," he urged her, setting her upright.

She mumbled a begrudging thanks. Thus, Samudra and the astronaut traveled north with hopes of finding signs of his wife left in the damaged spaceship, which according to a logical interpretation of events, should have been waiting for them somewhere in the vast, refuse-filled acreage of the Hawkins County Scrap Metal lot.

|

|

|

|

|

January 26, 2018

Driving in the Country

Samudra entered the address of the junkyard in her GPS, depriving the astronaut of his utilitarian role as navigator. Instead, he sat quietly beside the woman. Once they had emerged from the city limits, he allowed the pastoral hills to work their calming influence on her. Before long, Samudra succumbed to the placid charm of old barns and isolated silos. She maintained, however, her reservations against the value of this trip.

"Tony?"

"Yes." He looked over but could not penetrate her expression behind her large, fashionable and darkly impenetrable sunglasses.

"Did the man at the junkyard say that he had your spaceship?" It proved hard for her to voice the last word with sincerity. Doing so, only made her feel like she was encouraging the delusions of a madman, which in turn engendered in her the return of the stubborn resentment she had felt when her own parents had insisted that she begin therapeutic sessions with a psychiatrist. She had always known there was no madness lurking within her. She glanced over at the astronaut and reminded herself that he likely perceived himself in much the same way.

"We did not discuss the spaceship explicitly," admitted the astronaut. "I feared to do so might prevent him from meeting with me or even allowing us access to his yard."

"Then this could all be a wasted effort."

The astronaut nodded. He did not elaborate on the thought, which occurred to him then, that the same could be said of many endeavors in life. Sometimes, if one capitulated to a pessimistic impulse, one might make the same claim of life in its entirety. There was little to be gained from such a stance. Consequently, the astronaut chose to repeatedly err on the side of optimism.

This was not the only conversation that transpired during the two hour drive to the rural junkyard. The drowned woman and the astronaut spoke of numerous trivialities that shall not be recounted here, for they served only to establish a commonality between the two, which while superficial was nevertheless genuine.

Only one additional fragment of the conversation shall be documented here. Samudra, still trying to rationalize some purpose in this expedition that would consume an entire Saturday, asked the astronaut, "What is your wife like?"

"My wife," replied the astronaut in a dream-like tone. He had spent so much time with her in the restrictive confines of the spacecraft that he had come to know her, mentally, emotionally and physically, with great intimacy. Thinking of them in that shared space, he said from his reverie, "She has a smell to her person that to me is the essence of security and of belonging..."

Having expected a physical description, perhaps the color of her eyes, Samudra was surprised by the astronaut's words. For a while, she left him in the memory of his wife and did not pursue any further questions along this line.

|

|

|

|

|

January 27, 2018

The Junkyard

The soil of Hawkins county had long been regarded as fertile. In the stretches of plateau, tomatoes and other local agricultural products had gained national renown. On the slopes of rolling hills, cows were pastured. The eye was drawn to the intricacies and nuances of the lands and the manner in which men had made good use of it. Upon observation, the mind was lulled into fantasies of former, more idyllic times.

It therefore came as a shock to both eye and mind, when the road rounded a hill and Hawkins County Scrap Metal came into view. It happened to be situated beside the county landfill. Thus on the right, a man-made mountain of garbage rose into the sky. A lone bulldozer rumbled atop it, shoving piles of recently deposited trash over a ridge and out of sight.

To the left, the junkyard rose with a gentle incline, providing a clear view of the expansive array of automobiles, arranged in lines that stretched as far as possible, until they encountered a ridge or a creek bed or some other natural obstacle that had prevented the accumulation of additional vehicles. Many thousands of vehicles were thus aligned with narrow grass-covered aisles spaced every few rows to allow a truck to escape with plundered parts. The range of ages of the cars present attested to the history of the junkyard, which spanned many decades. Some cars were entirely reduced to rust, while the chrome of others sparkled in the clear, winter sun. Arranged on the slope in this manner, the automobiles reminded Samudra of pastries displayed on a tray, tilted at an angle so that the particular delicacies of each were plainly evident to the customer. She made such a comment to the astronaut, who did not reply. He had not gotten past the shock of what he considered a terrible misuse of good soil and the spoiling of a naturally majestic landscape.

