|

|

|

|

The Poison Pie Publishing House presents:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

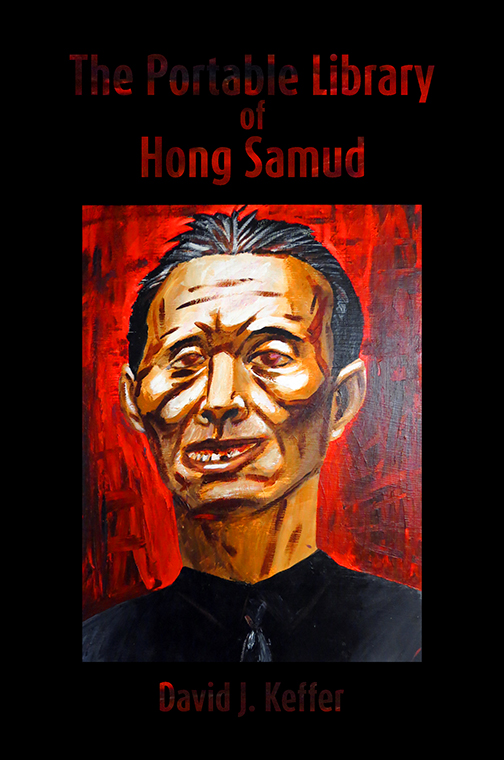

The Portable Library of Hong Samud

(link to main page of novel)

September

|

|

|

|

|

September 1, 2015

On the Unexpected Expansion of the Library

The spiraling library of Hong Samud grew with his acquisitions. He maintained a catalog of rooms, describing the theme of the contents of each. Sometimes, he simply paced through the halls, poking his head into one room or another at random, then perusing a book and refreshing his memory.

He was therefore shocked beyond any description of astonishment to discover during one such walk an unfamiliar room. He retreated and moved back a room to assure himself that he knew where he was in the library. He returned to the mystery room, which had refused to conveniently vanish during his absence. Hong Samud entered and pulled a book from the shelf. Despite the millions of tomes in the library, Hong Samud knew each and this one had not entered the library by his hand. Admittedly it was similar to books he had found on the subject of the flora of exoplanets but it included entries for planets that were certainly unknown to him.

Hong Samud sat in one of four wooden chairs at an oak reading table, such as was located in all the rooms that he had willed into existence. There, he willfully engaged what logical apparatuses were available to him and arrived at several potential explanations. Of these, we explicitly note only two. First, he blamed himself. Perhaps, he had lived too long in this library. Perhaps, his mind, or at least his memory, was failing. Perhaps, this room and its contents were acquired by him and he simply no longer recalled them. He found no evidence for such an argument; his mind seemed sharp to him. All other symptoms of dementia were absent in his person and behavior. However, he was unwilling to decisively eliminate his own fallibility or frailty from the list of possible culprits.

Second, he entertained the idea that someone else had gained access to the library without his knowledge. Furthermore, this intruder had seen fit to contribute to the library in a manner wholly consistent with Hong Samud’s design. The evidence in favor of this argument was only that such a room now had appeared before him. Suddenly a sinking suspicion filled Hong Samud.

Leaving the book on distant flora on the reading table (something he never did as he was compulsive about maintaining order in the collection, as any good librarian is), he moved across the hall and discovered a second room filled with unfamiliar books. He then hurried to the next pair of rooms and discovered two additional chambers of books of unknown provenance. And after them, he found another pair. In fact, his reaction fell somewhere between being amazed and aghast that someone had apparently attached an entire library of their own to his library.

This discovery resulted in a period of limited acquisition for Hong Samud, lasting several months, during which he was consumed in the investigation of the library. Rather than recount each discovery as he made it, we shall summarize the principle finding of this period.

To understand these results, Gentle Reader, you must remember that the library was arranged in a spiral, in which one end of the central hallway was connected to its beginning in a closed circuit. That the top of the spiral led to the bottom and vice versa had been established early on. However, walking the full length of the new additions to the spiral, Hong Samud never returned to his original portion of the library. Instead, he concluded that not only one library had been appended to his own but seemingly an infinite number of such libraries had been strung like pearls on a string.

In fact, Hong Samud came up with a much more accurate metaphor for the library. If one recalls that each pair of rooms was arranged regularly around a central spiral, then we can think of the form of the library as following the shape of a double helix of DNA, with each room occupying a position of a nucleic base. It was as if someone had taken the genome of Hong Samud’s library and spliced it with the genome of an infinite number of other libraries.

Eventually, Hong Samud turned around and retreated to that familiar portion of the library that housed his contributions. There, he tried to come to terms with this new development. He freely admitted that he had experienced flashes of something akin to terror upon discovery of an intruder in his library. He had been overly protective of it, allowing no one access. To be sure, he had understood the inutility of a library with no patrons. He had deflected the argument with the thought that he simply wasn’t ready yet. At some point, he would complete a sufficient part of the moral journey that constituted his life and would arrive at a revelation that prompted him to open the doors of library. Hong Samud had accepted the empirical evidence that he simply had not yet reached that enlightened state yet. To find that others had not only accessed his library but altered its contents significantly therefore alarmed him to no end.

However, Hong Samud overcame this initial panic. As he had explored the additional segments of the library, he discovered no flaws whatsoever. The care and meticulous conduct of the alien librarians was clearly equal to his own. He searched assiduously for errors but found none.

Hong Samud had never harbored religious convictions. He had never believed that there was an intrinsic goodness to the universe any more than he had suspected that the universe was inherently inimical to the interests of man. No, he had found the universe to be subject only to a set of physical laws that, given the virtually infinite degrees of freedom in the system, resulted in dynamics that were opaque in their complexity and occasionally gave rise to both beauty and cruelty. The relative proportion of beauty and cruelty seemed to weigh largely on the perspective of the individual.

Thus to find that, without any action on his own part, the library had been magnified infinitely and perfectly, filled Hong Samud with a sensation that he had never experienced before. He savored that sensation and reflected on it for quite some time, eventually concluding that this must be what people described as faith in God.

Rather than succumb to the ecstatic throes of a religious revelation, Hong Samud imagined physical mechanisms for the miraculous expansion of his library. For example, he imagined that in an infinite number of alternate universes, there were parallel realities where individuals like him had conceived of the same idea of this library. Perhaps, one or more of these parallel versions of himself (he liked to think of them as distant though like-minded cousins) was a step ahead of Hong Samud and had realized that there might be other versions of his own library. This duplicate had worked to locate them and then connect them.

Even as Hong Samud entertained such outlandish hypotheses, ostensibly based in science, he found that his recently found faith in an intrinsic goodness dwelling within the universe, and perhaps across many such realities distributed across the multiverse, did not diminish.

|

|

|

|

|

September 2, 2015

On the Purpose of the Library

Before Hong Samud entered the library, he had admired a certain kind of person in the world, specifically those who worked in roles of service toward the reduction of misery and did so with humility. The vast majority of those who fit this description worked in the name of social justice, speaking for the vulnerable and down-trodden, those who lacked the resources and influence to protect themselves from exploitation by avaricious economic and political systems. While Hong Samud admired such people, he could not join them in their cause because the justice they sought was ‘social’ and Hong Samud was, to put it mildly, not a people person. Impractical to a fault, he utterly lacked social graces, a trait that can be accommodated in a university professor but is frankly inconsistent with social work. The preference for the company of books to that of men is not a quality that can be easily hidden; it emerged of its own accord in false steps and misspoken words. To be clear, Hong Samud did not think only of his inability to meet the requirements of a charismatic speaker or leader of causes. He also lacked vital qualities toward fulfilling a more modest and utilitarian role. He was perceived as an awkward, uncomfortable man, in part because his hearing was poor, and his brain was wired in such a way that he could not understand voices when more than one of them reached his ears simultaneously. In his previous vocation, at dinners where faculty hosted visiting scholars, if the table was not located in a quiet nook, Hong Samud could not follow the discussion without repeatedly asking for each sentence to be repeated with greater enunciation, a habit which eventually caused him to be dropped from the list of hosts, much to his relief. However, it was not only sensory traits that rendered Hong Samud poorly suited to social situations. Philosophically, his brain was also wired for a different fight, or, as he came to think of it, the same fight but at a different level.

