|

|

|

|

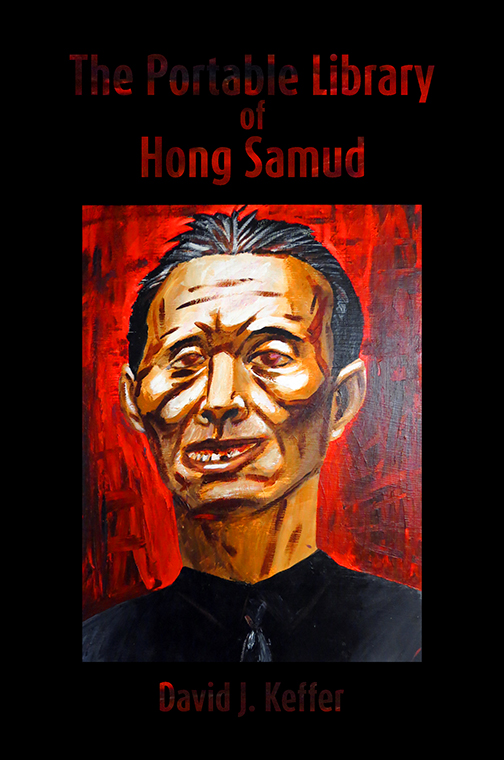

The Poison Pie Publishing House presents:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Portable Library of Hong Samud

(link to main page of novel)

December

|

|

|

|

|

December 1, 2015

On an Inhospitable Reception

“You will waste his noble sacrifice,” said the apprentice to the prospector, “if you return to the city of devils and allow yourself to be captured again.” He said this in earnest for he feared that the headstrong woman appeared intent on rushing out the door, headed for the caves in a foolhardy and doomed attempt to rescue the clerk.

One night had passed since the woman first had woken. They had managed after the hour of midnight to convince her to return to bed to regain her strength, but any sleep had eluded her as her head was filled with visions of the clerk subjected to the torments of the diabolist. After such a restless night, there was no restraining her. The father, who had been standing by silently while the argument raged between the other two, took this moment to suggest to his son that they seek the advice of his brother.

Thus, within a few moments, the three of them were moving in the morning traffic in the direction of the library. The prospector was again draped in the apprentice’s cloak, with the hood pulled over her face. She had put her boots back on, beneath the skirt and flashes of their foreign make were revealed beneath the colorful fabric and the cloak with each step. The apprentice and his father could only hope that they went unnoticed. They kept their heads down and moved hurriedly, without pausing to greet the various familiar faces.

Without incident they arrived at the libraries, where the apprentice and prospector parted ways with the father, who dared not enter either building for fear of the taboos—those of both diabolist and warlord—that lay upon them. He entreated his son to be careful and nodded formally in parting to the prospector.

The apprentice then led the woman into the new library, for he suspected his uncle had arrived some time ago and had already found a seat at the second floor window. His prediction proved correct, though since the uncle had seen them in the alley, he had already hastily descended the stairs to greet them at the entrance.

He was overjoyed by the return of his nephew, for he had feared that he might not see him again. At the same time, he was alarmed that his brother, of all people, had come to the entrance of the library. He was further disconcerted by the presence of a single, heavily cloaked figure, because, of course, if the venture had proceeded as planned, his nephew should have returned with both the clerk and the prospector. That his nephew might have brought anyone else into the library was unthinkable. The librarian suppressed the urge to embrace his nephew and asked, more gruffly than he had intended, “Who is this?”

“Uncle, may I present Execrabilia, the prospector.”

At the sound of her name, the prospector stood at her full height and pulled back the hood. The librarian surveyed her haggard face, the porous, bony horns atop her brow and the anxiety heavy in her eyes. He had observed the woman, if only in passing, when he had seen his nephew off with her party months before. She had greatly changed and he was not sure that the horns were the greatest difference, though surely they were the most likely to hold one’s attention.

“The diabolist has done this to her,” the apprentice said unnecessarily.

“Where is the clerk?” asked the uncle.

“She would not release him,” replied the apprentice.

“You have managed the affair poorly,” said the uncle.

“I know, Uncle.”

“And what was my brother doing here?”

“He helped me tend to the prospector.”

“Your error is multiplied. You should not have gotten him further involved. He has suffered enough on account of these libraries.”

“I am sorry to have disappointed you. I did not know what else to do.”

Of course, much of the librarian’s severity was due to the uneasiness he felt about his own actions in delivering the diabolist’s dish to Hong Samud’s library. That he found an outlet for his anxiety through the expression of his displeasure with one he loved deeply is, one must concede, an all too common human flaw.

“Uncle, we have need of your aid. She insists on returning...” The apprentice said no more, for though they had arrived only minutes before, they were interrupted by a pounding at the door directly behind them. Uncle and nephew had been summoned in such a way once previously by guards of the warlord.

“You were followed,” said the librarian to his apprentice. To the prospector, he said, “Cover your face.” He opened the doors and greeted the guards, who informed him tersely that they were summoned to the court.

Not a word was spoken as they were escorted around the walls of the palace, through a side gate, and into a small antechamber reserved for private audiences. There the librarian found his brother lying on his side. He apparently had resisted his own summons, for someone, surely a guard, had struck a blow on the side of his face. One cheek was covered in not quite dried blood and an eye was already hidden by swelling.

The librarian lowered himself on his crutches to sit beside him, and, stroking his arm, whispered, “My brother, I am sorry to have brought this upon you.”

The uncle managed a weak smile, then grimaced. “Our family is damned. I am thankful only that my wife did not live to see our end on this day.”

The librarian searched for words of comfort. In truth, he doubted that either himself or his apprentice would meet with a summary execution today, for they were under the protection of the diabolist. However, for his brother and the foreign woman there was no such guarantee.

All guards, court attendants and lesser functionaries had exited the chamber when the warlord arrived. He seated himself in the place of honor and examined the quartet before him with a look of undisguised disgust. “Librarian, rise and explain yourself!” he barked, further revealing his fury.

“My lord,” said the librarian, leaving his brother and coming to stand before the warlord. “The expedition did not go as planned. The...”

“Who is that?” he barked, gesturing at the hooded figure. “Remove your hood.”

Once his command was obeyed, the warlord immediately recognized the foreign woman and needed no additional explanation for he could surmise easily enough the manner in which she had passed the months that had elapsed since her departure from his court. “Are there other survivors?” he asked the apprentice.

“Only her, my Lord,” said the apprentice, coming to stand beside his uncle.

“And the foreign clerk?”

“The diabolist chose to keep him,” answered the apprentice.

The warlord attempted to contain his rage. “I am told this is your father,” he said pointing to the bloodied man on the floor.

The apprentice looked over at his beaten father. “He is, though he played no part in...”

“You told me,” thundered the warlord, “that you would rid me of my devil-priestess and instead you and your family have engaged in a treacherous plot to smuggle a genuine devil, horned and horrid, into my capital!” His blood boiled as his face flushed with rage. He rose to his feet, weighing the desire to exercise the violence of his authority against the prohibition of the diabolist.