Samudra turned off the county road down a gravel path that led into the junkyard, passing a metal gate that had been left open. She stopped beside a white, aluminum mobile home, which presumably served as the office. Beside it two cars were parked, each in a condition which seemed to express a yearning to join their compatriots in this mechanical purgatory.

No one came to greet them nor were did anyone respond when the astronaut knocked at the office door.

"I thought you had an appointment?" said Samudra.

"I do," the astronaut assured her.

They milled around in front of the mobile home for ten minutes, waiting for someone to appear. Eventually, their patience was rewarded by the sound of a sputtering truck engine. It gradually appeared from the depth of the junkyard and two men emerged from the truck. They observed the pair of strangers. The larger man hollered at them, "Be with you in a minute." Samudra and the astronaut watched them move a car door from the bed of the pick-up into the trunk of one of the vehicles. Money changed hands and one man left in the vehicle, managing a four-point turn to reverse his vehicle and to narrowly slip past Samudra's car.

The other man, whom we shall now identify as the proprietor of Hawkins County Scrap Metal, then approached them. His character is interesting only in that it combined several traits common to the rural population of the state. In recent times, an epidemic of obesity had settled in this land. The origins of the epidemic could largely be traced to local social and economic policy, which, in the spirit of independence and self-determination so valued by its people, did little to enforce statutes that encouraged healthy living and, on the contrary, allowed each individual to arrive by choice at an unhealthy condition. Their decisions to engage in poor dietary habits were made easily accessible by the fast food restaurants and gas stations which sold the junk food on which they subsisted and which profited handsomely. In short, the proprietor was morbidly obese. Garbed in a workman's overall, he had barely fit behind the wheel of the truck. His eyes seemed reduced in size by his swollen face and the folds of flesh beneath his chin were covered in scraggly whiskers.

Even before he spoke, Samudra observed his labored breathing. As he greeted them, she found him incapable of speaking in extended sentences. He had to break up the pattern of his speech in order to catch his breath. He wheezed almost continuously, as if he suffered from chronic emphysema. He withdrew a pack of cigarettes from the chest pocket of his overalls and began smoking as he greeted him. Of course, we also understand that the shared duplicity of tobacco corporations and the lackadaisical oversight of a federal government under the sway of the tobacco lobby was responsible for the preponderance of rural citizens who continued to smoke, even in an age when there was no longer any attempt to hide the detrimental effects of the habit.

A third attribute of the proprietor, shared in common with many of his neighbors, was his unrestrained sociability. He greeted Samudra and the astronaut as if they were old friends, smiling continuously as he, in gasped phrases, expounded the many hidden, treasures that could be unearthed within his junkyard. With a self-deprecating humor, he patted his belly and said, "If you just tell me what you're looking for, I'll see if I haven't gotten too fat to get back in the truck and find it for you."

"I'm looking for a vehicle that crashed last summer across the road from Marge's Baked Goods," said the astronaut.

"Huh!" laughed the proprietor. "You and everyone else! You're only about six months too late. I was fixing to make a pretty penny off that spaceship. There was all kinds of interest in that one." He paused to catch his breath then sucked on the cigarette. "You don't see a spaceship every day. The insurance company wouldn't let the sheriff sell it--too much liability for the state it was in--it was completely wrecked--or he would have auctioned it off himself. As it was, the contract with the county delivered it to yours truly." He jerked a fat thumb at his chest. "And I set up my own auction."

"You auctioned it off?" asked the astronaut.

"I had it all arranged," said the proprietor, shaking his head. "Then some son of a bitch broke in and stole it the night before." He glanced apologetically at Samudra for using language that country folk ought not to use in the presence of a lady.