Hong Samud believed steadfastly in the concept of fairness and railed, internally, against injustices. But from his point of view, addressing the issue at the social level was akin to treating the symptoms and not the cause. At the social level, one had to educate each individual, resulting in a never-ending fight, generation after generation. While it was true that it was not a solitary battle, it was all the same an exercise in inefficiency if not futility, at least in the eyes of Hong Samud.

He believed that effort would be better spent attacking the problem of the inherent unfairness of the universe at its root cause, namely on an existential rather than social level. Rather than seek to change each individual, would it not be far more preferable to change the rules of the game so that justice appeared more naturally?

Of course, it was not clear to Hong Samud how one might remake the universe in such a way that the scales were tipped in the balance of justice. He accepted that such a challenge was difficult, if not impossible. However, he also accepted that to live and die in the pursuit of a noble goal, whether one attained it or not, was ultimately an honorable role. Such were the thoughts that had led him to the creation of the library.

Many readers will observe the impractical folly of Don Quixote in the actions of Hong Samud. This observation surfaced too in the librarian’s own introspective moments.

To be honest, this conception of the grand challenge of his life had not appeared readily to him. On the contrary he had struggled for the first half of his life with reconciling his admiration for those who fought for social justice and what often seemed a conflicting preoccupation with his own existential duress. It was a culmination of his life experiences up to that point that led him to recognize the relationship between the two and formulate a statement of purpose in this matter. Stating the problem was an important but admittedly preliminary step in solving it.

Hong Samud sat in his perfect and infinite library and wondered by what amount his efforts had reduced the sum total of misery in the universe. He harbored a recurring fear that the answer was not one iota.

|

|

|

|

|

September 3, 2015

On a Patron of the Library

A puzzle that continued to perplex Hong Samud was the absence of other librarians. It seemed contradictory that they should be so meticulous in the acquisition and organization of their portions of the library but so derelict in their vigilance over the contents. It absolutely never occurred to Hong Samud that, perhaps, all of the other librarians left that duty to one amongst their number who willingly chose to dwell almost continuously in the library.

Consequently, it fell to Hong Samud to greet the first patron to enter the library.

Upon hearing the unmistakable sound of footsteps, followed by a questioning, “Hello?” echoing down the hall, Hong Samud ran like a man possessed toward the source of the sounds.

He arrived, breathless, before the man. He managed to gasp, “I have waited quite some time for the opportunity to meet another librarian.”

The patron was taken aback by not only the ragged breathing of the librarian but the greeting as well. “I am afraid,” he said, “you have mistaken me for someone else. I am no librarian. In fact, I was looking for the librarian. Do you work here?”

An avalanche of suspicions swept through Hong Samud as he nodded in confirmation. The library had been invaded. Perhaps this was only a scout. Legions of careless, callous patrons might well be right on his heels. His books called out to him in terror. Corners might be dented, spines split, pages smudged or, worse yet, dog-eared.

Apparently, Hong Samud did not hide his thoughts well for the patron looked awkwardly away and asked, “Where’s Janice?”

“Janice?”

“The regular second-floor librarian.”

Hong Samud pursed his lips. He clasped his hands pensively only to find himself wringing them moments later.

“Are you ill?” asked the patron.

Hong Samud remained silent for nearly a minute. He sought the right opening words. Finally, after exhausting a variety of entries, he settled on, “Who are you, if I may be so bold as to ask?”

“My name,” said the patron, obligingly the obviously distressed librarian, “is Anxo. I work as a clerk at the Sigil Insurance Company in town. I have come to the Tower Library for some information required to calculate a rate for insuring a caravan delivering goods to a portion of a distant country along a route with which I am not familiar.”

The only words from this reply that registered in Hong Samud’s memory were “Tower Library”. This insolent patron already had given a name to Hong Samud’s library! Surely the naming of the library was a privilege only of Hong Samud. Indignation swept through him followed quickly by embarrassment for he had wandered a thousand years through these halls and never thought to give a name to the library. Now a Johnny-come-lately had beaten him to the punch. Crestfallen, Hong Samud appeared to lose his balance. Lest he fall to the floor, the patron grabbed hold of one arm and led him from the central hall to one of the chairs about a reading table in the closest room.

Allow us, Gentle reader, to take this moment to describe the physical appearance of both Anxo and Hong Samud. We shall begin with the patron for we have already waited conspicuously long for that of Hong Samud and another paragraph or two is a negligible delay.

Monsieur Anxo, as he was known by both colleagues and clients in the office, was a young man, not yet thirty, of pale complexion and impeccably, upright posture. He endeavored to present an aspect of refinement, part of which came naturally to him and much of which was external affectation. His curly blond hair, luminous gray eyes and pleasingly symmetrical face expressed an intrinsic element of health and good breeding. His fine clothes—a tailored, dark gray business suit favored by those in the insurance agency, a vest beneath the jack of lighter hue, a starched white dress shirt, polished black leather shoes—were common enough among his profession not to raise any eyebrows. But to this ensemble, he added a dapper black top hat and an ebony cane, capped with silver at both ends. He looked every bit the dandy, save the expression on his face, which remained that of an insurance man, one who calculated risks carefully and who took them with utmost caution.

At the risk of alienating some readers, we point out an additional, anomalous feature of M. Anxo, not immediately apparent to the eye. It had long been a legend among the Anxo family that an ancestor, lost far beyond any living memory, had mingled with an angel. They held that the beauty of their family and a disproportionate tendency toward serenity, a trait that sometimes skipped a generation, were manifestations of a residual genetic trace of this benevolent bloodline. Although the story of this family heirloom had been often shared with Anxo, he kept it to himself without exception, for he found it quaint, rustic and frankly embarrassing. The worst part about it was that there seemed to be some element, coincidental or not, of truth to it, for indeed Anxo was handsome beyond average and his self-assured, restrained and dignified air often put clients at ease, filling them with a sense of well-being in the midst of some calamity that had led them to the insurance office in the first place. So Hong Samud perceived this patron.

The patron’s perception of Hong Samud was not quite as flattering. He saw a diminutive man, not much more than five feet tall. His black hair, swarthy complexion and facial bone structure indicated that he hailed from an equatorial nation, perhaps an island of some remote archipelago. If there was ever a man suited to be a librarian, he now stood before M. Anxo, for Hong Samud, with a thousand-years practice behind him, expressed the librarian’s concern for those aspects favorable to the preservation of knowledge in each syllable he whispered, each brisk gesture he made and each reservation that flashed across his face.

After a few minutes seated at the table, Hong Samud resumed his composure. Seeing the librarian returned to his senses, Anxo asked, “Can you help me find the book I am looking for?”

“Of course,” replied Hong Samud, rising to his feet. “That’s what I’m here for.”

|

|

|

|

|

September 4, 2015

On Library Cards

Having provided Anxo the information he required, Hong Samud had yet to discover the words by which he might give voice to the many questions on his mind. When it seemed that Anxo was on the verge of departing, Hong Samud had no alternative but to do his best at jump-starting the conversation.

“So, do you come here often?” he asked, immediately regretting the words for they sounded in his own ears like some clichéd barroom proposition.

If Anxo interpreted the words in this manner, his irreproachable manners forbid him from making any indication of it. He said in an easy tone, “In my line of work, information is at a premium. I often have cause to come to the Tower Library.”

“How is it that we have never crossed paths before today?” asked the librarian.

“Do you always work in the Special Collections wing?”

“Hmm.” Hong Samud digested the idea that his infinite and perfect library was only a wing of a much larger structure. “I suppose,” he replied.