“My Lord,” said the librarian, bowing his head. “There is no treachery. Since the day I first drew a sword in your service, my loyalty has ever lain with you.”

This testament of fealty placated the warlord only modestly.

“Where is the foreign librarian, he with the supposed power over devils?” demanded the warlord. “I command that you bring him before me. Now!”

Before the apprentice could explain that such an act was beyond their abilities, the uncle moved half a step forward and said crisply, “It shall be done.” He alone knew that he held the clerk’s card, which provided entrance to Hong Samud’s library. Moreover, he had already demonstrated mastery over it, though he took care not to share such information.

Originally, the warlord had intended for the librarian to retrieve the foreigner on his own, but the librarian reasonably explained that he needed his apprentice as a translator, then added that the presence of the foreign woman in her current state would help him make his case. Thus, they left only one individual in the detention of the warlord’s court. From his position on the floor, he watched the other three leave the room with nary a word. Soon, the father was left alone to consider the error of his ways.

|

|

|

|

|

December 2, 2015

On the Summoning of the Librarian

The trio stood outside the small room in the old library. The apprentice watched with amazement as his uncle, balanced on one crutch, produced a library card, similar if not identical to that of the foreign clerk, and swiped the frame of the doorway. The portal obediently responded and his uncle stepped through, without looking behind to see if he was followed.

The prospector proved less willing to enter the portal, for in all of the preparations that the clerk had given her regarding the background of this country, he had entirely neglected to mention the peculiarities of the source of his information.

“We must hurry,” urged the apprentice, who did not know how long the portal would remain open, having only observed it twice before.

In a state of befuddlement, the prospector stepped into the portal and the apprentice followed, almost pushing, behind her, lest he be caught as it closed—a fate he did not want to investigate.

They joined the warlord’s librarian in the central corridor. As soon as the portal had disappeared, he stole a quick glance into the room behind it to confirm that the diabolist’s dish remained on the table where he had left it. Then, he promptly called out in the central hall, “Hong Samud!” as much to summon the librarian as to keep the attention of the others from the dish. He did not wish to partake in any discussion of it, for fear of being forced to reveal his role in its delivery. He led them several steps down the corridor, so that the opening to the room was behind them and the dish was out of sight. “Hong Samud!” he called again.

Some time passed—ten minutes perhaps, it was difficult to gauge—before the arrival of the librarian and his daughter. They appeared around the corner, walking side by side, the diminutive islander and the crow maiden. The two parties stopped at a separation of roughly a dozen feet and allowed themselves to be examined. Each individual had their own response. The warlord’s librarian surveyed the pair and reconciled their appearance with the silhouettes he had previously observed through the portal. His nephew experienced a thrill of exhilaration for he had built up this moment in his mind as a meeting with a master librarian from whom he could learn the deepest secrets of the trade; he looked with some envy at the girl, who moved with ease through these hallowed halls.

The prospector appeared least prepared of all, an unusual situation, as she prided herself on being able to adjust to any locale. Here she found herself utterly out of sorts. She felt exposed, almost as if she had a preternatural inkling of the characteristic of the library that allowed it to create new rooms of books on the subject of each patron who entered it without first asking for their approval.

Hong Samud, for his part, surveyed the three new patrons. Three! Three at one time! His only relief in the face of this invasion was that he could comfortably recognize them as the prospector, the warlord’s librarian and his nephew, based on the descriptions of the clerk.

It fell to the crow girl to react first. She was drawn not to the one-legged librarian or his apprentice but to the ragged state of the prospector, whose ill health at her recent treatment seemed exaggerated by the confusion that now assaulted her. The crow girl read all this in her face and stance. She rushed forward, quickly closing the distance between them, and threw her arms around the midsection of the prospector, burying her head in the older woman’s bosom. “Execrabilia,” she said,

“Anxo found you!”

“What is this place?” she asked the girl as she allowed herself to be held.

The crow girl unwrapped her arms and took a step back. “You stand in the library of Hong Samud.” She turned and looked at the man behind her, “My father.”

This was the first that the warlord’s librarian or his apprentice knew of the supposed blood relationship between the pair; certainly their disparate appearances did not support any kinship founded in biology. Perhaps, more interestingly, the warlord’s librarian was able to understand the words of both the prospector and the crow girl. Thus another trait of the library was revealed—in a mental realm, a sort of telepathic communication accompanied words that allowed all languages to become a single tongue.

“I don’t understand,” said the prospector. “How can this be?”

“It is a perfect library,” said the crow girl. “My father designed it this way.” She gestured to Hong Samud. “Come forward, Agidoda, and greet your guests.”

Greetings were then exchanged and introductions made. Of the horns on the brow of the prospector, not a word was said, though Hong Samud gave them much thought. He had even doubted whether the prospector, given the tales of her diabolical, though distant, heritage, would be able to enter the library, which was impervious to evil, at least evil uninvited. Ironically, these thoughts were also shared by the warlord’s librarian who had witnessed the diabolist’s failure to open the portal. He had assumed a perfect library would not allow the foreign she-devil to enter. However, at this point, the thoughts of the two librarians diverged. For where the warlord’s librarian became disappointed with what he deemed a flaw of this library, the other found cause for joy. Hong Samud implicitly believed in the inviolate perfection of his library; if it permitted the prospector to enter then it could only mean that she, despite her lineage and despite her horns, carried no evil within her. This thought cheered the librarian, who reached out his hands and took within them one of the prospector’s hands, shaking it in an enthusiastic welcome to his library. He needed no further explanations at the moment; later, he would have ample time to investigate at his leisure the rooms created for all three of these visitors.

When he did seek out the story of the prospector’s family, he would find, as many already suspect, only a distant legend of woe. Whatever ancestor had consummated a union with a devilish power had not done so in a heedless pursuit of worldly power and wealth. On the contrary, it had been a young mother in desperate straits, not only abandoned by her husband but neglected by those social institutions that might have aided her in her time of need. Her prayers to the powers of good to feed and shelter her children having gone unheeded, she redirected her pleas to the forces of Hell, where they were heard and answered, for a price: a nine-month rental of her womb. From this inauspicious beginning, a thousand generations of mortal humans proceeded along a path blessed (or cursed) by a hellish boon, which led in time to, among many others, the prospector. That she bore the undeniable genetic stain of devilish ancestry in the biochemistry of her mortal form could not be denied. She had, like some but not all who carry such genes, managed to overcome her bestial impulses and to aim for a life with which many of us might sympathize if not approve—that of getting along, doing the best one can, making ends meet and enjoying, when possible, one’s time with friends. It was therefore not unreasonable for Hong Samud to admire the prospector overmuch, for she had not been predisposed to become one who might enter his library, but she had found a way all the same.

“Our lord has demanded that you appear in his court,” said the warlord’s librarian to Hong Samud. “He wants to know when you will free him from the diabolist.”

“Of course,” said Hong Samud.

“What is your plan?” asked the apprentice with a mixture of apprehension and premature adulation.

“We must get Anxo back,” pleaded the prospector.

“Calm yourselves, all of you,” said the crow girl. “In recent days, my father and I have searched numerous books within the library and have discovered much that is useful.”

