|

|

|

|

The Poison Pie Publishing House presents:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

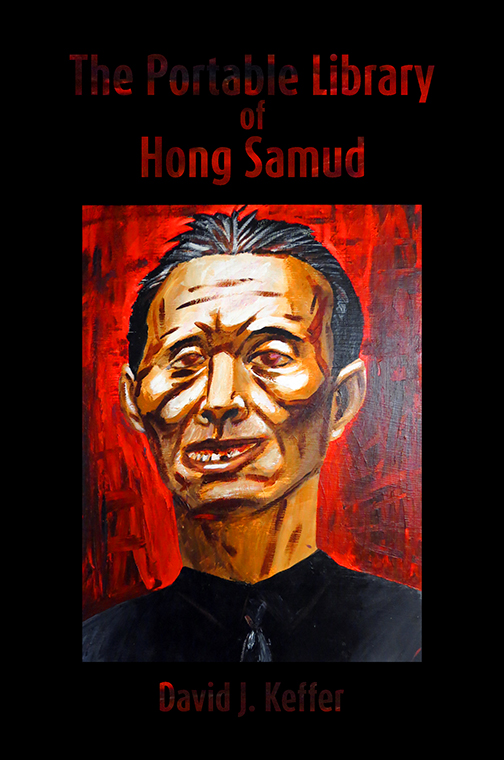

The Portable Library of Hong Samud

(link to main page of novel)

November

|

|

|

|

|

November 1, 2015

On a Dream of the Warlord

It was not unusual, after the warlord had had his way with a concubine in his bedchambers to have her remain with him for the duration of the night. Like many lovers, he found comfort in the natural rhythms of a warm, supple body beside him. And, in the morning, if he woke with a young beauty in his bed, his thoughts often returned to sex, which seemed a pleasant way to begin a day that would invariably be consumed with many, less satisfying issues of the bureaucracy of state.

Palace protocols had long been established for these semi-official trysts, one of which was that a soldier was stationed outside the front door to the bedchamber. The rear door, used by servants, was also manned for the duration of the night, by a stout, female member of the palace staff, thus ensuring the warlord’s privacy.

In the third watch of the night following the departure of foreign party, the warlord, always a light sleeper, awoke in darkness. As his eyes adjusted, the warlord examined the favored concubine, who lay sleeping deeply on her side with her back to him and her head upon a pillow, a sheet pulled up over her rib cage, exposing the side of a breast beneath her arm. Thinking to relieve himself, he climbed from bed and strode to a chamberpot beside a magnificent window. He pulled the heavy curtains aside and allowed the light of a full moon to flood the room.

Turning, he found to his astonishment a figure standing not fifteen feet from the foot of the bed, apparently having observed him in silence for some time. The shout he gave was muted only as it passed his lips, emerging with sufficient volume to wake the concubine but not to summon the guard outside the door. He recognized the white hair of his visitor in the moonlight.

The groggy concubine raised herself on an elbow and too perceived the stranger. In her experience, only two activities transpired in this room—sex and sleep. She therefore interpreted the presence of the legendary witch, someone she had prayed never to lay eyes on, as proof of the rumors that her lord fornicated with the emissary of devils and probably with a harem of lithesome succubi as well. Naked though she was, she leapt to her feet and fled from the room to through the servant’s door. She must have convincingly told the woman stationed there of the identity of the unexpected visitor, for no one ventured from that door.

“How did you enter?” asked the warlord, standing as a naked silhouette before the light of the window.

“It matters not,” said the diabolist, making clear to the warlord that she controlled the direction of conversation.

He obediently waited for her to speak.

“You have sent the foreigners to our home.”

“Only to be exterminated,” explained the warlord.

“You think to order my kind to do your killing work?”

“I rather thought,” said the warlord, feeling nervy, “that your kind might find something more interesting to do with them.” He imagined the depraved tortures of Hell.

“You understand nothing,” said the diabolist in an icy tone.

Again, the warlord found refuge in silence.

“You are to immediately assemble a force of men, adequate to this task. They will follow me upon the quickest path to the point where the foreigners will enter the underground. There your men will lie in ambush. When the party arrives, your men will slay all foreign members of this party. Then they will depart and return to you on their own. No one shall speak of this again.” She added with a particular emphasis, “They will spare the librarian.”

“It will be dark,” said the warlord in protest, “and in close combat. Who knows where the blows will fall?”

The diabolist was not pleased with this impertinent remark. She answered, “Make it clear to these men that, should the librarian be slain, they shall be fortunate to die, for not a one of them shall emerge to ever see the light of the sun.”

The warlord frowned in the moonlight.

“Go!” shouted the diabolist. “I am waiting.”

He swallowed his pride and dressed as the priestess watched him. He left her alone in the bedchamber, as he gave the orders for a score of men, skilled in both bow and blade to be made ready in black trappings, free of any armor or metal gear that would betray their movement.

Within an hour, this platoon of accomplished murderers, faced a sergeant unlike any they had yet served. The woman, young in the face, was white-haired and garbed in a robe that only partially hid her feminine figure.

“They are not to speak to me,” said the diabolist to the warlord.

“They would not so dare,” said the warlord. “I have already relayed your orders.”

Into the night, this party fled through the city. Beyond its borders, they found a hidden entrance to a cave. Abandoning moonlight, they traveled by paths no citizen dared travel without such a guide, who knew these labyrinthine passages by rote.

The warlord, for his part, returned to his bedchamber. He disrobed and noted the absence of his concubine. He thought of summoning her only to have her executed for having the ill fortune of observing the uninvited visitor to his chamber. However, he checked the impulse. She had possessed the wisdom to flee before she observed something that irrevocably sealed her fate. Her speculative gossip would only serve to breathe new life into the rumors of his dealings with the people of the devil. Perhaps, an account of his sexual conquest of the diabolist would portray him in a more favorable light, with respect to the distribution of power in their relationship, than was actually the case.

|

|

|

|

|

November 2, 2015

On the Mishap of the Apprentice Librarian

Guided by satellite positioning devices, the mercenary led his men, the prospector and the translator back to the cave entrance. They retraced their steps along the subterranean paths by the light of electric lanterns until they arrived again in the chamber at the end of which was located the passage, flanked by symbols of the pierced eye.

Whatever trepidation the apprentice librarian had felt upon descending into the earth was multiplied one hundred fold by the sight of these markers that matched the one on his thigh. No pretense could be maintained any longer; they had arrived at the border of the domain of the diabolist.

The party argued for a few minutes before the entrance. The mercenary felt it only natural that their native guide should lead them forward. The apprentice librarian countered, “It is better if we allow them to approach us on their own terms.”

“What?” barked the mercenary, “Just wait here for them to stumble upon us?”

“Oh,” replied the librarian, “I am fairly confident that they are already aware of our presence.”

This ominous warning put the party on edge but did little to prepare them for the ambush that was then sprung upon them. On a silent cue, twenty trained assassins rose from the perimeter of the cavern, completely cloaked in darkness. By the light of a dozen lanterns, they trained their bows on the torsos of those holding them. As one, the first volley was released. As screams echoed against the stone walls and the lanterns clattered against the floor, a second volley followed.

An arrow from the first volley pierced the apprentice librarian through the stomach. He too shrieked in surprise, terror and pain. He fell to his side and gazed in disbelief at the shaft extending from his abdomen, a ring of blood spreading from the wound. Gentle reader, we should do well to remember, that despite his unusual upbringing and the broad experiences he had encountered in his service to the diplomat, the apprentice librarian was still only a boy of fourteen. We can therefore excuse him when he cried out to the darkness, “Gyermek, it is I, your servant! Have mercy on me,” for he was rightly overcome with the fear of death.

Such was the rage of the warlord at having the sanctuary of his bedchambers violated by the diabolist that he had neglected to inform his assassins of her request to spare the librarian. That he might lose all these capable men as a consequence of this act of petty revenge seemed to the warlord an acceptable exchange.