“Then that solves it,” said Anxo, “for I have not had need to venture here before. Often, I seek only mundane figures found in reports and catalogues not destined for the care of Special Collections.” Anxo bowed slightly and thanked the librarian for his assistance.

Hong Samud returned the gesture.

“I can see myself out.”

“Allow me to accompany you to the exit.” Hong Samud desperately wanted to understand how the patron had accessed the library.

In truth, Anxo had formed an opinion of the librarian as something akin to a raccoon or a similar creature that had invaded the attic of the library and chosen never to leave again, subsisting on whatever nutrients it could find, perhaps the books themselves. It would not have surprised Anxo to discover a man-sized nest formed of the torn and crumpled pages of numerous tomes, where Hong Samud spent his nights.

Such thoughts would have presented a mortal affront to Hong Samud, but he remained ignorant of the patron’s speculation and focused only on following him as he walked along the central corridor.

It seemed to Hong Samud that the patron perceived the library, at least in parts, differently than he did for Anxo stopped at the entrance to a room, room number 3,172 by Hong Samud’s accounting, and said, “Well, this is it. I thank you again for your invaluable help.”

“If you have need of my services again, do not hesitate to call,” said Hong Samud, trying to postpone the departure.

Anxo removed a nondescript card from the breast pocket of his coat. He swiped it along the frame on the right hand side of the doorway. Nodding, he stepped through the doorway.

Hong Samud observed him with perfect clarity, standing in a room of the library much like any other, save for the particular nature of the contents of the books that lined the shelves within. “Wait!” he called.

Anxo turned with a curious expression on his face.

“What is that?” asked Hong Samud.

“What? My library card?”

“Your library card?”

“The front desk indicated that the library maintains controlled access to the Special Collections wing. One must check in and out.”

“The front desk?”

“They said it was library policy.”

“Did you get your library card at the front desk?”

“I did,” replied Anxo, “Years ago.”

“I think I shall accompany you down to the front desk. I have a matter of library policy myself to broach with them.”

“I hope I have not unknowingly violated some stricture.”

“Absolutely not,” said Hong Samud. “Were all patrons as careful and conscientious as you, librarians would sleep much easier at night.”

Hong Samud stepped through the doorway. As he had suspected, it served as a portal, for when he emerged he stood not in room 3,172 but in an entirely different library lit by an afternoon sun streaming through the windows on the far wall. It was a humble, municipal library, full of local charm, the decorations of school children on the walls, the smell of treasured books and the character of a building long ago settled into its role. Hong Samud turned and carefully marked the point from which he had emerged. Above the doorway, engraved on a brass plate were the words, ‘Special Collections’.

The librarian followed Anxo through rows of books, down two flights of stairs to the ground floor of the building. There he parted with the insurance clerk, who left the building for the town beyond, depositing the librarian in the care of his fellows who staffed the front desk.

Hong Samud stared through the glass doors at the entrance to the library. From this limited view, he did not recognize the town.

“May I help you?” said a middle-aged woman wearing reading spectacles to which were attached a string of glass baubles that draped around the back of her neck.

“I should like to apply for a library card,” said Hong Samud, in a voice that he hoped did not sound too bewildered.

The process took longer than usual since Hong Samud did not possess any identification documents. During the application process, the librarian remarked on the name Hong Samud, which was not familiar to her. Hong Samud, for his part, was not yet ready to reveal anything about himself, for fear that if he were identified as too unusual or foreign, they would withhold his library card. As part of the process, she took his photograph in the staff room. “It can take up to two weeks for the card to be ready,” the woman told him. “If you provide an address, the library staff can conveniently mail it to your home.”

Having no local address, Hong Samud declined, saying it would present no problem for him to pick it up in person. In the interim, she provided him a flimsy temporary card, with his name printed on canary-colored paper in the font of an old typewriter.

“You’re all set,” said the librarian.

“May I ask you name?” said Hong Samud.

“Mable,” replied the librarian.

“Thank you, Mable, for your assistance,” said Hong Samud formally.

With the librarian’s eyes on him, Hong Samud retraced his steps to the stairwell. He ascended back to the third floor and returned to the entry to the special collections wing. He swiped his paper card in front of the scanning pad just as he had seen the insurance clerk do and stepped forward. The fact that there was no magnetic signature embedded in the atoms of the paper card disturbed the librarian not in the least.

He emerged back in the central corridor of his library just outside of room 3,172. The portal closed. Several times he stepped through the ordinary doorway without swiping the card, simply to confirm that the familiar geometry of his library was still accessible to him.

Having satisfied himself that this was the case, Hong Samud began to pace the hallway, entertaining one very specific suspicion. He fingered the cheap paper of the library card. At each doorway, he paused. It seemed highly likely to him, almost inevitable one might say, that each and every door in his library, once activated was connected to another library, lodged firmly in a physics-based reality.

This connectivity between his perfect, formerly inviolate dream and a reality that now enveloped it on all sides suffused the librarian with a peculiar sensation in which a shocked dismay and a curious hope were inextricably mingled.

|

|

|

|

|

September 8, 2015

On the Descendants of Angels

Alone in the library, Hong Samud contemplated whether the visit by the insurance clerk had been nothing more than a hallucination, brought on by his extended isolation. However, the flimsy library card provided physical evidence to the contrary. The librarian spent a considerable amount of time ruminating over the visit, reliving each detail and attempting to decipher ulterior motives and meaning.

A second and far more convincing piece of evidence emerged when he discovered the presence of a new pair of rooms in the library. Apparently, the clerk had brought his own books with him and deposited them in Hong Samud’s library. The librarian stifled his indignation at the presumptuous donation and set to work examining the books.

His first observation was that the books were poorly organized, both at the scale of the shelf, where books on specific topics should have stood side by side, and by room, where at least some common thread should had linked all the books within. He sought to discover an order among these new books but ultimately decided that the only commonality was likely that each had been read at some point in his life by the insurance clerk. Of course this seemed a less than ideal manner of organization to the librarian.

Still, there were several books on topics not previously contained within the library, making this unexpected addition not a total loss. For example, there was a book titled, “Heirlooms of the Anxo Family”, which spanned millennia, from myth to modern times, and detailed the introduction of angelic blood into the family estate. On a related note, there were several texts describing various aspects of mortal men descended from angels. The librarian paid special attention to one titled, “On the Neuroses of the Angel-Blooded”. The author of this tome was insistent that the presence of an angelic lineage was not a panacea for all ills. On the contrary, it gave rise to conditions not found outside this select group. For example, the layman might well imagine that a small dose of transcendent spirituality lingering within one’s cells might prove advantageous in many occasions. Would it not be delightful to have at one’s disposal an inexplicable reserve of joy to ward off bouts of worldly despair? Would it not prove beneficial to rely on some intrinsic though divine charisma to persuade others to one’s point of view? Each of us can likely imagine many instances in our own lives where a healthy dose of irrepressible faith in the goodness of the universe might have made circumstances turn out for the better. However, the author of “On the Neuroses of the Angel-Blooded” suggested that having a bit of angelic heritage spliced within one’s genome gave rise not (at least exclusively) to manifestations of joy. There were documented instances where the foreign presence was treated as a viral trespasser, unable to be assimilated into the healthy functioning of the body. To intuitively sense at all times that there was a portion of one’s being, which was simply superior to the crude matter of the rest of the body surrounding it, was not, it seems, invariably reassuring. One could sense in a single being the potential for perfection and the manifestation of a reality that fell immeasurably short of it. There existed a temptation for one of an introspective nature to succumb to a preoccupation with the inconsistencies within one’s self and to exclaim in solitude, “Oh Lord, what purpose in the making of one such as me!”