The apprentice had once trustingly believed that the clerk had a viable plan. This time he would not blindly follow. “Is it a real plan?” he asked the crow girl. “Not one that simply results in you or your father trading places with the clerk and switching one problem for another?”

Hong Samud considered the suggestion of the apprentice. He had no intention of offering himself to the diabolist in place of the clerk and said so.

“Well, what is your plan then?” asked the apprentice.

“I shall give the diabolist what she desires even more than an angel to disgrace.”

“And what is that?” demanded the apprentice.

The librarian paused for a moment before replying with carefully chosen words. “To prescribe the remedy,” said Hong Samud, “one must first understand intimately the needs of the patient, as if they were one’s own. Do you wish to internalize a detailed description of the needs of the diabolist?” He looked pointedly at the apprentice. “It is not for the faint of heart,” he warned.

The apprentice frowned but he seemed resolved to not so easily give up.

Seeing that the young man was of two minds, Hong Samud spoke again with words that surprised all of them. “Do you see these horns mounted on the head of Execrabilia by the work of the diabolist?”

Of course, no one present needed their attention drawn to the horns. The crow girl thought it rather poor form of her father, but she allowed him to make his point.

“Do you know why the diabolist placed them there?” he asked.

No one answered.

“I shall not tell you,” said Hong Samud. “It is better for you to come to your own realization at a pace that suits you through the circumlocutions of your own minds.” For Hong Samud, the answer was clear and had been confirmed once he understood the goodness within the prospector. She had transcended the limits of her heritage. There must be others among the folk of the diabolist yearning for much the same freedom and attempting the same transformation. The hand of the diabolist had been forced to make an ignominious spectacle of the prospector in order to demonstrate that there was no escaping a devilish heritage. This fear that she was losing control over her people provided the basis for Hong Samud’s plan.

In truth, neither the apprentice nor his uncle possessed even the faintest desire to know more of the diabolist. On the contrary, they wished only to put as much distance as they could between her and their family. Thinking of family, the apprentice said to Hong Samud, “The warlord holds my father while he waits for you to come.”

“Then your father need wait no longer. Let us go.”

|

|

|

|

|

December 3, 2015

On the Librarian’s Audience with the Warlord

A soldier had carried a wooden chair into the chamber, placing it against a side wall. He ordered the father of the apprentice librarian to sit in it, which he now did. Sunken in the chair, he seemed an immobile witness to the exchange which followed. The warlord re-entered the chamber alone and strode to his seat on the dais, paying no mind to the father. Not a minute passed before a group appeared in the entrance opposite the warlord.

They were led by the apprentice. Behind him walking side by side were the prospector and the one-legged librarian. In the rear was Hong Samud. Neither the father nor the warlord seemed to notice the crow girl, as if she was no more conspicuous that the shadow of Hong Samud.

The apprentice came to a stop before the warlord. The prospector moved to one side and the warlord’s librarian to the other. Between them Hong Samud stepped forward. He bowed formally before the warlord.

Hong Samud spoke and the apprentice, standing beside him, translated. “Long have I read of the magnificent architecture of your palace. Now that I see it with my own eyes, I am not disappointed. My understanding is that much of the structure was designed by your grandfather.”

This show of formality was not as the warlord had expected the encounter to proceed. “You are wrong,” he said to Hong Samud. “My grandfather only continued construction along the plans laid by his father.”

“And when this palace passes to your son and heir, its glory shall be further magnified,” said Hong Samud.

The warlord pursed his lips, for the son of which Hong Samud spoke, though dearly sought, had not yet been born. A tender subject, the warlord turned abruptly to matters of business. “Librarian,” he said to Hong Samud, “You have already lost a party to the caves and, in retrieving one of that number, you lost another. I advise you to meddle no further, lest in so doing you lose your own life and stir up the hornet’s nest for those who remain.”

Hong Samud bowed his head as he listened to these words, which, interestingly, were not framed as an order. The warlord knew as well as he did that such was not the course laid before them. “One day,” said the librarian in response, “this land will be free of devils and your progeny will recline in a library in the calm company of librarians, but today work must be undertaken if such a happy occasion is to come to pass. I ask your permission to travel once and only once to the domain of the diabolist. There I shall do what I can to retrieve our missing clerk and I shall no less endeavor to break the chain that binds your descendants to future generations of diabolists.”

This was the warlord’s first indication that his line, and not pointedly he himself, would be the benefactor of the relief, which had been promised. This revelation proved simultaneously disappointing and somewhat reassuring, for only trivial matters could be changed in a night.

“I grant you three days,” said the warlord, “then, regardless of whether you succeed or fail, you and your kind are no longer welcome in my capital nor any of the lands under my domain.” The warlord rose to his feet. “I will order a mule train be arranged so that you may set out immediately.”

The apprentice could have hoped for no better outcome. He turned to escort the group from the warlord’s presence before he changed his mind.

To everyone’s surprise, Hong Samud declined the offer. “I appreciate your gracious generosity on my behalf, but that won’t be necessary, my Lord.”

“How else will you meet her?” asked the warlord.

“I prefer to travel by library,” explained Hong Samud. “I shall return to my home. From there, I will move without delay directly to the subterranean, public library of the diabolist.”

The warlord tried to show no sign of being nonplussed by the announcement of a library in the underground city. Presumably, her dark folk had a full complement of the municipal institutions necessary for the functioning of a city. Still, the idea that a strict prohibition against the public access to books should be maintained in his own city but relaxed under the rule of the diabolist deeply disturbed him.

Before Hong Samud departed he said to the warlord, “I shall require the services of your translator in these negotiations.”

To this the warlord acquiesced with a nod.

“I also respectfully request,” said Hong Samud, “that you allow your librarian to take his brother home. You need hold no surety to secure my loyalty; I shall honor my word.”

The warlord looked down at the swarthy, diminutive librarian. It was not in his nature to trust strangers (or even well-known associates for that matter). Still, he found himself unable to deny the sincerity in Hong Samud’s request. “Very well,” he murmured. In contradiction to court etiquette, he left the chamber first, before the confounded librarian wrangled any additional concessions from him.

|

|

|

|

|

December 4, 2015

On the Wrack and Ruin of Angels

Gentle Reader, I begin this passage with an apology, for I have sought to present a narrative that moves inexorably to the light. While there may be a guilty pleasure in indulging in the macabre, there is, in general, little long-term benefit to either author or reader. However, here we must momentarily venture into the territory of deep tragedy. One supposes that such an excursion will be redeemed by subsequent passages to more than a palliative degree.

First, they placed the ankles of the angel in shackles, connected to each other by a short chain and tethered by a second chain, about twenty feet in length to an iron ring, anchored in the stone floor at center of the main square. Second, they forced the angel to imbibe a sour potion that within a few minutes blinded him. Third, they fashioned huge, crude, wooden wings, about eight feet in length and attached them via wooden hinges to a square board. This board was then fixed to the back of the angel by a series of ropes and cords wound about his shoulders and chest.