The devil-worshippers who dwelt in a city far below these caves were indeed aware of the melee at their doorstep. Perched in shadowed niches positioned at high points around the chamber, their eyes were accustomed to darkness. They required no lanterns whatsoever. The diabolist had communicated to these sentinels the terms of her agreement with the warlord, which she fully intended to honor. When they observed the fall of the librarian, each sentinel released a bag of concentrated spores, collected from a fungus cultivated by herbalists among them. These spores permeated the air of their city; the residents had generations ago gained an immunity to their paralyzing effects.

The warlord’s agents had emerged from their own hiding places, bows replaced by swords, to deliver the coup de grâce to those foreigners who had not perished by arrow. As a silent, invisible rain of spores descended upon them, the assassins breathed in the paralytic agent. Only as their muscles stiffened did the realization dawn on them that their bodies had been compromised.

In half a minute, their spasms ceased and the warlord’s assassins lay statuesque, fallen in the pooling blood of those whom they had deemed their adversary. Now the sentinels descended from their perches and drew wicked daggers, in order that they might cut the throats not only of those foreigners who yet struggled but the warlord’s men as well.

Joining her people, the diabolist emerged from the dark passage between the markers. She wound through the corpses, the dying and the paralyzed. She watched her sentinels, men and women alike, engage methodically in their grisly work. She located the apprentice librarian and stood beside him, gazing down. He clutched at the shaft in his belly. His open eyes were full of terror. “My librarian yet lives,” the diabolist said in her native tongue. “I shall not let his supplication go unheeded.” Even as the killing continued, the diabolist ordered the medic among them to bind the boy’s wound and two strong men to carry him down to the city, where, if this was not the hour in which he was fated to die, he could be tended to. As he was lifted, the apprentice librarian grunted in agony and fell into unconsciousness.

He was therefore not aware of the surprised exclamation of the diabolist, as she meandered barefoot, looking for survivors in the corpses, thinking to partake herself in the ritualistic ending of life, and came upon the lone female of the party. “Ah,” she cried, “they brought a devil of their own with them!”

|

|

|

|

|

November 3, 2015

On the Second Reunion of the Librarian and his Apprentice

The time that the apprentice librarian spent in the infirmary of the underground city of the diabolist passed as if he were in a state of delirium. Since there are no other accounts of visits by outsiders to this city, we cannot determine whether this derangement was due to the natural concentration of spores in the city or, rather, was induced by pharmaceuticals, intended either to suppress the pain of his injury, alleviate the effect of other paralytic spores, or perhaps specifically to obscure his memory. Regardless, when the apprentice librarian had returned to the capital, he recalled his stay in city of the diabolist as if it were a dream, through blurred images and confused sensations. Someone had cared for him, nursed him back to health, of that there was incontrovertible evidence. He yet lived and the scar on his belly was not only that of a puncture wound but of an incision as well. He had been the subject of some unremembered surgery. Its only residual effect was a reduction in his appetite, which stayed with him for the remainder of his life.

When he had sufficiently recuperated, he remembered being escorted through the city, a collection of stone buildings arranged within an enormous cavern, illuminated by the bioluminescent fungi attached to the rough ceiling, decorated with stalactites, high above the pointed roofs. That light, in shades of pale green, blue and lavender, seemed to spread from its sources, obscuring the faces in his memory. However, perhaps because of his talent with languages, the voices he remembered quite distinctly. Although he had never studied the tongue of the diabolist, it too shared a common root with the many dialects he knew well. Eyes closed, he had lain in a cot and listened to conversations, some regarding his recovery and others regarding the daily, family lives of the nurses who tended to them. Again, it was hard to imagine that he had simply dreamed entire dialogues regarding the mundane conversations young women might have with each other as they passed hours, days and weeks beside an inactive, bedridden patient, yet such dialogues the librarian retained. Their recounting of squabbles with family and friends, their candid evaluations of potential prospects for marriage, their efforts to adjust work schedules to accommodate one social obligation or another, their review of novels of a romantic nature that they had both read—all such topics, real or imagined, were stored in his memory.

There were gaps in his memory, especially with regard to his departure from the city. He remembered being ushered through the streets beneath the eerie, fungal light to the city gates. He possessed no memory of wandering through the underground beyond the city. His recollection of his return picked up again only as he stood outside the passage flanked by glyphs of the pierced eye.

He judged that he had spent more than a month underground by the state of the corpses in the chamber. The decomposition of the bodies had proceeded to a point where the flesh had already begun to fluidize and seep from the bones, creating pools within the clothes, which served as homes for vibrant colonies of mold. In such a state, the apprentice librarian could identify the foreigners by their unusual clothes and a host of other men, once garbed in black. The origin and thus the allegiance of these men were beyond identification. He found it unusual that the residents of the city should allow such a putrid scene to develop at their doorstep. What he did not understand was that this passage was a remote and inconvenient entrance to city, rarely used. It had only been chosen for this grim encounter, due to its chance discovery by the foreign party. In future, these remains would prove at least as effective a deterrent to ward off trespassers as the glyphs above them.

The apprentice librarian hurried through this chamber. At the entrance to the surface, he found a mule prepared for him. Slung across the back of the beast were saddle bags. He opened them to find not provisions but the books on geology and mineralogy, which the foreigners had brought with them. He understood implicitly the destination for these parcels.

It took all of the day and into the night before he arrived at the library. Due to the late hour, his uncle was not there. The apprentice librarian found his key in the pocket of his trousers. He unloaded the books and dutifully returned the mule to the court stables, which he found unattended. Too exhausted by his journey to deal with his uncle, he returned to the library and slept on the floor.

On the following morning, he was discovered by his uncle, who said only, “They have returned you to me.” Such was the ambivalence that hovered over their reunion.

The librarian fed his nephew and demanded to see the wound, lest it fester due to inattention. They discovered the two scars, puncture and horizontal incision, both pink but well on their way to healing.

“What did they do to you?” asked the uncle.

“I do not know,” said the nephew. After a few moments, he added, “I suppose that they saved my life.” Neither spoke the question that was on both of their minds, ‘For what dire end had the diabolist spared him?’

When the nephew was tended to, the uncle examined the books, though he could not read them. One book had the head of an arrow and a broken shaft sticking from its front cover. The librarian wedged it free and examined it. “This is an arrow from the arsenal of the army of our lord,” he said to his nephew.

The nephew offered no explanation. It had been too dark during the ambush for him to see anything and his role in it had ended quickly.

The elder librarian pocketed the incriminating evidence. Later, he made sure that it was discretely tossed in the garbage of a market in a neighborhood he rarely visited, where it was unlikely to be discovered much less associated with the library.

At the end of his first day back, as they stood in the alley and locked the door behind them, intending to head home for dinner, the nephew said to his uncle, a veteran of many campaigns, “Well, Uncle, it has been made clear that I am no soldier. My first experience of combat went very poorly.”

The uncle shook his head. He had known many young men, ostensibly better prepared, who had met a worse fate in their first taste of battle. “Come,” he said, gesturing to the library door. “Let us hope it is your last.”

They walked side by side, down the empty alley. “Let us put this whole episode behind us,” said the uncle. “The foreigners are all dead. Let them not linger in our memory.”

Again, the nephew was presented with a dilemma regarding just what he should confide in his uncle. He opted for transparency, though in this instance it would not serve to reduce his burden. “Not all of them are dead,” he said.

The uncle raised an eyebrow then frowned.

“The woman was still alive. As I was leaving the city, I caught a glimpse of her, in a cage. They had done something to her face.”

|

|

|

|

|

Part Three. The Clerk & the Prospector

|

|

|

November 4, 2015

On the Clerk’s Termination

“Hong Samud! Uwe!” The insurance clerk’s cries echoed through the central corridor of the library.

“We are here,” called the distant voice of the crow girl, orienting the clerk to her position by the reverberations of her words along the spiraling hall.