If you, Gentle Reader, have had opportunity to make such an exclamation yourself, then you might come to the same conclusion as did Hong Samud, namely that the instances of angelic blood within the lines of mortal men are not so rare as we have been led to believe.

|

|

|

|

|

September 9, 2015

On the Many Entrances to the Library

Once Hong Samud came to the realization that the doorway to each and every room in the library served a second purpose, namely as a portal to a separate library in a distant land, he was faced with a dilemma. He pondered whether he had an obligation to investigate the destination behind each doorway. The argument against exploration rested on the empirical fact that he had existed in a satisfactory state for one thousand years in this library none the wiser to the duplicity of the entrances. The argument for further exploration was nurtured by his reservations that the library had a greater purpose to fulfill than that which it currently served.

“Maybe, I will try just one door,” he said to himself. “But which one?” It mattered not since the destinations of all but the one through which the insurance clerk had led him were a mystery to him. Eventually, succumbing to a combination of curiosity, duty and unfounded hope, Hong Samud selected the door to room 651.

He slid the yellow paper card along the wooden frame of the entrance. He stepped through the doorway.

He knew that his experiment had been successful (there had been little doubt that it would be) because as soon as he arrived in the distant library, a bevy of impressions assaulted his senses. Taken together his senses convey incontrovertibly to him that he had made an egregious mistake. Individually, the elements of this observation included a strong and unpleasant smell of chemicals, as if the leather in which the tomes were bound had been rendered from hides in vats located in the basement of the library, from which fumes had filled the edifice. In the cold, dry air, the stench seemed to linger in Hong Samud’s lungs, accumulating with each breath. He would not stay long. The library itself was poorly lit; a weak, sickly light emanated from gas lamps placed at the intersections of aisles and halls. Perversely, these lamps were shaded by panes of black glass, which contrary to their intended purpose, allowed only a fragment of their light to escape. The shelves that lined the aisles were formed of an ebony wood. In a manner that was simply at odds with both utilitarian design and safety, all edges of each shelf were ornately carved into a series of sharp spikes. One had to be very careful in removing a book lest one puncture a hand or slice the underside of a forearm in the process. Although one naturally expected silence in a library, the silence which Hong Samud encountered seemed to possess an unwholesome nature, as if it had resulted from gruesome measures.

More than can be conveyed by any physical senses, the library communicated to Hong Samud a smothering sensation of dread. To be sure, Hong Samud had never imagined much less visited a library like the one in which he now stood.

In order to make absolutely certain that he could return to the sanctuary of his own library, Hong Samud’s first action was to turn and examine the portal through which he had traveled. He found a passage cut into a stone wall, surrounded by an engraving of a gargoyle, with its head centered at the pointed top of the doorway and its simian arms draped down either side. He had little trouble in committing the appearance of this door to memory, as well as its relation to any other markers, the gas lamps and the aisles themselves, for, knowing well the labyrinthine nature of libraries, he did not want to become lost.

In an attempt to identify his location, Hong Samud very carefully removed one book from the closest shelf. The book was bound in black leather. No title was printed on the spine nor the front cover. He cautiously opened the book, seeking the imprint on the interior of the front cover that would, according to the customs of librarians, identify the library to which the book belonged. Hong Samud was not disappointed for he found exactly the information that he had hoped to find. Pressed into the board and filled with a blood red ink was the insignia of a horned and leering face around which in script was written,

Property of the Normal University of Hell, Phlegethon Campus

As he stood almost paralyzed, though less by fear than by fascination, numerous thoughts flooded through Hong Samud’s mind. We note but a few of them. ‘So they have libraries in Hell,’ thought the academician in him. ‘There is terrible danger here. I had better leave immediately,’ suggested that portion of him committed to the pursuit of common sense. ‘I may never have another chance like this. What harm is there in looking through a book or two? What’s the worst that could happen? I’m standing right next to the exit. I’ll be able to leave in an instant if there is trouble,” argued the librarian with himself. A flurry of other thoughts simultaneously struck the librarian, as, holding the book in one hand, he flipped to the title page of the book and discovered, “On Punishments Particular to Librarians”, a topic of some natural interest to him.

If the title of the book set the trap, the table of contents sprung it. Hong Samud stood transfixed as he scanned the list of chapters, which began with the following entries

| Chapter 1. Torments of Librarians Who by Design Damage Books |

1 |

| Chapter 2. Torments of Librarians Who through Neglect Damage Books |

157 |

| Chapter 3. Torments of Librarians Who Fail to Maintain Catalog Ordering |

234 |

| Chapter 4. Torments of Librarians Who Fail to Maintain Proper Silence |

299 |

| Chapter 5. Torments of Librarians Who Bear False Witness Regarding Availability of Books |

367 |

| Chapter 6. Torments of Librarians Who Steal Books from Their own Library |

422 |

| Chapter 7. Torments of Librarians Who Steal Books from Other Libraries |

487 |

| Chapter 8. Torments of Librarians Who Covet the Books of Other Libraries |

505 |

| Chapter 9. Torments of Librarians Who Covet the Librarians of Other Libraries |

596 |

| Chapter 10. Torments of Librarians Who Murder Other Librarians |

638 |

| Chapter 11. Torments of Librarians Who Murder Patrons |

671 |

Hong Samud read the full page and flipped through several more pages of contents, until his eyes fell upon a peculiar entry and remained glued there.

| Chapter 651. Torments of Librarians Who Invade the Libraries of Hell |

4432 |

‘How apropos,’ Hong Samud thought to himself even as his skin began to crawl. He noted the page and hastily turned to it. So engrossed did he become in subject matter presented in that chapter that he utterly failed to hear the footsteps of the floor librarian as she investigated the flutter of pages that disturbed her orders for an inviolate silence.

This librarian, like all librarians in Hell, was a devil chosen for those attributes that made her particularly well suited to the role. Like Hong Samud, she prized the company of books over that of patrons. However, quite unlike Hong Samud, she reveled in the misfortune of others. As she turned the corner and found the trespasser huddled over one of her precious books, the leathery wings that rose from her back passed in front of the gas lamp and cast a shadow over the page, which Hong Samud read.

She allowed him the leisure of lifting his head slowly from the book, so that she might relish the terror that filled him as he beheld her diabolic visage. She luxuriated in his panic even as she eyed the quality of his skin, which she intended to drag to the cellar and transform into a leather binding for a sentient book titled, “The Calamitous Error of Hong Samud”. Then she lurched forward, screaming down the aisle toward him. Her wings flapped uncontrollably in the confined space, catching on the sharp spikes that protruded from every shelf. Tiny fragments of black, bloody pulp were thrown up in the air as she tore toward him, arms outstretched, claws seeking flesh.

Hong Samud knew librarians well. Instinctively, he threw the book he had been holding into the air. It provided only a momentary distraction in which the devil had to decide whether to catch the book, saving it from the damage of the fall, or grab the intruder. Since she did not suspect that there was a ready means of escape available to the intruder, she grabbed at the book. In this instant, Hong Samud frantically swiped at the stone archway with his library card and leapt through the portal.

He landed on the familiar stone tiles of his library, lost his balance and fell hard, bruising his hip. The sound of the screeching devil was abruptly cut-off as the portal closed but the chemical stench of the library clung to his clothes and the inside of his mouth. It took a moment to notice that his heart was pounding. Even the observations that the portal was gone and that the devil seemed not to immediately be able to follow did little to settle his nerves.

Hong Samud remained where he had fallen for some time, nursing the pain in his hip and absorbing the comforting silence of his library. He tried to make sense of some reason that his otherwise perfect library should be intimately connected to Hell, but none came to him. Eventually he rubbed his face with his hands, only to discover flecks of the pulp of the shredded wings of a devil stuck to his forehead and cheeks.