The resulting spectacle was then left to its own devices. The angel tried to stand but the wooden wings, weighing over one hundred pounds each, hung at broken angles. When he struggled to move, the tips dragged awkwardly on the floor behind him, while cords bit into the flesh of his shoulders. On multiple occasions, the angel staggered, tripped by the chain limiting his stride and fell beneath the weight of the wings. Regaining his feet, he stumbled blindly about, performing an obscene dance in the soft, fungal light.

The square was filled with city traffic. A circle of onlookers observed him with expressions of morbid curiosity. Because they could not understand the words that emerged in gasps and anguished moans, they assumed he was cursing them, though they were not completely confident that this was the case. Those pedestrians who sought to cut through the obstacle presented by the circle were forced to avoid the erratic lunges of the angel and his careening wings. The more fearless among them shoved the angel away before he injured them in his stupidity.

Every angel has a common name. A favorite angel of the narrator is called the Angel of Heterodox Fantasies, but her joy does not appear in this tale. The angel imprisoned by the diabolist was known as the Angel of the Flying Crucifix. The nature of the suffering of this angel is of keen interest; we shall investigate the subject further. We understand that there is nobility when suffering is undertaken willingly, as a sacrifice for the benefit of others. The diabolist had sought to deprive the Angel of the Flying Crucifix from such redemption by eliminating any purpose from his suffering. He jerked about meaninglessly, surrounded by a crowd of disbelievers, who seemed utterly immune to the message he was intended, by his very being, to convey.

The diabolist had not allowed this angel to meet or to know in any way of the fate of the devil he had come to rescue. Without the knowledge that the devil had been saved, doubt entered his mind. Perhaps, the one he had sought to liberate huddled in misery amidst the crowd watching him, her tongue cut out, unable to communicate. Perhaps, the obscenity of his degradation served no purpose but as a demonstration that this world into which we all are born is no less willing to condone depravity as it is virtue.

Should we attempt to uncover merit, hidden in the brutal torment of a gentle soul?

We understand, through the musings of Hong Samud, the reasoning behind the treatment of the prospector by the diabolist. She feared that her flock might lose their faith. Her motivation in the destruction of the angel was less clear. Perhaps, it served only the obvious purpose of displaying to her people that the infallibility attributed to angels was a myth. Surely, she could have chosen less gruesome methods to illustrate her point. That she went to such an extreme to humiliate the angel supposes an additional motive, perhaps one she did not choose to admit, even to herself.

No one in the crowd could stomach the horror wrought in the Angel of the Flying Crucifix for long. As his cries of pain echoed in the cavern, the plaza slowly emptied. Families returned to their homes, where they shuttered the windows and barred the doors, in a vain effort to block the sound and erase the memory.

By and large, the residents of the subterranean city feared the diabolist no less than did their counterparts in the capital above ground. The underground denizens, however, labored directly beneath her shadow and were reminded on a much more frequent basis of the cruelty inherent in their origin.

As for the angel himself, he groaned as the rope rubbed his flesh raw and the board cut into his back. Defiantly he rose to his feet again, he rolled his shoulders despite the agony, lifting the wings, if only momentarily, into the air. Already tinged with the perverse delight of madness, his incoherent shrieks traced the outline of a plea for succor, but he knew that no relief was forthcoming, for who would be so foolish as to follow an angel into a pit of devils?

|

|

|

|

|

December 7, 2015

On Putting the Plan in Action

They traveled as a group of six under escort to the old library. The prospector again donned her hood so as not to draw more attention than their unusual assemblage already would. At the entrance they parted ways, for the apprentice’s father maintained his adamant refusal to enter the building.

Surrounded by a crowd of guards, the apprentice embraced his father and asked his uncle to take him home and tend to his injuries. The warlord’s librarian agreed to do so but before he left, he surrendered the clerk’s library card to the prospector, saying via his nephew, “This does not belong to me. He might yet need it when you have secured his release.”

The prospector accepted the card without reply and they watched as the two brothers departed, side by side, one on crutches, the other clutching half his face, down the alley. The guards remained outside the entrance, even as the other four entered the library.

With lantern in hand, the apprentice led the prospector, the crow girl and her father through the aisles of books to the small room in the rear. There, without fanfare, Hong Samud opened the portal and led them back to his library.

Once back in the security of his home, Hong Samud took a deep, satisfying breath of the illuminating air. The prospector pulled back her hood, revealing her disfigured face; there was no call to maintain illusions in the library of Hong Samud. He showed the prospector and the apprentice librarian the curious dish that he and his daughter had discovered left in the library.

The prospector thought it an unusual oddity, but had little patience for it since she did not understand its relevance to them. The apprentice on the other hand recognized from his studies of unholy texts that this offertory plate had belonged to the people of the diabolist. He had not thought to find the work of her dark folk in this perfect library; he waited for the librarian to explain further.

“It turns out,” said Hong Samud, “that there are two numbers on the other side.”

“Numbers for what?” asked the apprentice.

“It took a while to figure out,” admitted the librarian. He looked at the crow girl, “And a little inspiration.”

“We think they are numbers to portals in this library,” she said.

“How is it possible?” asked the apprentice. What he really meant to ask was, “How is it possible that the diabolist even knows of this library?” He truncated his question because he suspected most uncomfortably that he himself was responsible for divulging the existence of this library to her. Surely, he thought, he had not given her sufficient information during his interrogation to map out the rooms; he possessed no such knowledge himself. He looked nervously at the librarian. Fearing that he would be upbraided, he mentally composed arguments to defend himself—he had spoken only under the threat of torture!

However, Hong Samud requested no justification. Instead, the crow girl spoke again, “One must understand, Hassan, that there are an infinite number of fellow librarians who have willingly pledged themselves to the task of maintaining this library. These collaborators are very difficult to locate. My father claims to have never encountered another one, though I am not so sure.” She let an innocent smirk play across her face. “In any event, we feel fairly confident that this dish directs us to two doors in the library.”

“Doors to where?” asked the apprentice, wondering only briefly who had shared his name with the crow girl.

“The destination of the second door may be revealed in good time,” said Hong Samud. “But the first door is where we go now, for I believe it leads to a library in the city of the diabolist.”

As the quartet walked along the central corridor, the prospector and the apprentice received their first tour of the facility and were somewhat overwhelmed by the immensity of the suggested infinite dimensions of the library.

“Is all knowledge contained here?” asked the apprentice.

“The multiverse itself,” answered Hong Samud, “is not vast enough to contain all knowledge. This structure serves as a repository for a sufficient subset of information, from which one can draw the necessary conclusions needed to guide one’s future actions, nothing more.”

The prospector felt that they walked for quite some time through the never-changing landscape of doorways to book-filled rooms. It proved easy to ignore the small numbers on the brass plates and to think of their passage as lacking any progress at all. Abruptly she announced, “I am afraid to return to the dark city.” It was decidedly uncharacteristic of the prospector to admit her insecurities to herself much less others, an indication of the extent to which the library unsettled her.

The crow girl slowed and dropped back. She fell in step with the prospector and wrapped both hands around one of the woman’s lean arms, clinging to her in a way reminiscent of a child, while they walked. The apprentice found this attention very unusual since there was little child-like about the girl other than her youthful appearance. She rather projected an aura, ambiguous but certainly ancient.