The clerk ran clockwise, the two librarians counter-clockwise. They met both out of breath.

“Whatever is the matter?” huffed Hong Samud.

“She is lost!” gasped the clerk.

“Who? Who is lost?” asked the librarian.

It was not lack of breath but an unwillingness to add certainty to his fears by speaking them aloud that prompted the clerk to refrain from saying her name.

“Execrabilia,” said the crow girl, who, during her single lunch with them, had seen into the heart of the clerk.

“Who?” asked the librarian. Insulated in his library he had never encountered the name. If it had been mentioned in passing by the clerk, which he did not think to be the case, she had not registered in his memory—an unlikely event for such an unusual name.

“The prospector,” said the crow girl, “sent by the company to survey the mine.”

Catching his breath, the clerk nodded in agreement.

Observing the obvious distress of the clerk, Hong Samud asked, “Is she your wife?”

“No, she is not my wife. I am not married.”

“Do you wish to marry her?”

This unexpected question stumped the clerk, who had not come with any intention of revealing the contents of his heart to the diminutive and eccentric librarian. “I...” His voice trailed off. He tried again. “I...”

Even the obtuse librarian could perceive the trouble the clerk had in answering his question, so he thought to relieve him of his difficulty by asking a different question that might be easier to answer. “Does she wish to marry you?”

The clerk’s eyes widened in a combination of dismay and amazement. “She is lost!” he cried, implying that matters of a hypothetical union were utterly inappropriate in such a situation.

The crow girl intervened. “Tell us what has happened.”

They moved to a reading table in an adjacent room, where the insurance clerk related then that little information which was known to him. The party of contractors sent by the insurance company had failed to check in on time. This in itself was no surprise. Often in wild lands, satellite service was sporadic and rendered the regularity of the reports unreliable. However, two weeks had then passed without further word. So, the company sent a smaller expedition to locate them. As they all knew, having studied the situation better than anyone else, flights landed well outside the borders of this kingdom. To reach the capital required an additional ten days travel by caravan. Therefore, it was another two weeks before the second team arrived at the capital and were informed of the accident.

“Accident?” asked the librarian.

“That’s what they said. A minor quake resulted in the collapse of the entrance to the cave system that they were exploring.”

“Well?” prompted the librarian impatiently. “What was the fate of the party?”

It clearly pained the clerk to answer, but he did so knowing it necessary to achieve his plan. “We are told that no bodies have been recovered. They are buried too deep. There is little chance any could have survived for more than a month underground.”

The three sat in silence around the table. The face of the clerk expressed anxiety bordering on grief.

“Well, I find that explanation highly unlikely,” said the librarian abruptly, looking first at his daughter and then at the clerk. “We all studied the seismographic data rather thoroughly. There are no faults there.”

“That’s exactly what I said!” shouted the clerk in agreement. “But the company would not listen. They claimed that the data was obviously inadequate.”

The librarian took the questioning of the reliability of research that came from his library as a personal affront. He was about to embark on a lengthy expression of his indignation, but was preempted by his daughter, who had seen it coming.

“What are they going to do?” asked the crow girl of the clerk.

“Nothing!” he shouted in a fury. “They have decided ‘to call a temporary halt to the operation until such a time as better relations are established with the local government, which allow a more transparent understanding of the local situation’.” He quoted this last bit in a voice of disbelief.

“How quickly can that happen?” asked the crow girl.

“Years...Decades!”

Again the trio allowed a silence to fill the library. The crow girl allowed it to extend for several minutes, long enough she hoped for the clerk to regain some measure of calm. “What are you going to do?” she asked in a quiet voice.

“I’m going to go looking for her.”

“On your own?”

“If I have to.”

“Will the company lend its support?”

“Far from it,” said the clerk. “They have already forbid my going, on pain of termination.”

“And what did you say to that?”

“I don’t remember exactly,” admitted the clerk. “I was angry. But it must have been to the point, because they fired me on the spot.”

The librarian had listened carefully. He felt at this point that he understood the clerk’s situation well enough to ask a very pertinent question. “Why have come to us?”

From across the table, the clerk stared into the eyes of the librarian. “You have not told me the full truth of this library.” He stated the accusation as fact.

There was no such thing as a lie in the library of Hong Samud. “No, I have not.”

The clerk rose to his feet and declared in a demanding tone, “Tell me of the nature of this library that I might find in it the means to locate and, if she still lives, rescue Execrabilia.” He imagined that he cut a rather dramatic figure making such a statement. He was therefore disappointed by the underwhelming response of the librarian.

“Come back tomorrow. I need a night to sleep on it.”

The clerk looked to the crow girl, who pursed her lips; her father had already spoken.

Only after the insurance clerk had left the entrance of the Tower Library on Maple Avenue, did it occur to him that, according to Uwe, her father did not sleep. Consequently, that night the clerk’s dreams were filled with the imagined treachery of the librarian. In his dreams, he returned to the Tower Library only to discover that it had become a maze. He was forced to navigate it in order to reach the entrance to the Special Collections room that led to the library of Hong Samud. In the panic of dreams, he raced madly through a labyrinth formed by crooked aisles of books. When he finally reached the portal, he discovered to his horror, upon extracting his library card from his wallet, that the card was covered in a black tar. No matter how hard he scratched at it, he could not remove the sticky goo. No matter how vigorously he swiped the filthy card at the door meter, it would not grant him entrance.

At the back of his dream, watching the clerk from a spot just outside his vision lurked a crow. She thought it rather unkind that, though the clerk may have lacked trust in the librarian, he should have so quickly forgotten the presence of his daughter, who never, not in a million years, had abandoned someone in their hour of need.

|

|

|

|

|

November 5, 2015

On the Persuasion of the Librarian

As the librarian returned to those rooms containing the books dealing with topics related to the distant land in question, the crow girl followed him. “Agidoda, why did you not immediately agree to help him?” she asked.

The librarian did not answer at that moment. Instead, he pulled books of geology and seismology from the shelves and reassured himself that his earlier reading of them had been correct. Once this task was done, he thought to turn himself to texts of a cultural nature, but was forced to postpone that reading when the crow girl inserted a different book before him.

On the page that she had opened for him, he read of the mythology of the three dark gods and how the darkness itself had been distributed among them, paying special attention to the fact that subterranean darkness had been granted the domain of a devil god.

“What do you mean by showing me this?” he asked the crow girl.

“This is only the first half of what I mean to show you.”

She then led a reluctant Hong Samud from these rooms to those that had been created by the insurance clerk upon his entrance. He protested, saying, “I don’t know what good additional knowledge of the clerk will do us at this moment. Our time until he returns is limited...”

“Bear with me, Agidoda,” said the crow girl.

Together they read of the family legend detailing the origin of angelic blood in the Anxo family line. “This is,” said the librarian, choosing his words carefully, “a story not based in historical fact.”

“As am I,” agreed the crow girl. “And this library,” she added unnecessarily.

To this the librarian had no rebuttal.

The crow girl replaced this book on the shelf then withdrew a slim volume titled, “Erotic Daydreams of Insurance Clerks”.

“Good Heavens,” said the librarian. If he had noticed such a book before, he had pointedly avoided it. “Must we read that? In addition to the fact that reading such a book is likely an unwelcome invasion of our patron’s privacy, it also promises to be excruciatingly dull.”

“As dull as ‘Erotic Daydreams of a Lonely Librarian’?” asked the crow girl, mischievously.

“No such book exists!” said the librarian, though he cast a worried look at the shelves for fear that such a tome had gone unnoticed.

It turned out that that the book she held was an expurgated account, in which all passages deemed salacious were rendered in Latin, a language quite familiar to Hong Samud. Whether his daughter also understood Latin he did not ask. (He seemed to have forgotten, likely intentionally, that she had presented her ornithological library to him by its Latin name.) The crow girl’s suspicion that such a book might be useful turned out to be prescient. In truth, she had encountered the prospector once and did not have to build a case from scratch. What they found of interest in this tome was the infatuation of a man descended from angels with a woman descended from devils.