Later some scholars would say that a doom hung over Hong Samud. Some would even cite this instance as a baptism in the blood of Hell through which he had been consecrated to this doom. Other scholars would argue that, on the contrary, Hong Samud’s fate was sealed at the moment of his conception when the curious sequence of chromosomes were assembled, which would, in time, compel him to create a perfect library, existing outside the time and space of reality, indiscriminately connected to libraries that spanned realms lying inside and outside the established boundaries of belief.

|

|

|

|

|

September 10, 2015

On the Exits from the Library

In time past, Hong Samud had occasion to leave the library, invariably in search of new books. He had returned without exception to the physics-based reality of his birth. The passage between one reality and the other was accomplished as easily as slipping in and out of a daydream. To arrive in the library, Hong Samud had only to find a comfortable position, close his eyes and imagine himself in the company of his books. As many schoolchildren can attest, as is the case with daydreams, sometimes he inadvertently slipped into the library, carried away by a passing fancy.

To depart from the library required much the same exercise. Again, as with daydreams, frequently the exit from the library occurred with a jarring start, after which Hong Samud looked up, bemused, to find the circumstances of a reality populated by billions of souls once again pressing in upon him on all sides.

A peculiar state of affairs arose, for which we have no plausible explanation, after Hong Samud was issued his library card. It seemed that, having discovered a methodical way to enter and leave the library via portals to other libraries, he had lost the knack for the simple, intuitive manner in which he had previously gained access to and egress from his library. We present this as fact and offer only the following analogy by way of explanation. Reason, powered by logic and empiricism, routinely demonstrates the ability to rob one of wonder. A phenomenon, once a source of marvel, may lose its appeal once the physical mechanism by which it arises is revealed. Take, for example, the moon, red on the horizon, lightening to orange as it rises, then becoming yellow still higher before claiming its lustrous white at an apex above us. Many who stay out past dark in urban locales and are inclined to gaze skyward have remarked on the beauty of this lunar transformation. Yet, when it is revealed that it is anthropogenic pollutants released into the atmosphere, which are responsible for this spectrum of color, we no longer see the celebratory nature of the moon. Instead, we have lost the sense of awe and observe this ascension only as a struggle to doff a dirty shroud discarded carelessly in its path. So it appeared with Hong Samud. Once he held the library card, he could no longer access at will the physics-based reality, which had once been his home.

Hong Samud discovered this unpleasant loss shortly after his escape from the library of the Normal University of Hell, Phlegethon Campus. Shaken by the closeness of the attack and his inexplicable lowering of his guard in the pernicious environs of Hell, he had sought relief outside the library. He had sought, if only in a moment of weakness, the comfort of home. Perhaps, he thought, he might even visit his elderly mother. At first he attributed his inability to leave the library as a case of nerves. He was clearly more disturbed than he wanted to admit to himself. However, as the days passed and each subsequent attempt ended in failure, Hong Samud began to look at the library card with suspicion, if not irritation.

It was preposterous to think of the library as a prison for it had an infinite number of exits spaced at regular intervals along its length. Still, Hong Samud felt trapped. The doors were untrustworthy. Perhaps many portals led to Hell, or similarly hellish realms. He entertained the logical thought that at least one doorway likely led to a library in the physics-based reality of his home, but he did not know which one. He liked to think that it was the doorway to room number one, but was unwilling to test this hypothesis so soon after his narrow escape from Hell. The only other safe alternative was room number 3,172, through which the insurance clerk had arrived and departed.

Thus it was through this doorway that Hong Samud departed, carrying with him a thought that he had never harbored before, namely the curious idea that he needed a respite, however brief, from the confines of his library.

|

|

|

|

|

September 11, 2015

On a Reprieve from the Library

Within the library of Hong Samud, neither the sun nor the moon appeared to mark the hour of the day. One may wonder then as to how the library was illuminated in order that the books might be read. An arrangement had been struck that fell somewhere between the realms of physical chemistry with its unyielding laws of thermodynamics and the elusive fancy of perpetual motion machines. The molecules in the air within the library vibrated in such a way that electrons were elevated to excited states, according to established physical mechanisms. From there, the electrons fell back to their more stable state through a variety of light-emitting processes known as fluorescence or phosphorescence among others. Once released, the photons of light struck other molecules, inducing in them similar phenomena, resulting in a sustained source of light. The only riddle that might cause one knowledgeable in such fields to protest was the manner in which this light skirted the inescapable inefficiencies that would cause the intensity to gradually diminish over time. Here, the limits of our own knowledge are exceeded. A scientist more clever than us might concoct a theory that the stone tiles of the floor had been embedded with ordered arrays of photocatalytic nanoparticles that absorbed the ordinary bombardment of background cosmic radiation and downshifted it toward frequencies that more readily interacted with the molecules in air. Speculative digressions aside, the light of the library came from within its own atmosphere, illuminating without shadow.

The absence of sun and moon had a second effect; Hong Samud never knew what time it was. There were no clocks of any kind in the library. In fact, time was a largely irrelevant concept in his library. As such, when he left the library through the portal leading to room 3,172, he arrived in the other library in the darkness of midnight. Although he had visited once before, he found it hard to retrace his steps from memory. He stumbled repeatedly trying to make his way to the stairs. He knocked over two chairs in the process.

He carefully descended the stairwell in darkness. On the first floor, a streetlight cast some glow through the glass doors of the front entrance. By this meager light, Hong Samud navigated past the reading tables and the front desk to the entrance, where he found to his dismay that the doors were locked.

“It’s quite understandable,” he said to himself, “Any librarian worth his salt would protect the treasures that lie within.” He said this as much to justify his over-protectiveness of his own library as to offer comfort to his current predicament.

He jerked several times at the door, hoping to jar it loose, but to no effect. The door rattled and the small brass bell attached to it rang several times in protest.

The commotion, as minor as it was, proved sufficient to reach the ears of the night deputy from the constable’s office, whose duty it was to patrol the city during the hours when most of its citizens were fast asleep. The deputy, a young man highly regarded for his compassionate approach to his sometimes unpleasant duties, unlocked the door and interrogated Hong Samud by streetlight on the front lawn of the library.

“What are you doing in the library at this hour?” he asked.

“I’m a librarian,” said Hong Samud, truthfully.

“You don’t look like you are from around here,” said the deputy, who was fairly certain that he knew all of municipal employees, including the librarians, in this small town. Certainly, he had never encountered this small, swarthy man.

“I have a library card,” Hong Samud said in his defense, brandishing the yellow sheet of paper.

“What’s your name?” asked the deputy.

Hong Samud experienced a premonition that things were going to turn out poorly if he didn’t gather himself and present himself in a better light.

With a surprising dexterity, the deputy plucked the card right out of Hong Samud’s waving hand. “Hong Samud,” read the deputy from the card.

“Yes,” the librarian agreed. “That is my name.”

“I’m going to ask you one more time,” warned the deputy in a patient tone, “before I take you to the station, what were you doing in the library in the middle of the night?”

“I was trying to get out,” Hong Samud answered honestly.

Unfortunately, the reply struck the deputy as flippant. He gently but forcefully escorted a silent Hong Samud to the police station. There Hong Samud was booked by a second clerk in an otherwise empty building for trespassing on municipal property.

“It’s a fifty dollar fine,” said the clerk. “If you pay it you can go.”

Hong Samud carried no currency of any kind on his person. He had abandoned the concept of currency a thousand years ago. He opted not to share this information. Thinking (at least partially correctly) that Hong Samud was a vagrant with no place to spend the night in town, they put him in one of two jail cells.

It turned out that it was Saturday night. Several hours passed before a pair of rowdy drunks was deposited by the same deputy to sleep off their stupor in the cell opposite Hong Samud. From behind iron bars, these two men shouted various inane comments at Hong Samud, mostly asking for his agreement regarding the indignity of their common incarceration.