"That's unfortunate," said the astronaut.

"And I reckon I know who stole it."

"You do?"

"Sure I do."

"Then why didn't you go to the police and get it back?"

"Fucking-A, man" said the proprietor, apparently forgetting the presence of Samudra. "You don't mess with the Prime Minister. She killed her own husband, bastard that he was. Everybody knows it."

|

|

|

|

|

January 28, 2018

The Junkyard Proprietor

Finding he had an eager audience that could suffice as company on a slow Saturday morning, the junkyard proprietor invited Samudra and the astronaut out of the cold wind and into his office. Samudra, for her part, would have preferred to hear whatever had to be said out in the open, even had there been a blizzard. However, the astronaut cordially accepted the proprietor's suggestion and followed him inside.

Samudra found an office which seemed to serve as kind of nest for the giant man, in which every spare surface was plastered with layers of old paperwork, expired titles and receipts, all conforming vaguely to the shape of a desk, file cabinets, and a pair of chairs. The only clearly uncovered furnishing were an electric coffee maker with half a pot of coffee still hot and, alarmingly, an electric space heater, currently running, balanced casually atop a stack of old newspapers.

There were only two chairs and one was already occupied by the proprietor. Samudra declined the other, keeping a close distance to the door should the office abruptly flash into a conflagration.

In his office, the proprietor reclined in his chair and enjoyed the retelling of the murder of the Prime Minister's husband. Amidst wheezes and gasps, the story unfolded in a natural way, granted an authenticity by the country accent in which it was shared. "He was poisoned. The country coroner said there no doubt. Rat poison. The common kind every exterminator uses. Between them, they only had the one son and he works as the exterminator for just about everyone around here who has enough money to hire somebody else to get rid of their vermin. But no more than a passing suspicion fell on the son because, after all, the Prime Minister's a piece of work all by herself. You can count yourself lucky if you never run into her." While he caught his breath, the proprietor glanced up to see if either of his guests had met the crone.

He was surprised when the astronaut nodded. "Oh, you have had the pleasure. Then you know what I am talking about."

The astronaut nodded again and the proprietor continued. "Well, as ill-tempered as the wife may be, the husband was worse. Rumor says he beat her something awful when they first married. There's no justice for an unlucky wife out in the mountains, 'cept that which she takes for herself. I'm not old enough to know how they were before they got hitched, but the common thought is that, cooped up in that bakery all by themselves, they made each other worse over the years. Only thing what kept them in touch with the rest of the community was the simple fact that she baked the most delicious bread to be found in these parts. "I don't suppose you ever sampled Marge's Baked Goods?" The proprietor's eyes glazed with the memory.

The astronaut shook his head. When the proprietor glanced up at Samudra, she shrugged ruefully.

"Anyway, she poisoned him to death. Probably baked it into loaves of bread especially for him. There wasn't much of an investigation, even after the coroner released his report. They were two of a kind and everybody seemed more or less happy that there was one less of them. People reckoned that if they just left her alone she might poison herself too and then the world would be rid of the misery of them both. Anyway, the bakery never reopened after he died. That was years ago, when I was still in school. And she still lives up in the apartment over the shop."

When it seemed the proprietor had reached the end of his story, the astronaut asked, "How do you know she stole the spacecraft?" Clearly, the Prime Minister was unpleasant but no evidence had been presented in the tale that identified her as a thief.

"Well," said the proprietor leaning his bulk over the desk, "she kept saying it was hers by right."

"Why is that?"