“Of course,” said Hong Samud, “Fear is a necessary ingredient for courage, just as doubt is essential for faith.” Leading the group, he turned and met the gaze of the prospector, “So, I ask you to have faith in me.”

He led them to the room bearing the first number deciphered from beneath the dish. Upon cursory inspection from the central hall, the contents of the room seemed indistinguishable from those in any other room. Hong Samud did not wait for anyone to express their reservations.

He swiped his flimsy, temporary library card and the portal opened. He stepped through, demonstrating a bravado, which he did not necessarily feel but which he hoped was contagious all the same.

|

|

|

|

|

December 8, 2015

On Hong Samud’s Visit to the Underground City

The dark folk of the diabolist delighted in the arts. The library into which Hong Samud and his companions entered served therefore as much more than a lending place for books. It also showcased the work of local artisans, worked semi-precious gems faceted in unusual ways, stone sculptures in which the play of light in the veins of mineral color gave movement to the forms, or the weaving of ornate patterns in rugs and quilts. The artwork seemed evenly distributed between subjects sacred and profane, conveying both whimsy and dread.

Hong Samud led his companions into a central gallery of the library, adorned with decorative arts and lined on one side by a row of tables at which seven or eight children were diligently reading. These children, as with all of the dark folk, possessed fine hair like white spider silk, gray skin not suitable to prolonged exposure to the sun, and a final mark of their genetic heritage—pinched and pointed ears. They murmured among themselves as the strangers emerged from the back of the library, though they remained in their seats. Their teacher, one must supposed, skittered quickly across the floor and through an exit, presumably to alert the authorities to the unannounced arrival of visitors.

Hong Samud slowed his pace, ostensibly to examine the sculptures at his leisure, though he hoped this would give the opportunity for the local librarian to approach them. No such librarian appeared. In fact, contrary to the expectations of the apprentice and the prospector, no one appeared to escort them from the building, particularly no guards. The quartet therefore wandered at their own pace into the antechamber, which led to the street.

Word had clearly spread of their arrival. Adults, alone and in pairs, appeared at the doors to shops and homes along the avenue, eager to catch a glimpse of the visitors but also careful to keep their distance, for each of these residents had a relatively clear idea of the misery that awaited them.

Hong Samud tentatively made his way down the street. He asked the apprentice for directions.

“To the main square, I suppose.” Above the roof line, the apprentice spied the columns rising to the ceiling of the cavern, in which the temple of the diabolist lay. He had no desire to return to the site of his betrayal, especially in the company of Hong Samud.

As such, they emerged at the edge of the plaza, which held at its center the gruesome spectacle of the Angel of the Flying Crucifix. The angel, at this moment, lay collapsed in a heap, his wings folded roughly over on the stone beside him.

The sight proved too much for Hong Samud to bear without action. His intentions must have been obvious to the crow girl, for she took hold of his wrist and restrained him from crossing the plaza and going to the aid of the angel.

“That is not for you, Agidoda,” she said in a whisper.

The prospector had already moved forward. She broke into a run across the plaza. None of the more than two hundred witnesses lined around the edge of the square moved to intercept her. She knelt beside the angel and cradled his head in her lap. What words passed between devil and angel were known to them alone.

“The diabolist comes,” said the apprentice to Hong Samud.

Indeed the diabolist now moved at an angle across the plaza toward the librarian. She could not be unaware that the devil on whom she had planted horns had returned to her, as she had predicted to her people. She did not allow her delight to be known that, in doing so, the prospector reiterated the enduring message of the diabolist: this city was a haven for devils, a sanctuary like no other.

The diabolist reached the librarian. She glanced briefly at the apprentice who stood to his left, prepared to act as translator. She seemed oblivious, as the warlord had been, of the presence of the crow girl on his right. “Hong Samud,” she said in greeting. “I have been expecting you.”

The apprentice translated, as Hong Samud produced a slight bow. “Gyermek,” he said in reply, “you honor me with your reception.”

The diabolist no longer took affront at her name being used so casually. The trials of the angel had shown her that such transgressions led to their own more than satisfactory penance.

“I thank you for returning my devil to me.” She turned and observed the tender exchanged between the prospector and the clerk. “They make a lovely pair, do they not?”

“They do,” Hong Samud whole-heartedly agreed. “But, though I indeed sought to reunite them, it is not my intent to leave them in your care.”

“What can you offer me in trade?” asked the diabolist in a mirthless tone.

At that moment, the children from the library appeared at the edge of the plaza to witness the exchange. One of the children, a girl, exclaimed aloud, “The devil is cutting the wings off the angel!” Her observation proved accurate. The prospector had brought a knife with her, stolen from the house of the apprentice’s father and concealed in the clothes of his mother, for she had not renounced the need for violence should it come to that. With this knife, she cut the cords that bound the wooden wings to the clerk’s back. When the last strand was severed, the angel groaned and the wings clattered lifelessly to the stone.

The diabolist seemed not perturbed at all by the events unfolding behind her.

Hong Samud gestured with an open palm to the girl who had called out. “Is that your daughter?” he asked in a pleasant tone.

The diabolist froze. Certainly, the chain of priestesses could not be broken. That she had a daughter was a necessity though it was a subject of which no one was permitted to speak, for there could be only one priestess at a time. The child had been taken from her at its birth and raised unseen, indoctrinated in the ways of the diabolists by the crones of the temple. She replied in a steely tone, “No.” In a single question, her mood for civil banter had evaporated. “You have come here empty-handed. So you will leave.”

Hong Samud nodded apologetically. “I am afraid you misunderstand me. I have not come to idly waste your time. I have a proposition for you.”

The diabolist waited for him to continue.

Hong Samud gestured to the apprentice. “I thought that we might continue the conversation in my library, where we could communicate directly, without need of an intermediate.”

Although the diabolist did not understand how a library could bridge their language gap, she felt no curiosity about it. “No, state your proposition here. What do you offer?”

Hong Samud smiled, almost bashfully. “I offer you only what your heart most desires—what all hearts most desire.”

The diabolist did not reply but waited for the librarian to continue.

As Hong Samud spoke, he paused at the end of each sentence while the apprentice translated his words. The librarian had imagined this conversation taking place in his perfect library. He was somewhat disconcerted that he left the choice of words in such a delicate negotiation to the young apprentice. He need not have feared, for the apprentice was well-versed in the language of Hong Samud and provided an impeccable translation.

“Each of us,” said Hong Samud, “desires the confirmation that our time has been well spent, that we acted in accord with our vision of our purpose. When we lie in bed at night, contemplating the events of the day, we would like to sleep soundly in the knowledge that our efforts were not squandered, that our time was not wasted in pursuit of hollow goals. For those like you, diabolist, and I, useless librarian, who labor in work the value of which is not immediately recognizable, it is especially essential to know that one did not engage in an endless sequence of errors, some trivial in nature and others egregiously so, as a result of a colossal misunderstanding. As such, I offer you the opportunity to absolve you of your uncertainty.”