Hong Samud sat on a wooden bench and kept his eyes closed. In the old days, he would simply have returned to the library via his daydreams. However, having lost not only that power but having had his library card confiscated, he presently had no means to access the library. He had some time to rue his errors. Sunday was a holy day; while the drunks were released on their own recognizance on the following morning, the courts would not deal with him until Monday.

|

|

|

|

|

September 14, 2015

On the Rescue of the Librarian

Monday morning found Hong Samud seated in a room that occasionally served as a side-chamber where the local judge could meet with the prosecutor and defense attorney outside the adjacent courtroom. Paneled in wood, hung with portraits of long dead citizens of note, this room seemed well suited to deciding the fates of men. On this instance, it was not put to such a grand purpose. Instead, Hong Samud was seated in an upholstered chair at a desk, behind which he was eventually joined by a woman who identified herself as a multipurpose employee of the court. She left the door to the room open, as the town did not employ a sufficient number of deputies to assign one to Hong Samud for the duration of his activities this morning. A steady stream of foot traffic passed through the hallway.

Hong Samud searched the woman’s face for a trace of compassion but found it largely hidden behind an impatience born of an anticipation of a myriad of tasks, some known and others not yet revealed, which would consume her attention as the day progressed. He explained to her that he had the greatest respect for libraries. He would never think of stealing a book from a library or damaging the precious contents within. In fact, he had reason to believe that there were special punishments reserved in Hell for librarians who committed each of those crimes.

At this last declaration, the court clerk jotted a note on her pad of paper, then lifted it to an angle where her writing was hidden from the eyes of Hong Samud.

She next placed a folder over the pad and opened it. From it she withdrew a form and Hong Samud’s temporary library card.

“Why have you come to this town, Hong Samud?”

Hong Samud closed his eyes and asked himself the same question. He had come because the insurance clerk, in giving him that canary-colored card, had somehow robbed him of his ability to leave the library by ordinary means and he did not know which doors were safe and the devil had scared him and his beloved library closed in about him like a prison and he needed some air. This was the truth. Hong Samud was a great believer in the truth. He inveterately believed in the maxim that ‘we must never lie or we shall lose our souls’. However, on this Monday morning, Hong Samud eschewed the truth. In his fear, he did not believe that the truth would set him free from this bureaucrat and her procedures.

He glanced up at her to ascertain if a change had come over her as he ruminated. He found only a growing impatience. “Forgive me,” he pleaded, “I am seeking the right words.”

“We haven’t got all day.” She released a slow, exasperated sigh for she believed this man, who appeared to be indigent despite the fact that he was well-spoken, well-groomed and wore clean clothes, had no better plan than to waste the good hours of what could have been a productive morning.

Hong Samud took a deep breath and resorted to an alternate truth. “I came to see Monsieur Anxo of the Sigil Insurance Company.”

The court clerk had not expected those words. Had this information been communicated earlier, there might have been no need to leave the vagrant in the cell all weekend. “In what capacity do you know M. Anxo?”

Again Hong Samud found it necessary to carefully choose his words. “I have helped him, in the past, acquire information relevant to his calculations.”

“You are a business associate?” said the court clerk, raising an eyebrow.

“Of a sort,” Hong Samud agreed weakly.

The court clerk seemed to brighten. If she could get Anxo to pay the fine, she could be rid of this perplexing nuisance.

Hong Samud was curtly returned to his cell. Approximately an hour and a half later, a deputy retrieved him and led him to the lobby of the constable’s station, where, holding the same folder that the court clerk had kept earlier, M. Anxo stood. Upon the arrival of Hong Samud, the insurance clerk examined the librarian with a searching expression, largely attempting to rationalize to himself why in the world he had agreed to get himself mixed up in the affairs of a crazy old coot who fancied himself a librarian.

|

|

|

|

|

September 15, 2015

On Charity toward Librarians

The two men stood outside the constable’s station. The sun was nearing noon in a clear sky. “They told me that you didn’t eat,” said Anxo.

“I am a vegetarian,” Hong Samud replied. He had not been sure that the prison fare would have agreed with him. Besides, he hadn’t eaten in over a thousand years. What difference would another couple days make? He neglected to mention this last bit to the insurance clerk.

For his part, Anxo also kept much of their conversation to himself, for he too was a vegetarian but he did not want to reinforce any more common bonds with the librarian than was absolutely necessary. Instead he led him to a sidewalk cafe, where he treated him to flat bread with hummus and a plate of fresh fruit.

Hong Samud ate eagerly. The grapes, peach and apple tasted uncommonly good to him, although he could not decide whether it was because he had not eaten in so long or rather because he had just been released from jail and the food tasted of freedom.

Anxo, on the other hand, picked at a slice of peach absent-mindedly. He had soon to return to the office, though his manners forbade him from mentioning this to the librarian, lest he take it as an implied order to hurry.

“What were you doing in the library?” asked Anxo, when Hong Samud was between bites, wiping his face with a white, cloth napkin.

Hong Samud raised his eyes from the plate to the face of the insurance clerk. Again, he searched for a receptivity to the information that would truthfully answer this question. Again, he found only the hints of an impatience; this man too found him only a bothersome delay to more pressing events. But, Hong Samud reminded himself, he was impressively polite about it.

“I didn’t realize,” said Hong Samud, “that the library would be closed.”

“In the middle of the night?” countered Anxo in a skeptical tone.

“I lost track of time,” Hong Samud admitted. He desperately wanted to share with this man, descended from angels, the impulse that had driven him from the library, but he could predict all too well that his words were not welcome. Although Hong Samud dearly cherished truth and he also believed that transparent communication was an apt remedy for a great many ills, he betrayed both these principles and remained silent.

For this reticence, the insurance clerk was grateful. He had nearly reached the limits of his charity. When Hong Samud was finished with the meal, Anxo rose and paid. On the sidewalk he bid Hong Samud farewell and turned to go, but was interrupted by the librarian motioning to the folder he still carried.

“I will need my library card,” said Hong Samud.

“I don’t know if that is for the best,” said Anxo. “Perhaps, you should steer clear of the Tower Library for a while.”

“How will I get home?” asked Hong Samud.

“I’m afraid I don’t know what you mean.” Whatever difficulty Anxo encountered in the literal interpretation of the librarian’s words, he clearly read the agonized expression on his face. He opened the folder and surrendered the temporary library card; it seemed to mean so much to the man.

“I am in your debt,” said the librarian.

“Think nothing of it,” replied Anxo, who desired no connection to remain between them.

“When you are in need of my services again,” said Hong Samud, “I shall consider it an insult if you do not call upon me.”

“There is no need to feel so aggrieved,” promised the insurance clerk, allowing the circumstances of the moment to outweigh his better judgment. “I will do as you request.”

They parted ways. Hong Samud had no other destination than the library. He had seen enough of this town from the interior of one of its two jail cells. He had no idea where the library was located relative to this cafe though he had dared not ask the insurance clerk for fear of alarming him. Instead, Hong Samud wandered through the small town until he came across a street sign for Maple Avenue. He seemed to recall having seen such a sign near the library.

While standing at the intersection, he stopped a pedestrian and asked, “Which way is the Tower Library.”

Without breaking stride, the pedestrian pointed left.

Hong Samud followed this direction and after perhaps a dozen blocks arrived at the library. He entered and immediately became the intense focus of the two librarians at the front desk. Clearly, the word of a stranger stumbling about the library on Saturday night had been shared with the librarians and they recognized him as the culprit.

Hong Samud nodded in greeting. He thought it a bad time to request the permanent copy of his library card and instead opted to stride past the desk and up the flight of stairs to the Special Collections wing. There, he glanced over his shoulder and, finding himself alone on the second floor, swiped the door and returned to his library.