When they had closed this book, Hong Samud turned to his daughter and summarized their findings. “A woman come from devils entered a cave ruled by a devil. What do mean for me to infer from that?”

“You know from your studies of this culture that hostage-taking among warlords is a common political device.”

“I do,” admitted the librarian.

“The likelihood,” said the crow girl, “that the prospector was killed in a freak cave-in seems greatly reduced with this information in hand, does it not?”

Hong Samud did not immediately agree. Mentally calculating probabilities of such events as being swallowed by an earthquake and being captured by a devil were beyond his skills. “I suppose,” he granted the crow girl.

“She is not dead,” said his daughter. “That is not the way this story ends.”

“Perhaps.”

“Perhaps is enough,” said the crow girl. “We must help the clerk.”

Hong Samud was not convinced. “Think of the big picture,” he told the girl. “On the far side of the world, a woman working for an insurance company has been lost. A man who lacked the courage to express his love for her, in the face of this loss, now regrets his cowardice. If, as you suggest, this woman has been captured by devils, even if she is merely a hostage of a warlord in some scheme of local politics, it is beyond our capability as librarians to storm either the caverns or the palace and retrieve this woman. What heroic prowess do we have?”

Rather than declare at length the numerous elements of heroic prowess traditionally ascribed to librarians, the crow girl opted for an alternative argument. “You are looking at this the wrong way. This is not a case of a hostage rescuing operation requiring a team of highly-trained military commandos.”

From the expression on the face of Hong Samud, it was clear that he thought that the description just provided by his daughter accurately outlined the matter at hand. “Then what is the right point of view?” he asked in a challenging tone.

“This is a love story,” said the crow girl.

“In that case,” retorted the librarian, “I am even less fit to intervene.”

The crow girl ignored her father. She took the book from him, for he had not yet set it down and opened the book again, flipping to a page in which a picture from a block print was displayed. Although he feared it to be lurid, Hong Samud found only an image of a man, bathed in rays of light with a traditional depiction of angel wings, and a woman, with horns and the wings of dragon cloaked in a cloud of darkness, chastely holding hands, gazing into each other eyes in front of a fireplace. “Do you not see that they are fated to love each other?”

Hong Samud struggled to find some rationale by which he could counter the evidence that was presented explicitly before him.

“It cannot be denied,” said the crow girl.

“Perhaps,” Hong Samud half-heartedly agreed again, unconvinced.

“Perhaps, indeed, Agidoda” said the crow girl. “Perhaps, you are meant to help them find each other.”

Now the librarian truly looked taken aback. “Me? They don’t need my help; I can assure you.”

“Of course, they do. They need all the help in the world,” said the crow girl, waving off his objections. “Look at them—an angel and a devil. There could not be two more star-crossed lovers.”

“I cannot help them,” insisted the librarian. “I know nothing of romantic love.”

“Did you not set out to create a perfect world?” demanded the crow girl.

“Well, yes,” the librarian reluctantly agreed. “I did.”

“And in this perfect world is not the proportion of misery reduced?”

“One hopes so,” said the librarian, his resistance crumbling as he predicted the path of the crow girl’s argument.

“And does not love reduce misery?”

“So I am led to believe,” he admitted, “at least some of the time.”

“Then, Agidoda,” said his daughter, her gaze falling on the image of the clerk and the prospector kneeling before the fire, “you have your work cut out for you, for great obstacles lie in the way of this task and it shall not be easily achieved.”

|

|

|

|

|

November 6, 2015

On the Description of the First Library to the Clerk

The insurance clerk waited outside the entrance to the Tower Library on Maple Avenue for ten minutes before they unlocked the door for him.

“Busy day today?” asked the librarian.

“Indeed,” he replied as he hurried past her, intent on making his way to the special collections room on the second floor.

“Wait a moment,” called the librarian.

The clerk paused. “Yes?”

“Some months ago, you brought that black-haired girl here to apply for a library card.”

“I did,” the clerk admitted.

“She never picked up her permanent card.”

“As chance would have it,” said the clerk, “I am going to see her later today. I could deliver it to her.” He said this hoping to resolve the delay as quickly as possible.

“Would you?” said the librarian. She strolled to the front desk and flipped through a box of library cards waiting to be claimed. She plucked one from the box and handed it over. “We look forward to seeing her again. She was such a nice, quiet girl.”

The clerk thanked the librarian and hastened up the steps. When he entered the library of Hong Samud, he found the librarian and the crow girl waiting for him. She was surprised to be presented with the more durable version of her library card. In truth, she had not yet had the opportunity to use the temporary paper copy.

Let us not forget Hong Samud, who had been too afraid to return to the library to claim his own permanent card after his arrest for trespassing. He almost asked, “What about mine?” before he deemed it too petty a complaint to voice and simply allowed his eyes to covetously follow his daughter’s shiny plastic card as it disappeared into a pocket of her black dress.

“Well?” asked the clerk, disrupting the librarian’s train of thought.

The crow girl waited a moment for her father to speak but, when he hesitated, she feared that he might have unexpectedly changed his mind. Therefore, she spoke first, “We shall aid you in your search for Execrabilia to the best of our ability.”

“You will?” said the clerk with great relief.

“There was never any doubt,” the crow girl assured him, although the expression on Hong Samud’s face belied her words.

The clerk had already moved forward, his thoughts following a logical path that he had organized during those hours of the previous night when he had lain awake.

“First,” he said to Hong Samud, “you must explain the nature of this library to me. I understand it is not like other libraries, but it doesn’t fully make sense to me.”

Hong Samud considered for a moment whether the phrase ‘not like other libraries’ was to be considered a back-handed compliment. Regardless, he soon found himself, walking through the central corridor with his daughter and the insurance clerk in tow, as if leading a guided tour.

“It seems to be infinite,” said Hong Samud, “though not by my hand.”

The clerk had already moved past physics-based objections to the library. He focused his questions along other, more productive directions. “Are you a member of a fellowship of librarians?”

“Perhaps,” said Hong Samud, “although I don’t remember ever formally applying to such an organization and no member of any such group has ever presented themselves to me.”

“How can other librarians continue to add to this library and yet you never meet them?”

“It must have something to do with quantum mechanics,” Hong Samud speculated. He then described a wholly unsubstantiated theory that was founded on the idea that electrons and other particles subject to the laws of quantum mechanics were, strictly speaking, manifestations of a probability distribution, in which they were located across a range of coordinates in the space-time continuum but the variability was fixed when one interrogated their position, pinning them down if only for a moment to a particular location.

“In the same way,” said Hong Samud, “I am a manifestation of a continuous probability distribution of Hong Samuds. The others also work in their own domains. Based on the empirical fact that I spend all my time here and have never encountered another librarian, one can deduce that there is likely a law that prohibits more than one of us from simultaneously occupying the same point in the space-time continuum.”

In truth the rather outlandish philosophical perspective of the librarian served only to temporarily dampen the optimism of the insurance clerk, who wondered how such an impractical man would ever be able to help him find Execrabilia.

Over the course of the day, other secrets of the library were revealed to the clerk. That each door opened to another library somewhere in the multiverse seemed quite an excellent arrangement. The clerk immediately saw a potential utility. “I could leave directly from here to a library in the warlord’s capital.”

“Perhaps,” said Hong Samud, “but I foresee two difficulties with such a plan.”

“Yes?” asked the clerk, hoping, it turned out futilely, that the librarian’s objections were not insurmountable obstacles.

“First,” said Hong Samud, “the people of that region are notorious book burners.” He said the last two words as if there could be no lower entry in the annals of crime. “It is doubtful there is a library in the capital.” Certainly, he felt that a populace with such deplorable habits did not deserve a library.