The diabolist had listened patiently, though her unease grew. When the apprentice finished rendering the last phrase, the expression of the diabolist made no mistake in conveying that she remained unconvinced. “How can you deliver such an impossible promise?” she scoffed.

Hong Samud took no offense at her tone. On the contrary, he intoned, almost solemnly, “You shall be held in the hands of the lord you serve and he shall read you like a book; every moment of your existence shall be revealed to him. When he has finished reading and he closes you, he shall judge your actions. At that time, you shall know with perfect clarity the truth of your ways. Is that not what you want?”

The diabolist did not reply.

“Or,” said Hong Samud, gesturing at the angel leaning into the embrace of the prospector, “do you prefer to remain here, directing grotesque acts of questionable merit, saved from a paralysis of uncertainty only by the brute inertia of precedent? Is this the tradition you intend to pass on to your daughter?”

To be sure the diabolist had never met someone as peculiar as Hong Samud nor engaged in a conversation remotely similar to the one into which he had drawn her.

“You don’t have that power,” she said.

“I don’t ask you to trust me,” said Hong Samud. “I ask only that you allow me to show you.”

“They will remain here,” said the diabolist, gesturing with a backward flick of her fingers toward the angel and devil behind her.

“Until you are satisfied,” said Hong Samud.

“Show me,” ordered the diabolist.

“I must take you to my library.” Hong Samud gestured and the diabolist took the lead. He, the apprentice and the crow maiden followed behind. They passed in silence out of the square, retracing their steps through the streets to the library. She led them into the main gallery where they found the books of the students abandoned on the row of tables. Hong Samud motioned toward the room from which they had emerged.

Arriving at the door, he pulled even with the diabolist. He withdrew a bird-headed coin, a gift from his daughter, and handed it to the apprentice. “Librarian,” he said to the young man. “Follow my daughter to my library. Put this coin in the offertory plate and invite the diabolist inside.” In this way, Hong Samud opened the path for evil to enter his perfect library.

The diabolist was astonished to find a young girl beside Hong Samud. It seemed impossible to her that she could have failed entirely to observe the girl before. She watched as the girl with feathers tangled in her hair swiped a card along one side of the door frame. The portal opened, though the diabolist could not see it, because the invitation had not yet been extended. The girl and the boy disappeared inside.

The diabolist stood beside Hong Samud, attempting to ascertain the extent of his apparently considerable powers. She could not imagine him chained or caged in the plaza like the angel or the devil. In fact, she could not imagine any use for the librarian at all.

|

|

|

|

|

December 9, 2015

On a Lost Opportunity

It took some time for the crow maiden and the apprentice to walk from the portal, connected to the underground library, to the room leading to the warlord’s library, where the uncle of the apprentice had left the offertory plate. Once there, the apprentice looked toward the crow girl, who, with a nod, encouraged him to carry out Hong Samud’s instructions.

The apprentice librarian stepped forward and laid the coin, face up, in the center of the dish. There was a clink as the metal touched the ceramic surface. He said to no one in particular, “I invite Gyermek the diabolist into this library.”

A shadow of doubt passed across the face of the crow girl. They had done as they must, though she still harbored great reservations that Hong Samud’s plan should turn out as they intended.

Standing in the underground library beside the diabolist, Hong Samud waited silently. He thought that the woman shifted her weight from one foot to another as a show of impatience. He could not explain the nature of the delay since the translator had already left.

No notification was provided to him by any supernatural means when the apprentice voiced the invitation. Therefore, some additional time passed before Hong Samud concluded he should open the portal and see if it had become accessible to the diabolist.

He swiped the card and was reassured to observe the eyes of the diabolist widen in response. For the first time, she saw the portal. Hong Samud gestured for her to enter. She gingerly stepped forward. In other circumstances, Hong Samud would have taken her hand and led her inside, but he knew from his readings that touching the diabolist was a crime which demanded capital punishment.

He allowed her to proceed at her own pace. She stepped into the library and Hong Samud, hurried after her, the portal disappearing only moments later. Standing with his guest inside the central corridor, Hong Samud was resolved to no longer think of her as the diabolist nor of himself as the librarian. They were now merely two different people, one man and one woman, attempting to reconcile their differences.

The woman looked with curiosity at the room full of books occupying the space behind the doorway where the portal had stood only moments before. She poked her head inside. As the man watched her, she crossed the corridor and made a similar, cursory inspection of the opposite room. She then peered up and down the corridor as it curved out of sight.

“It leads to more rooms,” Hong Samud told her.

The woman, Gyermek, had already been alerted to the fact that all tongues were one in this library. Nevertheless, hearing the man speak fluently in her native tongue—not that of the warlord, but that of her own people—unnerved her. She replied, “I understand you.”

“It is a characteristic of a perfect library,” said Hong Samud, “that there can be no miscommunication.”

Having completed her preliminary inspection, Gyermek asked, “Where do we go?”

“It depends on you,” answered Hong Samud. “I have a particular destination in mind, but there is another secret of the library that I wish to share with you first.”

The woman waited for Hong Samud to continue.

“Every visitor who enters my library brings with them all the books they have ever read or will read. Rooms are created upon their first arrival. These books provide a complete story of their lives including many details of which they themselves might not be aware.”

The reaction of the woman to this news was much the same as that of the crow girl—an indignation to the point of revulsion at the utter violation of her privacy. However, unlike the crow girl, this woman did not allow her emotions to take hold of her. She fixed the man with a rigid gaze.

“Would you like to visit your rooms?”

“For what purpose?” asked Gyermek tersely.

Hong Samud shrugged. “Perhaps, it will provide to you an alternative perception of yourself and your role, framed within a larger context.”

“You seek to sabotage my convictions by sowing doubt,” accused the woman in a dispassionate voice.

“Perhaps,” admitted Hong Samud. “Perhaps, I am hoping that by making this offer I allow you to find for us a different path than the one we seem set upon now.” He shrugged. “Anyway, it is only a suggestion. By no means will I attempt to coerce you.” He added as an afterthought, “It can be jarring to see oneself described without pretense or sensitivity to one’s insecurities and foibles.” He said no more while he waited for her to reply.

“If I choose not to visit the rooms that I have brought with me,” said Gyermek, “where then do we go?”

“There is a book that I would like to show you. It lies in another library. I will lead you to it.”

Lit from all sides by the atmosphere of the perfect library, Gyermek could not explicitly understand the significance of the choice, which she now faced, but seemed to sense its vital importance all the same. She had no reason to trust the soft-spoken man, who to all appearances seemed to express concern for her welfare. Ultimately, her decision came down to an individual choice between holding to the beliefs that had supported her all of her life or abandoning everything she had held true and casting herself without compass or anchor into the unknown. One should not judge Gyermek too harshly for the choice she made. Many of us, in a similar circumstance, would have reached the same conclusion.

“I do not want to see the rooms you claim that I brought with me. Show me the book that was our purpose in coming here and then promptly return me to my people.”

Hong Samud had expected nothing else; this story was already suffused with a premonition of inevitability. His hopes for an unexpected escape had been nothing more than an exercise in wishful thinking, temporarily postponing that which could not be avoided. With no show of the resignation he felt, Hong Samud turned and led the woman down the central corridor.