He did well to leave quickly for the librarians summoned the deputy, who found no sign of Hong Samud. After the library closed, the deputy returned and alongside the librarians, they searched every nook and cranny. When they had exhausted all possible hiding spots, they were forced to accept that the trespasser must have slipped out of the library unnoticed, though none felt very convinced of this conclusion.

|

|

|

|

|

September 16, 2015

On an Excised Digression

Nestled in the haven of his library, Hong Samud, true to his introspective nature, contemplated recent events—the arrival of an unexpected patron, the unintended excursion into Hell, and his deflating visit to M. Anxo. In the timeless environment of this archive, Hong Samud felt no pressure to examine his thoughts with alacrity. Instead, he methodically scrutinized the sequence of events, allowing what were at best peripheral digressions to occupy a majority of his interest. He sought meaning in minutiae and reprimanded himself for what, in retrospect, he judged to be poor decisions. He often found comfort in his fellow denizens of the library, breaking its silence only with the whisper of the turning of stiff, ancient pages. Through this glacial movement of thought, he allowed the tension, which had come to fill him, to drain away until he thought himself returned to the equilibrium of his normal, passive state.

Gentle Reader, we will not recount in full the details of the passage taken by the librarian through his ruminations, an account which even the most dedicated reader can be expected to have little sustained interest. Instead, we shall allow this brief soliloquy to suffice. It is impossible to state, without external reference, the number of months or years that transpired during this equilibration process.

In past works, when faced with a contemplative episode such as the one in which Hong Samud was now immersed, the author of this work saw fit to commit to writing in its entirety the sequence of thoughts that passed through the protagonist’s mind. Sometimes, these lengthy digressions were included in the text of the chapter itself. On occasion, special appendices were attached to the text to be referenced by the unusually devoted reader. In this case, for better or worse, no such accommodations have been made. It is not even clear if the author explicitly described each link in the chain of Hong Samud’s thoughts. If such passages do indeed exist, they have been entirely excised from this version of the tale. Regardless, we have arrived quickly at the end of this digression, having provided a satisfactorily brief but necessary explanation as to why, after his unpleasant if not harrowing encounters through door 651 and door 3,172, Hong Samud reconciled himself to the opening of another door.

|

|

|

|

|

September 17, 2015

On Ornithological Libraries

Hong Samud reasoned that the doorway to the first room, room 1, would lead him back to a library in the physics-based reality from which he originally hailed. Moreover, he suspected that it would return him specifically to one of two libraries—either the library of his hometown, where much of his childhood summers had been spent, or the university library, inside which much of his professional life had transpired. He was wrong on all counts.

When he had gathered his courage and swiped at the doorway with the temporary library card, the portal opened and he stepped through into what he initially took to be an aviary. He had never considered the interpretation of zoological institutions as libraries, but faced with this destination, he now readily accepted it. This aviary was a living repository of ornithological knowledge, or so he supposed.

From the general, his thoughts quickly turned to an inspection of the particulars. First, he turned and examined the portal from which he had arrived, for if there proved, once again, to be need for a hasty departure, he wanted no trouble in identifying his point of origin. To his surprise, Hong Samud discovered an arched doorway, in which the sides of the portal were formed by the sizeable trunks of two, mature sycamore trees and the top formed by the meeting of branches from each tree. It was difficult to see more, for he had arrived at what appeared to him as a twilight hour, and the darkness limited his vision. In fact, the sense of an aviary came not from his sense of sight for he saw not a single bird, but rather from the cacophony of bird song that greeted him.

The calls of many dozens of species of birds rang out simultaneously. To the untrained ear, it was indeed cacophonic, for the resulting barrage lacked melody, harmony or steady rhythm. Despite the obvious absence of musical form, it took little effort from Hong Samud to imagine that the sonic tapestry was ordered according to a structure that, due to his unfamiliarity with the subject, eluded him.

He stood for some time beneath the shadowed canopy of broad leaves, allowing the frequency of his biological processes, breathing and pulse, to acclimate to the erratic patterns of the song. During this time, Hong Samud decided that he likely was not confined within a fixed enclosure, for this space bore the unmistakable aroma of open woodland and expanses of forest.

No native librarian, or ornithologist as the case may be, emerged from the surrounding trees to greet Hong Samud. Keeping to a straight line, Hong Samud walked from the now closed portal a dozen paces until he emerged from beneath the canopy into a small clearing. From this vantage point, he looked up and observed that his estimate of the time of day had been in error. The sky was tinged with violet, but not from a rising or setting sun. Instead, a dense expanse of stars filled the firmament. The constellations were entirely foreign to Hong Samud and the stars shown more clearly their natural colors of red, yellow and blue. Between the points of light, interstellar dust had collected, which appeared to be the source of the violet hue that cloaked this forest. Like a frog at the bottom of the well, Hong Samud had a limited view of the heavens. His window was framed by the leafy contours of trees, which in the peculiar light were cast in black silhouette.

Hong Samud doubted that any such place on his native planet gave rise to such a view. He therefore entertained the notion that he had entered a library on another planet located in a distant galaxy or perhaps an alternate universe altogether. We can accept that such admissions came readily to Hong Samud, who had already established that one doorway from his library led to the unlikely destination of Hell.

He moved to the middle of the clearing, in order to be surrounded on all sides by a rough symmetry of trees and an alien nebula above, so that he might be better permeated by the lore of a thousand singing books. In this midst of this performance, Hong Samud was overcome by a sensation of drowsiness, which crept upon him stealthily then pounced abruptly. Despite his attempts at vigilance, he lay down on the mat of clover and wild strawberry and promptly fell into a deep slumber.

|

|

|

|

|

September 18, 2015

On the Other Librarian

In order to reduce the energy required for flight, birds evolved a light skeletal system, possessing thin, hollow bones. Because homo sapiens only dream of flight, the evolutionary process has resulted in a broader distribution of bone sizes in that species. Consequently, terms such as fine-boned and big boned have entered our vocabulary.

The librarian, who observed Hong Samud from a hidden vantage point, unquestionably displayed the petite, fine-boned structure of song birds, but there was arguably very little else delicate about her. She appeared in a child-like form, a foot shorter than Hong Samud, though, despite his thousand years, she was far older; her origin stretched back into communal myth.

She wore a black ankle-length, long-sleeved dress with a shawl cut from the same, thin fabric wrapped around her shoulders. Any iridescent sheen was only an illusion of the violet starlight in which the forest was cloaked. Very little of her flesh was exposed: her bare feet below the ankles, her hands beyond the wrists, her face above the stiff collar at her neck. Having been exposed only to a pervasive, dim light, her complexion remained pale. To note that her hair was unkempt is an understatement for that unruly mass spread out and hung down past her shoulders in long, stiff bundles as if made of a flat black straw. Adding even further chaotic structure to this hair were the many feathers, one would guess donated by a crow, which were woven into her hair at haphazard angles.

With the bones of a bird and the feathers of a crow, we shall call this other librarian the crow girl. It suited her well and matched the steady, black gaze of a crow with which she followed the movements of Hong Samud as he milled about in her library.

Those readers already familiar with tales of the crow girl will duly note in this description the absence of the black, feathered wings sprouting from her shoulder-blades, enlarged to a scale able to generate sufficient force to loft her in the air. Not for the first time then will we refer to glamour, a sort of illusory skill, designed to hide the extraordinary among the ordinary. The term glamour derives from grammar, or scholarship, when applied to subjects of the occult. It is often invoked to describe the means by which we are oblivious to the passage of supernatural creatures in our physic-based reality. It is also appropriately although infrequently applied in a more mundane sense to describe extraordinary humans who hide themselves among us. Here I specifically think of brilliant children, who hide their brilliance, in order to better fit in with their peers. Digressions aside, we found no sign of wings in our examination of the crow girl.

What remains to be presented in terms of the physical appearance of the crow girl are the contours of her face and the expression carried upon it. Although we have waited impatiently for the opportunity to commit this face to writing and we poorly contain our desire to introduce her, we shall postpone that pleasure until she presents herself to Hong Samud, at which time we shall allow him to describe her in his own words.

|

|

|

|

|

September 21, 2015

On the Meeting of Two Librarians

By the time Hong Samud noticed a shadowy form approaching the clearing along an unseen path leading deep into the trees, he had become completely disoriented by the song of the books in this library. Thinking of the librarian in Hell, he panicked. He lurched to one side only to find that every gap between two trees along that edge of the clearing resembled an arched, arboreal portal. A quick glance to the other side assured him things were much the same there as well. Like a deer trapped in a floodlight, Hong Samud stood frozen. He regained his composure only when he resigned himself to his fate. He straightened his shirt and waited for the form to enter the clearing and come to stop ten feet from him. The song of the books lowered in volume at her arrival, but did not entirely succumb to silence.