Although the library of Hong Samud was extensive, it did not possess all knowledge. His portion of the library contained no mention of the relatively unpublicized existence of a warehouse in the capital where books were stored but not lent to ordinary citizens. Moreover, Hong Samud did not yet understand that information not in his portion of the library might be available in sections assembled by his unseen colleagues, who existed in parallel universes where the warlord’s library may have not been such a well-kept secret, or might even have been described in religious texts as a sacred temple at the altar of knowledge.

“Second,” said Hong Samud sheepishly, “I only know where three of the doors go.” He then was forced to explain to an incredulous clerk that he had no alternative but to rely on trial and error if he was to discover the destination of a door. The door to the clerk’s home he knew of only because the clerk himself had come through it. He had encountered the crow girl only by chance.

This admission confirmed the clerk’s long-standing suspicion that the father-daughter relationship between the librarian and the crow girl was not of a traditional, biological sort. “And the third door?” asked the clerk.

“The third door,” said Hong Samud, “convinced me of the danger in wandering through doors to unknown destinations.”

“Where did it lead?”

“I would rather not say,” said Hong Samud. “It is of no relevance to the matter at hand.”

“How can you not know where the doors from your own library go?” protested the clerk. “You built this library!”

Hong Samud shrugged. He offered only another hypothesis. “I created this library to be a perfect world. I can only optimistically suppose that an associated uncertainty is an aspect of perfection.”

Although the clerk was not satisfied by this answer, he had no other recourse but to accept it.

The crow girl next described to the clerk the efforts of their research during the previous night, which led them to believe that the chances were better than they had originally estimated that the prospector was still alive, though perhaps not at liberty to contact them. In this description, an additional property of the Hong Samud’s library was revealed, namely that each visitor to the library inadvertently created additional rooms filled with books, real and imagined, related, even peripherally to the story unfolding during his or her life.

Upon hearing of this trait of the library, the clerk nursed a feeling that he had been taken advantage of, a reaction to which the crow girl could sympathize since she had felt the same indignation. The clerk insisted upon seeing the rooms that he had created.

Their path led them past the crow girl’s rooms, in which the books all took the form of birds.

“Your rooms are marvelous,” exclaimed the clerk in amazement.

The crow girl blushed with pleasure at the praise.

However, the clerk was disappointed when he discovered that his own room was filled with ordinary books composed of paper and ink. As he perused a random selection of books, he did not notice that Hong Samud remained standing in a single spot, discretely blocking access to those books behind him, which included, among others, “Erotic Daydreams of Insurance Clerks”. He hoped only to spare them both some embarrassment, for there was no such thing as a lie in the library of Hong Samud and if the clerk were to discover the book and ask the librarian if he had read it, he would be forced to answer truthfully.

When the clerk had satisfied his curiosity, the trio turned to business. The plan they agreed upon was simple. The two librarians would provide what useful knowledge they could up front. The clerk would travel alone by conventional means to the capital. There he would locate a local library, either in the warlord’s realm or as close to it as possible, where he would establish a point through which he could communicate with the librarians as the need arose.

It seemed a rather a sparse and mundane plan, which exposed only the clerk to danger. All of them, Hong Samud in particular, felt the inadequacy of it, but he reassured himself that it was a sufficiently flexible course of action. The plan could be modified. They could improvise, a talent admittedly in short supply in Hong Samud, but presumably his dearth was more than compensated for by the cornucopia of serendipitous unpredictability who had come to identify herself as his daughter.

|

|

|

|

|

November 9, 2015

On the Departure of the Clerk

It could not have been more apparent to the insurance clerk that he was woefully unsuited to the task at hand. His aversion for the rigors of travel and the associated deprivation of familiar comforts grossly outweighed any sense of adventure or curiosity about new cultures that may have resided within him. Nevertheless, he embarked on a journey to the other side of the world in order to determine the fate of the woman he had come to love. The undeniable fact that he had not yet managed the courage to declare his intentions to her was pushed aside. His actions in this regard would speak louder and more earnestly than any words he might have uttered.

Still, a great trepidation as well as a lingering sensation that he was engaged in the commission of an egregious error accompanied the clerk as he filed in a line of passengers through the rain on the tarmac onto the aircraft. If anything, his foreboding had intensified when, nineteen hours and one layover later, he filed off a much smaller aircraft into the dry heat of this intermediate stop in his journey.

This city was the secondary, inland capital of a neighboring nation contiguous along this interior border with the wild lands ostensibly governed by a multitude of warlords. Because this neighboring country possessed a coast, it had centuries ago come into contact with numerous distant, foreign nations and established mercantile relationships with them through their ports, which led subsequently to the exchange of ambassadors and other diplomatic courtesies.

However, the international, cosmopolitan air of the primary capital on the coast did not translate across the intervening mountain range and into the desert plateau of the interior. Not only was the spoken language different, but the minority population of the interior felt poorly represented by the elected government of the coast and thus demonstrated questionable allegiance to the national cause.

Still, interest in the interior proved sufficient to establish a rudimentary airstrip. From this strip, the insurance clerk approached the humble terminal, a squat building, painted first in white latex, then shadowed with an accumulation of ochre dust in every ridge and corner. Where metal was exposed, enough moisture appeared seasonally to give rise to rust, which outlined each window. The dried tracks of rust-colored water, streaking the sides of the building, persisted in the dry season. This image greeted the clerk as if to say, “Here, though this people do not trust you sufficiently to reveal its existence, there is a sorrow common to all men; traces of its passage abound if one remains attentive.”

The pamphlet of practical phrases that the crow girl prepared for him proved sufficient to allow him to communicate to the bicycle-powered rickshaw of his reservation at a hotel for foreigners. Even more useful was the pouch full of bird-faced coins the girl had given him, for the driver of the rickshaw refused to accept his foreign currency but enthusiastically received a coin once proffered. He speedily brought the clerk from the airstrip into the city center.

If the clerk had felt far from home upon disembarking from the aircraft, once he was submerged in the aromas and myriad sounds of an utterly foreign culture, he felt the weight of his separation from all things familiar. Everyone, adults and children alike, pointed at the foreigner with blond hair and pale complexion, garbed in a finely tailored suit and clutching at his hat and walking stick lest he lose them on the bumpy ride. The clerk did his best to maintain his dignity but the absurdity of his position did not escape him, beginning, of course, with the fact that, as noted above, he was completely unprepared for the task at hand. Once he adjusted his perspective to admit the presence of an absurdity beyond his control, his role as a ridiculous spectacle seemed not altogether inappropriate.

The two story hotel appeared to have been built a century earlier to accommodate a more rarefied clientele. The clerk appreciated the odd juxtaposition of an aged grandeur of the imported architecture with woven rugs bearing intricate native designs in dyes of maroon, slate and navy. Although his room had been advertised as offering both electricity and hot water, it provided only the latter. The manager, who spoke considerably more of the clerk’s language than did his guest of the native tongue, blamed the lack of power on inevitable though sporadic brown-outs. The clerk cared little, intending to stay in this city no longer than it took to arrange passage on a caravan to the warlord’s capital.

The agenda of the clerk included no sight-seeing of statues carved in nearby bluffs of giants with historical and religious significance. Nor did he partake of a once-in-a-lifetime (so he hoped) opportunity to experience a cuisine that had not managed to be exported beyond these borders. He kept to an ascetic’s diet of water, bread, fruit and a kind of tuber, previously unfamiliar to him but nonetheless filling and bland only because he requested to the best of his ability that no spices be added during its preparation.

The clerk had only two destinations in this city. First, he had the manager draw him a map to the library. It took some time to communicate the idea for library was not a word the manager knew. After considerable confusion, the building, modest and dusty, (in other words inconspicuous from those around it), which the clerk arrived at turned out to be a kind of storehouse of local records: births, deaths, marriages, property transactions and the like. The official seated at a desk just inside the door could not communicate with the insurance clerk. However, apparently the clerk was not the first foreigner to visit; the official took him to the same corner where the other foreigners, better able to communicate, had requested to be brought.