As they walked her eyes scanned room after room, though she did not stop to inspect them nor did she ask any questions. They walked in endless overlapping circles until from one room, the apprentice and the crow girl, hearing their approach, stepped forth. The two pairs came to a stop several feet from each other.

Gyermek met the gaze first of the apprentice then of the girl. She noticed in the open doorway to her right, resting on a wooden reading table, the offertory plate, which she had had delivered to the warlord’s librarian.

“I am taking her to another library,” said Hong Samud, “to read a book.”

“Should I go with you?” asked the apprentice. “Or will that library also dispense with the need for a translator?”

“I appreciate your offer,” said Hong Samud with a kindly smile. “In fact, we will not be able to understand each other when we leave this library, but we will have no need of your capable services all the same. In fact, you should go home now and see to your father.”

The apprentice librarian was surprised and more than a little disappointed. He had hoped to see things to their resolution, but it was not his place to do so. Hong Samud stepped to the right and swiped his card. The portal to the darkness of the warlord’s old library appeared.

Unprepared for this sudden dismissal, the apprentice faltered. He turned to the crow girl for support. “I...I...” Unable to compose himself, he turned to Hong Samud. “Will you visit my library again?”

Hong Samud shook his head.

Perhaps to console the boy, the crow girl took him by the arm and said cheerfully, “I’ll come visit you in your new library.”

While this statement made little sense to the apprentice, he was forced to accept it.

The crow girl leaned forward and whispered something else in his ear, before releasing him from her grasp.

The content of this message remained a mystery, as if a secret shared between children. The apprentice formally bowed to all three and departed through the portal, which closed behind him.

When he was gone, the crow girl asked, “Agidoda, should I come with you?”

Hong Samud shook his head again. “No, I think not. Gyermek and I will do this on our own.”

He turned to the doorway of the room opposite the one by which the apprentice had vanished.

“By coincidence,” he said to Gyermek, “our destination lies right beside that of the boy.”

He swiped the card and opened the portal to the library of the Normal University of Hell, Phlegethon Campus.

|

|

|

|

|

December 10, 2015

On the Fate of the Diabolist

Gyermek’s senses were assaulted by chemical fumes and a palpable sense of oppression as soon as she stepped through the portal, just as Hong Samud’s had been during his first visit to Hell. That he knew what to expect this time helped him adjust only modestly. In the dim light of the covered lamps mounted on far wall, Gyermek surveyed the wicked barbs that extended from the shelves forming the narrow aisle before them. She scanned only briefly the rows of black-bound books reaching from floor to ceiling.

“Where have you brought me?” she asked Hong Samud, forgetting that, in leaving his library, they could no longer communicate with each other. The echoes of her question were suffocated by the heaviness in the air. She turned and examined him framed in the arch described by a pair of simian arms and a gargoyle head atop it. On his face, he bore an expression of terrible remorse. It took only a moment for Gyermek to understand that she had been betrayed.

Alerted by the woman’s voice, the winged devil-librarian appeared at the end of the aisle. She rustled her wings, drawing Gyermek’s attention from Hong Samud.

The devil reveled in the undisguised terror that appeared upon the woman’s face. Although the diabolist had spent her entire life, beginning at the moment of her conception, in the service of a devil, it was quite another thing entirely to greet a devil face-to-face and perceive without the filtering aid of the limits of one’s imagination the reality of a creature reconciled to an eternity of torment.

The devil closed its wings, so that this time they did not tear against the barb-lined corridor formed by the aisle. She moved with purpose though without haste toward her visitors. Her skeletal arms, ending in oversized claws, hung limply at her sides.

Paralyzed, as if by a spell, Gyermek observed the inexorable approach of the devil. It took all of her will simply to whisper, “Hong Samud!” as if by doing so she might prompt him to call off this dreadful exercise and return her, whole, to the safety of her underground city.

Hong Samud did not act to save her or to save himself. The conclusion of this passage had already been written.

The devil-librarian stopped directly before Gyermek. Carefully, almost tenderly, she wrapped her claws around Gyermek and drew the helpless woman into an embrace until she was pressed tight against the devil’s chest. The wings slowly slid forward and wrapped around her, until she was cloaked in darkness and infused with the chemical stink that lay heavy on the devil’s skin.

The devil looked over its burden at Hong Samud and, by means unknown to him, conveyed a business-like response, as if acknowledging the receipt of some goods, which completed their transaction. His role completed, Hong Samud was dismissed.

He did not immediately activate the portal and flee, though he desired greatly to do so. Instead, he bore witness as the devil-librarian dragged within the cocoon of her wings the unresisting Gyermek.

He stood for some time in the library after they turned the corner and disappeared from sight. He heard their footsteps descend into the basement, where Gyermek would be flayed, her skin tanned to form the leather cover of a book, into which the soul of her being was deposited. This book was titled, “The Prolonged Misfortune of Gyermek the Diabolist”. It would, in time, be placed among the other books stored in this library.

What delayed Hong Samud’s return to the library was his deep dissatisfaction with himself. He could imagine no possible interpretation by which his actions had not ruined the perfection of his library. He experienced acutely the agony of his own inadequacy and the guilt of his failure.

When he did return to his library, he found the crow girl waiting just beyond it.

She smelled the stink of Hell on his clothes. She read on his face his dire judgment of himself. She offered no immediate comfort, allowing her father time to compose himself.

Hong Samud remained unmoving outside the doorway after the portal had closed. “This reminds me of a passage in a book I read long ago,” he said abruptly to the crow girl.

Although the crow girl knew well of her father’s love for books, she had not expected such a comment at this moment. “Tell me,” she said, curious as to what had come to her father’s mind.

He said, “At the beginning of the third century A.D., there was a chancellor of the state Shu Han, who was recognized as the greatest and most accomplished strategist of his era. His name was Zhuge Liang, though he was called Kongming. On one occasion, Kongming found the forces under his command greatly outnumbered by an army from the Black Lance Kingdom. He engineered a trap, in which the enemy was confined within a valley, where they perished to a man, through a combination of incineration and pulverization by missiles launched from above. Kongming’s thoughts on the victory are recorded as follows:

“This trick,” Kongming told his commanders, “I used only because I had to; I shall lose much merit in the life to come for it.” †

The crow girl cast a sad smile at her father. “Don’t fret so, Agidoda,” she said. “We are not yet finished with our own trick.”

†Three Kingdoms, attributed to Luo Guanzhong (1330-1400 A.D.), trans. Moss Roberts, Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, 1991, Vol. 3, Chap. 90, p 1080.

|

|

|

|

|

December 10, 2015

On the Angel and the Devil

No one in the underground city, including the prospector, knew that the diabolist would not return. In truth, only one person on that side of the world was aware of this fact—the apprentice librarian, for when the crow girl agreed to come visit him, she had added in her whisper that she would come alone because neither Hong Samud nor the diabolist would ever travel through that portal again. It was true that, in time, the apprentice librarian shared this secret with his uncle and with the warlord, but there was no means for this message to reach the dark folk of the diabolist. Their understanding would come only in the form of a period of waiting that remained permanently unfulfilled.