"'Cause she shot it out of the sky," the proprietor stated matter-of-factly. Observing the expression in Samudra's face, he added, "Or so she claimed."

|

|

|

|

|

January 29, 2018

The Junkyard Proprietor II

Although the proprietor of the junkyard had up to that point been extraordinarily congenial, when the astronaut requested directions to the home of the Prime Minister's son, he balked. His fear of the Prime Minister even at a distance was great. The proprietor had willingly relayed the theory that the Prime Minister had sent her son to steal the spacecraft; that was common knowledge. His visitors could have learned that much from anyone. He had also speculated that the spacecraft lay resting somewhere on the son's property, situated in a remote vale, accessible by a winding single-lane gravel road that could be traveled only in the absence of rain. But providing directions to the home seemed too much at odds with the designs of the Prime Minister.

"You don't want to go there," he cautioned them. "Road's half washed out most of the time. Besides, he may be a damn sight more approachable than his mama, but he won't take kindly to no uninvited visitors."

The astronaut then thought to locate the home via public records available on the internet. "What's his name?" he asked.

"Prime Rib," answered the proprietor. That much he could freely divulge.

Samudra frowned. "The Prime Minister's son is named Prime Rib?"

"Yep." The proprietor apparently saw nothing odd with a mother and son sharing the same first name. There were other examples that came to mind.

"Like the cut of meat?" asked Samudra, who was a vegetarian.

"Uh-huh," confirmed the proprietor. He studied her expression. It occurred to him only then that she was an attractive woman from a big city (at least relative to his own environs). And the fact that she wasn't unambiguously white or black only increased his suspicion that she might not be in a position to understand the nuances of country living. He therefore sought to explain, though in fact such an effort was entirely unnecessary, the tradition of nicknames. "You know," he said kindly, as if giving a lecture, "lots of people have nicknames after meats. There's T-Bone, Ham Hock, Short Rib and the Hamburger Martyr. You have to match the name to the personality."

"How is his personality like prime rib?" Samudra inquired. Maybe the son was medium rare, she imagined, amusing herself.

The proprietor sensed her condescension, though it seemed not to bother him. "Well, I thought it would be obvious. His mother is the Prime Minister." He said nothing more, as if the logical relation between the two could not be more apparent.

"I see," said Samudra.

The astronaut hoped to avoid a deepening of the culture clash. "You won't give us the directions?" he asked again.

"I'm just a country boy," said the proprietor, shifting his massive bulk in the chair. "I'm nothing without my people. Don't want to get on the wrong side of no one, especially the Prime Minister."

"Thank you for your help," the astronaut said sincerely. He turned to Samudra and moved to the door.

"Can I ask you one question, 'fore you go?"

"Certainly," agreed the astronaut. It was the least he could do. The proprietor had shared a great deal of information useful to their search.

"Why're you interested in the spaceship? You don't work for the government, do you?"

"No, I don't work for the government," the astronaut hastily assured him. "My interest in the spacecraft stems from my claim to it."

"Your claim to it?" said the proprietor surprised. "What claim do you have?"

"I was inside it when it crashed." He did not reveal at this time that there was another passenger, nor did he share his intimate relationship with the other astronaut.

"No shit!" The proprietor rose to his feet in excitement. "I always knew somebody would come looking for it. I was afraid I would have to share the profits after I auctioned it off." He looked up at the astronaut and said, regretfully, "Like I said, that never came to pass."

The proprietor, like many country folk, believed in a simple brand of justice, one that had largely been obfuscated by the civil and criminal court system. A genuine claim to the spacecraft trumped his fear of the Prime Minister. He therefore, without further prompting, provided a rough, hand-drawn map of how one might reach the property of Prime Rib. He cautioned them again and he did extract a promise from both the astronaut and Samudra to never reveal to anyone just who had provided the map.

In truth the proprietor of the junkyard did not believe that such promises would protect him from a karmic retribution should he have erred and his actions prove not to align with an intrinsic, universal justice. Still, he accepted, as he had already admitted to his visitors, that he was just a country boy and he had no intentions of contradicting the workings of the great and magnificent world around him.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This work is made available to the public, free of charge and on an anonymous basis. However, copyright remains with the author. Reproduction and distribution without the publisher's consent is prohibited. Links to the work should be made to the main page of the novel.

|

|

|

|

|

|