There the clerk found a room, the size of a small office, filled with a haphazard assortment of books, some foreign and a few local. “Ah, the special collections,” said the clerk, recognizing it immediately and bowing in appreciation to the official.

Left alone, the clerk examined the doorway. He felt sure that this was the spot to swipe his card and gain access to the library of Hong Samud. Many of us in a similar situation might have immediately done so, in order to reassure ourselves that such a physics-defying action was available to us as well as to find a familiar face, having just arrived in a strange land. Perversely, the clerk, though tempted, did not visit Hong Samud. The knowledge that such a pathway existed proved sufficient. He also accepted that this library was yet ten days from the warlord’s capital. It would behoove him to find a more convenient point of access.

The books themselves possessed no interest to the clerk; who paged through a couple only briefly. Upon his departure from the library, he expressed his gratitude to the official with a single bird-faced coin. The official smiled and certainly accepted it, though he smoothly dropped it in his pocket as if it had been a bribe, not to be publicly acknowledged.

The clerk returned to the hotel in higher spirits. Not only had he accomplished the first of two tasks on his agenda but he had refrained from giving in to a need for reassurance. It seemed a kind of courage, or at least an acceptable substitute.

When the hotel manager saw him he explained, in stumbling phrases, that he had successfully managed to book the clerk passage with a caravan going to the warlord’s capital. The fare was the cost of the mule that would carry him, which would be forfeited to the caravan upon arrival, plus a negotiating fee for the manager, who repeatedly assured him that he was getting a “swanky deal”. The clerk settled the account with foreign bills. Several times during the counting of the money, the manager told him that he was the only person in town willing to accept such currency, since it required a trip to the port capital to exchange it. An only partially comprehensible story about his son-in-law’s trading excursion in the port then followed.

The clerk stayed the night in the hotel. On the following morning, as he was about to depart in the company of a courier who had been instructed to deliver him by rickshaw to the waiting caravan, a second, younger courier rushed into the hotel lobby.

Identifying the visitor by sight, the boy shoved a parcel into the clerk’s hands. Through the manager, he explained that word had gotten out that a foreigner was traveling to the warlord’s capital. Some years ago, another foreigner, before departing, had left a package to be delivered there.

“To whom am I to deliver this?” asked the clerk, confused.

The manager again translated. “The tongue,” he said.

“The tongue?”

The courier stuck out his tongue and pointed to it. He said the word in his own language and nodded.

“The tongue,” confirmed the manager.

The courier next grabbed the traveling bag of the clerk and impatiently urged him to get aboard the rickshaw. In the rush, the clerk did not have the opportunity to ask why the package had remained undelivered for years or who had held it for such a time. If he had done so, he would have discovered that no locals dared to transport it, for they feared the justice of the warlord should they be caught with it on their person. Of course, this explanation would have been sufficient to reveal to anyone with any familiarity with the warlord that the parcel contained a book. The clerk remained utterly uninformed. He did not even understand the manager’s parting admonition, “Veil it! Veil it!” by which he had meant to instruct the clerk to, by all means, keep the parcel hidden.

|

|

|

|

|

November 10, 2015

On a Daydream of the Clerk

The mule was laden with supplies—food and water for the trek—and the clerk’s bag. He walked beside it, as a pair of ill-matched but stoic comrades in misfortune. The merchants and guards comprising the human component of the caravan ignored the clerk. They spoke among themselves not in the language of the city they had just left but in a dialect found within a region of the warlord’s realm. The crow girl had provided the clerk notes on only two languages, those used near the airstrip and in the warlord’s capital. Consequently, the clerk better understood the brays of the mule than he did the words of his bipedal companions.

At the beginning of the journey, he thought of ten days spent walking along a dusty road, flanked by expanses of barren steppe, as a virtual infinity. He found this premonition not far from the truth for the isolation combined with the regular patterns of his steps and his breathing soon induced in him a trancelike state where the movement of time did not dominate his thoughts. Instead, the insurance clerk found himself wandering through daydreams.

He imagined, too many times to be counted, the surprise of the prospector, when he appeared to her. He found her in good health and humor. In his imagination, her failure to communicate for the past several weeks was the result of nothing more than a misunderstanding; she and her companions had simply forgotten that they were supposed to report periodically. Therefore, she asked him, “Why have you left your office?”

Embarrassed, he expressed his concern for her safety. Her companions conveniently disappeared into the surrounding mist of the dream.

She upbraided him, though tenderly, for worrying unnecessarily.

It seemed, in the dream, a moment had arrived for the unequivocal declaration of his love. He reached for her hand and she allowed him to take it. “Execrabilia,” he began, but he lost his courage and could not finish the statement.

Her brown eyes glanced expectantly from his face to her hand held in his, waiting.

The clerk felt an awkwardness approaching. His mind raced for something to say to fill the silence. He remembered a story. “Execrabilia,” he began again, “have you ever heard the story of the augur in the arbor inn?” She hid her disappointment and admitted that she had not. The clerk then explained to her that an augur had predicted that there was dire need for the most miraculous tree ever to be grown in this world or any other, though he did not specify the nature of the need. This tree could only be constructed by the careful splicing of genetic material from eight trees, some found only in exotic locations. After consulting his grandfather, the augur hired a monk and her apprentice to gather seeds from these eight trees from which the miracle tree could be constructed. The monk and her apprentice embarked on a grand journey across the realms of existence, eventually succeeding in collecting these seeds—rosewood from a realm of mirrors, lignum vitae from an aberrant realm, oak from Faerie, redwood from a realm of ghosts, ebony from a fortress of undeath, teak from Heaven, elder from Hell and willow from a realm of swamps. From this collection of specimens, the augur’s father, learned in such ways, constructed an unnatural, arboreal progeny in defiance of the laws of evolution. “It is said that the resulting tree is capable of granting any miracle.”

The clerk had looked away while recounting this story. He returned his attention to the prospector, who had listened patiently, curious to see where this odd digression led them. “Execrabilia,” said the clerk, “I ask you to accompany me on a journey to the tree of miracles.”

“It sounds interesting,” she agreed tentatively. “What miracle will we find beneath the boughs of this tree?”

“Ah,” said the clerk, “courage.”

One can therefore accept without much difficulty that when the ten-day journey had elapsed and the caravan arrived at the warlord’s capital, the clerk, who had passed the time in such an amiable way, felt as if no time had passed at all.

|

|

|

|

|

November 11, 2015

On the Clerk’s Audience with the Warlord

The word spread quickly that a lone foreigner had arrived in the capital. His bag was unloaded from the mule and he was abandoned by the caravan at the side of the stables. Given his virtually non-existent command of the language, the insurance clerk had not yet managed to secure lodgings when he was accosted by a low-ranking functionary of the court and a pair of guards. Despite the language barrier, the functionary managed to convince the clerk to accompany him to the palace; the presence of the guards provided appropriate emphasis.

Although we have already observed many exchanges within the palace, we have not yet described the edifice. In fact, the term palace is applied more in the functional sense that it served both as the abode of the warlord as well as a location for matters of state to be settled. In form, it more resembled a fortress or compound, for a wall of stone and mortar surrounded not only the principal edifice but a host of surrounding, ancillary structures as well as the square in which the warlord had first laid eyes on his howitzer. As the clerk approached the wall, he noted both its solidity as well as its lack of adornment of any kind. This was the wall of a ruler who easily dispensed with pleasantries.

The clerk was led to the side of the paved square, then through a virtual maze of passageways and alleys until he reached what he fortunately failed to recognize as an interrogation chamber. There he waited with a mixture of trepidation and patience, while the court functionary left guards outside the door as he went to consult with superiors.

A higher ranking official disturbed the warlord during a military briefing with news of the foreigner’s arrival. The warlord was of two minds. Standard procedure dictated that the translator should be sent to ascertain the purpose of the unwelcome visitor. However, since that translator was none other than the apprentice librarian, who had managed, apparently under the protection of devils, to return to the capital from the ill-fated venture in which a score of the warlord’s assassins had disappeared along with the first group of foreigners, he did not want to allow a private meeting between the two. Both were summoned to court.