“Welcome,” said the crow girl, “to Librum de Avibus.”

Hong Samud took a step closer, to better observe the speaker in the dim light. The voice was that of a young girl, perhaps twelve, who had only recently begun the passage into womanhood. For a moment, she cocked her head at an angle and fixed him with a steady gaze, a posture at odds for a girl, but natural to a bird. Hong Samud drew closer. Even at a distance of a few feet, the girl’s expression remained inscrutable. Her pallid complexion reflected star light and betrayed the same reticence as star light, in which one knows it to be ancient and full of memory and yet it refuses to yield its secrets. The pupils of her eyes seemed as black as the irises, the sclera too white in contrast. Although we might expect it to be hooked like a beak, her nose was nearly as flat as that of Hong Samud and her thin lips the color of peach.

Hong Samud recognized in the expression of this creature a librarian, who displayed a protective stance for her charges, a role born either of a strength of will or an utter disregard for those tribulations that would, in others, require strength of will. Although it was a rhetorical question, he asked all the same, “You are the librarian?”

“I am,” replied the crow girl.

“You have a lovely library,” said Hong Samud, gesturing to the trees from which the voices of the books had come.

“Thank you,” said the crow girl formally.

“I too am a librarian,” said Hong Samud, still unable to read the girl, and hoping to establish some common bond, for he had yet to entirely rid himself of the fear that this creature of fair appearance might abruptly snap her fingers, causing a tangled murder of crows to hastily materialize, which would promptly peck him clean to the bone.

“Yes,” agreed the crow girl, accepting their common roles. “I have been waiting for you.”

Despite the fact that most of us would agree that it is always good to feel welcomed, these words set Hong Samud on edge, for, to his knowledge, he had given no prior notice of his intention to visit. In an attempt to appear as nimble as the crow girl, Hong Samud therefore replied, “You are precisely as I had imagined.”

Perhaps the flicker of a smile passed across the crow girl’s face. She admitted, “I had imagined you might be younger.”

Hong Samud laughed despite his uncertain surroundings. His high laughter caught in the trees around him. A chitter of peer-ips and too-whits erupted in response.

All in all, the meeting of the two librarians, which could have played out in an infinity of ways, many of them unfortunate, transpired in a manner acceptable to both parties.

|

|

|

|

|

September 22, 2015

On an Agreement between Librarians

“Presumably,” said the crow girl, “you have come to my library, not just to listen to the books, but to seek some particular information.”

“Of course,” agreed Hong Samud. His eyes shifted from her face to the matted mass of hair lying against her shoulders. If he had intended to say more, he seemed to have lost his train of thought.

“How may I help you?” asked the crow girl.

Hong Samud stared at his feet then described to the other librarian his dilemma in the following words. “There seem to be a virtually infinite number of entrances to my library, with more appearing each day.” He glanced up at the face of the crow girl but found only an implacable expression. “The problem is, I don’t know where they all go. In fact, I only know where three of them go and one of them is here and I only know that because I stepped through it and here I am. But I should not like to go someplace uninvited where I am not welcome and my reception may be far less pleasant than the one you have extended to me.” Here he thought of his greeting by the diabolical librarian in Hell. He left the rest of his request unstated. It seemed more or less obvious to him.

The crow girl considered his request for several minutes beneath the violet star light. “Although some of my atlases and books on cartography do contain maps of historic libraries, I am afraid that your library is not among them.”

Hong Samud had not imagined that someone might have mapped out his library without his knowledge. He was quite relieved to discover that no such document existed in this library and fervently hoped that the same was true of all other libraries.

Hong Samud hid his expressions much less capably than the crow girl; she followed his train of thought with ease. She added, “Nor can I provide a recipe for knowing the destination of a single doorway, much less an infinity of them, simply by idle speculation.”

“Of course not,” said Hong Samud, admitting the patent unfeasibility of his request.

“I would have to inspect them personally,” said the crow girl, surprising Hong Samud.

Hong Samud considered the presence of the crow girl in his library and was not altogether taken with the idea. She might map it and commit the description to one of her books. “Oh,” he replied, “There is no need for you to go such great trouble. I did not mean to impose upon you in this way.”

The crow girl understood his reservations perfectly well, but she did not lay his insecurities to rest. Instead she announced, “I shall help you, on one condition.”

“Yes?” asked Hong Samud, tentatively. “What is your condition?”

What emerged next from the crow girl Hong Samud would not have occurred to Hong Samud had he been given the next million years to imagine her words.

“That you allow me to call you Agidoda, which means ‘my father’ and that you call me Uwetsiageyv, which means ‘daughter’.”

Hong Samud allowed the star light to bathe over him in the silence that followed. “Ew-way-chee-ah-gay-yun?” said the librarian, stumbling over the unfamiliar sequence of syllables. “But you are not my daughter,” he protested, though he rightly now understood that he had entered upon a path over which he had surrendered much of his control (or his illusion of control, if you prefer).

“That is my condition all the same,” said the crow girl.

“This is all so sudden,” said Hong Samud. “I feel I haven’t given any thought to the sort of daughter I would like to have.” No truer words had Hong Samud ever spoken.

“Never mind that,” she said, “were I to arrive as your biological daughter, you would have no more say in the matter.”

The librarian stood quietly, his eyes cast to the forest floor. His eyes traveled along the leaves of wild strawberries, to the girl’s pale, bare feet.

“Do you submit to this binding?” asked the crow girl.

“Yes,” said Hong Samud with a degree of solemnity, for he was a man who took oaths with the greatest of seriousness, “I so submit.”

Because Hong Samud had totally lost his bearings, he allowed the crow girl to lead him to the portal from which he had emerged. With a half-hearted wave of his library card, the portal defiantly opened.

Saying, “After you, Agidoda,” the crow girl followed Hong Samud back to his library.

|

|

|

|

|

September 23, 2015

On a Tour of the Library

The crow girl obediently followed Hong Samud as he conducted the tour around and around the loops of the spiraling central corridor, which never rose nor fell and yet continuously led to new rooms. If the deviations from Euclidean geometry perturbed her, she did not allow it to show. The stone tiles felt uncomfortably cold on her bare feet, though it seemed that Hong Samud had made no arrangements for personal comfort, neither his own nor that of anyone else, so she kept quiet on the matter for the time being. The walls of the central hall were also constructed of stone, a pale gray giving way to patches of brown, though they were not cut in tiles, and had been worked only to a state where the practiced strokes of the chisel were more apparent to fingertips than to the eye. Inside any one of the rooms, the composition of the floor did not change, although the walls were now lined with wooden books shelves, cut from a hardwood, perhaps maple, and stained to a deep, warm hue. If one stuck one’s hand into the narrow slot created by the removal of a book, one found the same wood formed the backing of the shelves. Nor did the crow girl marvel at the ambient light within the library, accustomed as she was to a soft light filtered by nebulae that flooded through her own library.

When Hong Samud asked her to examine one of the doorways, seemingly at random, she stopped and inspected it. The same wood in which the rooms were lined wrapped around the edge of the stone entrance, extending in a casing about half a foot wide, in which the doorway was framed. To the right of entrance on rooms, which lay on the outside of the spiral, a small brass plaque provided a room number. Those rooms lying on the interior, had an analogous plaque, though placed on the left. If there was a significance behind this arrangement, Hong Samud did not share it with the crow girl. For her part, she got down on her hands and knees and crawled around, inspecting the threshold of the entrance, but found no visible change in the stone tiles.

“Do you think that you will be able to determine where each path leads simply by inspection?” he asked.