The apprentice librarian was positioned to the side of the warlord’s chair prior to the arrival of the foreigner. Various officials assumed their positions along the perimeter of the room. As for the clerk, he stepped into the chamber, understandably nervous.

In an instant, the warlord accurately assessed the clerk, deeming him a weakling who posed no threat whatsoever. He immediately thought to adjourn the interview but, having allowed matters to proceed this far, he chose to devote a few minutes of his time to the clerk.

Through the apprentice librarian, the warlord asked, “Why have you come to my capital?”

“I am searching for a party of my compatriots,” replied the clerk.

“As I told the last group, they were all lost in a tragic accident. Did you not receive this message?”

“I did.”

“Then why have you come?”

“I wish to confirm this report.”

“It is confirmed,” said the warlord with finality. He rose to his feet, as if to leave. An official hurried forward to escort the clerk from the room.

“My lord,” called the clerk via the translator. “I have come so far and I do not wish for my efforts to have been made in vain. May I make use of your library?”

As the word library, the warlord sat back down. He looked sidewise at the translator, thinking there should be no reason for the foreigner to know of the dual role of the translator as apprentice librarian.

The apprentice librarian for his part made the utmost effort to keep his face and voice free of any expression.

“The favor you ask is great. Access to the library is not easily granted,” stated the warlord. “What do you seek from my library? And what do you offer in exchange?”

The clerk squirmed uncomfortably under the brutal gaze of the warlord, but the official was at his elbow, posed to remove him from the chamber at the slightest gesture from his lord. The clerk could not delay. He knew no more powerful weapon than the truth. He thus wielded it, despite Hong Samud’s advice to contrary. “I seek to find this party or what remains of them. One of them is dear to me.”

The warlord was traditionally unmoved by arguments relying on compassion and this instance proved no exception to the rule.

Observing the warlord’s response, the clerk added, “Your library may hold information that can help me find them.”

The warlord looked warily at his translator; he feared the extent of the truth of the foreigner’s words. He regretted allowing this audience; this was all a needless irritant. Nevertheless, the warlord asked again, “What do you offer in exchange?”

The clerk replied, “I offer nothing less than the surety that, having aided me, you will have contributed to the reduction of misery on this planet.”

The apprentice librarian frowned but dutifully translated these words.

The words elicited not so much as a smirk from the warlord, who rose, irritated that the foreigner had wasted his time, and dismissed the clerk with a glance at the official.

“My lord,” called out the clerk in a louder voice as the official took hold of his arm and the guards moved forward to drag him forcibly, if necessary, from the chamber.

The clerk then resorted to the tactic with which Hong Samud had argued he should have begun. “I offer this,” he shouted. “I will free you from the yoke of the devil that hangs around your neck!”

The apprentice librarian dared not translate this declaration in the presence of ordinary guards and officials.

The warlord looked to his translator for a rendering of this outburst and was annoyed further to find the boy shaking his head from side to side. In barking commands, the warlord ordered everyone out of the chamber save for the foreigner and the translator.

When the room was emptied of all but the three of them, the apprentice librarian said to the warlord, “In return to access to your library, this foreigner offers to free you from the thrall of the devil under which you labor.” The translator was unwilling to risk enraging the warlord by invoking the image of him as a beast of burden.

“How?” demanded the warlord.

“I have associates,” said the clerk, more nervous than pleased that he had finally gotten the full attention of the warlord, “who have experience in transactions with devils.” Calling Hong Samud’s frantic escape from the devilish librarian in the University of Hell, Phlegethon Campus, a transaction was a stretch, but the clerk, who had not witnessed the exchange, imagined it in more dignified terms, which added a strength, albeit undeserved, to his words.

“Where are these companions?”

“They are waiting for me.”

“I was informed that you came alone.”

“My associates do not travel by conventional means.”

At these words, the warlord imagined a djinni or some similar spirit carried on a vortex of wind and sand. “Fantasy,” he scoffed.

“But, if true, the potential reward is great.”

“As is the punishment, when you fail to deliver on your desperate, impossible promise,” snapped the warlord.

“Then ask no more questions,” said the clerk, “and, by your ignorance, you will be protected from any repercussions of my failure.”

The warlord contemplated having the clerk immediately slain in this very chamber for such a show of disrespect. But his resentment of the power that the diabolist wielded over him was the single greatest source of uncertainty in his reign. The diabolist represented the only threat to a flawless hegemony. Ever the doubt that he worked at the whim of a fickle god gnawed at him and robbed him of the peace-of-mind that he would otherwise have known in great reserve. The warlord had never been presented with so much as the intimation of a plan to remove this doubt. That the foreigner knew of his weakness spoke of a hidden source of knowledge. All that the man asked for was access to the library. The diabolist had never explicitly forbidden the warlord to open the library to the public. He wrestled with these thoughts—the ambition for an unconstrained power and the fear of an otherworldly retribution.

“Take him,” he barked at the apprentice librarian, who grabbed the clerk by the arm and hurriedly rushed him out of the chamber before the warlord thought better of his rash words and ordered them both thrown in the gaol, or worse.

|

|

|

|

|

November 12, 2015

On Connecting Libraries

“Who are you?” the warlord’s librarian asked the stranger, as they sat across from each other at the table by the second floor window of the new library.

As the apprentice at the side of the table translated, the clerk surveyed the one-legged librarian, who seemed to have almost nothing in common with the typical notion of a librarian. There was an underlying hardness to this man, a residual, military bearing. In sharp contrast to Hong Samud, it was difficult for the clerk to imagine the man before him possessing any affinity for archaic knowledge. Again, the clerk relied on the truth to carry him. “My name is Anxo. I am...was...a clerk for the Sigil Insurance Company, which sponsored the trip of the surveyors that disappeared more than two months ago. I have come to investigate their disappearance.”

This information did not satisfy the librarian. He looked sideways at his nephew. The nephew recounted in full the exchange before the warlord, including the singular promise that had caught the warlord’s attention.

The librarian listened in silence to these words. Halfway through the events, he closed his eyes. When his nephew had finished speaking, he opened them and addressed himself to the clerk. “The warlord has granted you access to his library. Find what you need, then go. Your presence here can only bring harm to us.” The nephew translated.

The clerk thought this a rather inhospitable attitude for a librarian. As he understood it, patrons were rare in this library and understandably so, given the rough treatment they received. He could not help but contrast this behavior with the welcoming attitude of Hong Samud when the clerk had arrived as his first patron.

“What information do you require?” asked the librarian, almost as if it were a demand. He specifically did not ask for any further knowledge regarding the plan to free the warlord from his service to the diabolist. He wanted absolutely no part in what he considered to be a pending disaster; he hoped only that he and his nephew would be able to escape the resulting collateral damage, though he thought the prospects of such an outcome poor at best.

“I need to find out where the surveyors disappeared.”

“I can assure you that such information is not written in any book to be found in this library,” said the uncle through his nephew.

“There may be some clue in one of your books as to where they would have likely gone. If not in your books then perhaps you can lead me to a laborer who accompanied them?”

“None would willingly go with them,” said the uncle, shaking his head.

“Why not?” asked the clerk.

“Because your friends foolishly wandered into a wasteland from which no one returns.” The uncle pointedly did not look at his nephew as the young man translated these words. “If you think to follow them, your fate will be no different.”

The clerk nodded. “I am compelled to follow them, even if it is a certainty that I too shall disappear.”

His resolve in speaking these words struck the librarian, who clearly had misjudged the clerk, with his prim manners, ridiculous top hat and the affectation of his walking cane, as a fop.

The apprentice librarian, of course, knew very well where the bodies of all of the foreigners but the prospector lay, for he had accompanied them there, though, as his uncle noted, not willingly but under the command of his lord. It was not his place to contradict his uncle in the presence of the clerk; he held his tongue.

The librarian and his apprentice were not prepared for the clerk’s next words, which took the form of a request. It communicated to them only the premonition that they did not understand the resources of this peculiar foreigner, for he said to them, “I should like to visit the special collections room, if you please.”

Since the only room that could vaguely be construed as a special collection in this library was the small room in the back of the old library where the unholy texts were kept, the librarian immediately assumed that, somehow, the clerk knew about these books, knew that the tomes held the secrets of dark gods, knew that his comrades had disappeared at the hands of a devil. Both the librarian and his apprentice wondered just how much the foreigner knew.

Regardless of their doubts, the librarian led them down the steps and over to the old library. Because it had no windows, it was dark inside even at midday. The apprentice lit the oil lamp as soon as they entered, then closed and locked the door behind them. The trio walked single file through the aisles until they arrived outside the doorway to the room. The apprentice stepped to one side and the librarian shifted on his crutches to the other. The clerk walked between them and surveyed the doorway in the flickering light of the lantern. For more than a minute he appeared to examine the room until he was satisfied that, indeed, this was the room that would suit his needs.

The warlord’s librarian and his apprentice watched the clerk remove a small, flat, rectangular object from his pocket. No details were apparent in the poor light. They observed him slowly pass the card over the border of the doorway on the right hand side. The shape of the shadows beyond the doorway seemed to flicker, but not in any way that could not have reasonably been attributed to an eddy of air moving past the lantern and disturbing the flame.

The clerk turned to the librarians. “I shall be but a moment.” He then stepped through the doorway, disappearing into the shadows of the room beyond.

The librarian and his apprentice wondered what the stranger could be doing in the darkness of the room, where there was certainly insufficient light by which to read. After a minute or so, the nephew stepped forward with the lantern. “Anxo?” he called out to the darkness. Receiving no reply, he too stepped through the doorway. To his surprise, he found the small room empty of all but its books.

|

|

|

|

|

November 13, 2015

On Establishing a New Entrance to the Library

“Six hundred and fifty-two,” shouted the clerk. His voice echoed through the central corridor. “It’s doorway number six hundred and fifty-two!”

Summoned in this way, Hong Samud and the crow girl arrived in due time. Hong Samud looked curiously from the way from which the insurance clerk had emerged and the doorway immediately across the hall, labeled 651, which, for those readers without a memory for numbers, was one of the three portals with a destination known to Hong Samud.

Rather than discuss implications of the proximity of these two doors, the trio settled down at the table in room 652. “I cannot stay long,” said the clerk. “The librarian and his apprentice are waiting for me.”

“Who?” asked Hong Samud.

The clerk quickly provided a description of the warlord’s library and its caretakers. He apologized for the brevity and his ignorance of many details, saying, “I only arrived in the capital this morning.” Of the various deprivations he had suffered during his journey to the capital, he (heroically, or so he thought) said nothing.

When the bulk of the story had rushed forth from the clerk, Hong Samud asked, “Did anyone see you enter my library?”

The clerk immediately sensed his concern. “It was dark,” he said. “The librarian and his apprentice must have seen only shadows.”

The crow girl too understood the librarian’s concern. The clerk had been the only patron to know how to enter the library and seemingly had accessed it initially on accident. Now two more had borne witness to the secret. From one to three to a multitude of patrons, the crow girl could clearly read in the librarian’s expression, his fears of an exponential growth leading to the library being flooded with patrons. “Calm yourself, Agidoda,” she said. “The library must be opened if your dream is to come to pass.”

To his credit, Hong Samud did not protest nor share in words his misgivings. Instead he prodded the clerk for additional details.

“I tried to tell the warlord the truth,” said the clerk.

“Did it work?” asked the crow girl.

The insurance clerk glanced at Hong Samud. “No. As your father predicted, I had to rely on his fear of devils to enlist his aid.”

The crow girl then asked, “Did the warlord believe you could help him.”

“Ha!” laughed the clerk. “He was no less skeptical than I myself am!”

“Yet he let you go,” said the librarian in a contemplative voice.

“A chance decision that fell our way, nothing more,” said the clerk.

“Fortune favors us,” said the crow girl optimistically.

“What will you do now?” asked Hong Samud.

“I will try to retrace the steps of Execrabilia.”

Fifteen minutes had already passed. “I must return to the library. They are waiting for me,” said the clerk. “If the librarians leave, I shall be locked in darkness, for their library is peculiar and has no windows.” The way the clerk said it made it sound like a dungeon.

Hong Samud took offense because, truthfully, his library also lacked windows.

The crow girl avoided an argument simply by patting the librarian on the back, “There, there, Agidoda. You have no need of windows when the light of knowledge emanates from the very fabric of the library itself.”

Appeased, Hong Samud led the others out of the room. They watched the clerk activate the portal. Through the doorway, they saw a lantern and two human forms waiting for him, though they could not make out, in the darkness, the details of the faces. The portal closed.

Hong Samud looked at his daughter. “If it comes to a confrontation with a devil, I fear our helplessness will be exposed.”

“Agidoda,” said the crow girl, “how can you say such things in your own library? Did you not make it to be perfect?”

The librarian nodded. He fell to imagining an aspect of perfection, improbable as it may seem, in which the library mysteriously provided a means by which the laws of nature could be upended and the lamb could conquer the lion, or at least dine at the same table without threat of becoming part of the feast.

|

|

|

|

|

November 16, 2015

On a Concise Description of the Library

The warlord’s librarian and his apprentice had waited in the light of the lantern outside the doorway to the small room where they kept their theological texts until the foreigner re-emerged. The doorway again flickered. This time however, within the shadows that materialized were the static forms of two other individuals, flanking the clerk as he stepped through. Although the details were partially obscured by the darkness, it seemed that one of the figures was a diminutive man and the other a girl, roughly the same height as the man, though much paler in face.

The portal closed leaving the three men standing in the old library. “You have questions,” said the clerk. The apprentice translated these words for his uncle, who nodded.

“They should be answered in the light.”

The three men returned to the table by the window on the second floor of the new library. There the insurance clerk began his explanation with the following words. “It may come as a surprise to you (it certainly was to me) that all libraries in this world and in worlds beyond are connected by another library, which exists outside all worlds and contains well-catalogued knowledge, both infinite and yet incomplete. It is to this library that I traveled to consult with the librarians who dwell therein.”

This explanation proved exceedingly easy for the warlord’s librarian and his apprentice to accept for they did not have extensive experience with libraries, knowing only this single institution under their own care, and they already regarded it already as an edifice inextricably linked to the supernatural. Perhaps, more surprised than the librarians at his declaration was the insurance clerk at their lack of response to it.

“In that case,” said the clerk, as the apprentice translated, “I shall continue. I have established a connection between your library and this other library. If need be, the librarian—his name is Hong Samud—may choose to visit your library through this portal. But as the circumstances stand, he would be locked inside that building in the dark...”

“Who is this librarian?” interrupted the warlord’s librarian.

“Is Hong Samud a devil?” translated his nephew.

“No, no,” said the clerk, who then paused before adding, “At least I don’t think so.” He looked at the nephew to reassure him. “There is a gentleness to him that is not commensurate with the typical notion of devilry.”

“What does he want with our library?” asked the uncle.

“Oh, I am sure that he would find your library fascinating,” said the clerk, intending it as a compliment. “He seems to have an indiscriminate taste for books. Still, he would not venture forth simply to peruse the contents of your library.” He looked at the expectant faces; they wanted him to cut to the chase. By way of direct explanation, the clerk offered, “Hong Samud has some experience dealing with devils. It may yet come in handy.”

“He will keep your promise to the warlord?” asked the nephew.

“If not him,” agreed the clerk, “then, I think, no one will, certainly not I. I am wholly ignorant in such matters.” He added this last sentence in a stuffy tone, as if it were a point of pride.