This mattered little to the prospector. She had no intention of waiting. Hong Samud and the diabolist had been gone only a few minutes, when she managed to bring the blinded clerk to his feet and then only by supporting him with an arm around his back. She virtually carried him along the plaza.

The hundreds of witnesses did nothing to stop her. She was, after all, a horned devil; who were they to block her will? Besides, as we noted earlier, the spectacle of the Angel of the Flying Crucifix was, after its initial shock, judged to be as abhorrent to them as it would have been to any of us. They had reached a collective consensus, without need for public discussion, that it was best if both devil and angel left the city and were never seen again.

Therefore, the prospector encountered no obstacles, save the exhaustion of the clerk, in reaching the library and passing through the gallery to the far doorway that served as the portal. She took the clerk’s library card from her pocket and swiped the doorway, uncertain if she would require the clerk’s assistance to get it to function properly.

She was pleased to find that the portal opened instantly. She spared a moment for a silent thought of gratitude to Hong Samud for his diligent care in the preparation of his library. The prospector hauled the clerk through the portal to the safety of the library.

Gentle Reader, it may be difficult to keep in place the relative locations of all of the various portals within a library that defies geometry. All that is necessary at the moment is to recall that the room leading to the dark city was far from the rooms where the crow girl waited for Hong Samud to return from Hell. Thus the entrance of the prospector and the clerk remained, for the time being, unknown to the librarians.

Not knowing what else to do, the prospector dragged the clerk through several revolutions of the central corridor, until, exhausted, she guided him into a side room, chosen at random, and lay him as gently as possible on the stone floor. She collapsed in relief beside him.

Time was immeasurable in the library of Hong Samud.

When the prospector woke, she found the clerk still asleep beside her, his head propped on a pillow. Draped over them both was an open sleeping bag. She recognized these as her own gift to the librarian’s daughter.

The prospector wondered only briefly as to how they had been found, for when she eventually stepped outside the doorway, she discovered a sporadic trail of drops of blood leading to the room, from the wounds where the cords had cut into the clerk’s shoulders. She found more of this blood dried on her own hands and clothes. She returned to the clerk and lay down beside him, rearranging the sleeping bag to cover them both, before she nestled against him and went back to sleep.

Much later, when asked by subsequent patrons about the blood stains on the hallway floor, the crow girl would have occasion to explain, “This is the Trail of the Injured Angel. We proved unable to remove all traces of his passage.”

After a much shorter expanse of time, the clerk and the prospector rose, rejuvenated. Their bodies had healed in the sanctuary, though the clerk’s sight was not yet completely restored and the prospector’s horns remained.

“Where do we go, Anxo?” asked the prospector.

The insurance clerk seemed completely at ease with the realization that he woke in the company of the prospector in the library of Hong Samud. “I only know the destination of one door,” he said, “The doorway numbered three thousand one hundred and seventy-two will take us back to Sigil.”

“Is that where we are headed?” asked the prospector. “Back to the insurance company?”

“Execrabilia,” said the clerk, “I must confess that the company fired me.”

The prospector laughed at the grave manner in which the clerk admitted his dismissal.

Thus it came to pass that, when Execrabilia and Anxo were ready to leave the library, they did so via another portal, one chosen at random, on the basis of an unfounded optimism that their shared future would be bright.

|

|

|

|

|

December 11, 2015

On a Trio of Dark Gods

The second number inscribed on the underside of the offertory plate led to the most pitiful library Hong Samud had ever visited. It was scarcely larger than an outhouse; the confines were cramped even when occupied only by the crow girl and himself. Within the wooden shack, there was no librarian nor any furniture. A single book rested on a shelf attached to the side wall. The cover appeared so filthy that not only was the title illegible but Hong Samud did not want even to touch it. The crow girl therefore reached around him and lifted the cover exposing the tattered title page. She read the title, “On Librarians and Their Various Uses”, to Hong Samud.

Judging that he knew very well the nature not only of his usefulness but of his uselessness as well, Hong Samud wanted nothing to do with the book. As the crow girl closed it, Hong Samud peered out one of the numerous gaps in the planks of wood that formed the walls of the library. The light that shown through reminded him of the purple light he had experienced in the ornithological library of the crow girl, though this light possessed a maroon hue.

The crow girl opened the door and stepped out of the library with Hong Samud close behind. The features of this landscape were indistinct, reminiscent of a dream. In all directions, the distant horizon was clouded in fog. The surface beneath them was solid, but afterward if questioned on the matter, Hong Samud would have been unable to recall whether it was rough stone or a tiled floor.

The only clear feature to Hong Samud was the silhouette of three figures seated around a table several hundred yards in the distance. He walked beside the crow girl toward these figures.

It turned out that he had under-estimated the distance between himself and those seated at the table because he had assumed that they were human-sized. In fact, they were all three gigantic, at least double, perhaps triple the size of an ordinary man, much less the diminutive librarian.

As he drew closer, Hong Samud surmised that the trio was playing cards, although in a most laconic manner, as if none of the three had any interest in the outcome of the game. The features of the three giants were cloaked in shadow, as if they stood beneath an invisible tree, present only by its ability to block the maroon light.

Of course, these three constituted the trio of dark gods that ruled the lands of the warlord. One of them, the sadistic devil, who reveled in the misfortune of others, was the lord of the diabolist. At their approach, he rose to his feet and turned his back to the table. The other two, a demon of insatiable appetite and an ambiguous god that could not distinguish good from evil, remained seated, though their attention was diverted from the game to the business of their companion.

The devil focused his penetrating gaze on the crow girl. Just as the warlord and the diabolist had seemed oblivious to the presence of the crow girl, so too did this dark god ignore Hong Samud, as if he were a wooden puppet manipulated by the crow girl, standing a few steps behind him.

Hong Samud said, “Your servant, Gyermek the diabolist, has been donated to the library of the Normal University of Hell, Phlegethon Campus. I humbly recommend that you check out her book.”

The devil said nothing but continued to examine the crow girl. She showed no fear, for she was a million years old and this was not her first foray into ancient dangers.

The devil gestured, the merest shift of a taloned pinkie. It was enough to dispel all illusions. The crow girl was revealed in her inhuman majesty, wings and all. Her appearance did not take Hong Samud by surprise for he had, from the beginning, accepted that his daughter was not of his own seed.

As for Hong Samud, his illusionary appearance was also dispelled. He was no longer a swarthy, equatorial islander nor a retired scholar. Instead he became a superposition of an infinite number of librarians all centered at the same point. In the explosion of color and motion, he appeared to the crow girl only as an amorphous man-sized glimmer of light.

The devil seemed satisfied with his observation. He turned and rejoined the card game.

The purpose of their mission completed, Hong Samud and the crow girl returned to the library shack and reactivated the portal. Upon emerging in the central corridor, they found each other in their familiar forms—any previous perception was thus saddled with the doubts associated with the fleeting vision of dreams.

Neither Hong Samud nor the crow girl possessed any means of knowing whether the dark god visited the library in Hell and read the book of the diabolist. Hong Samud imagined that such a visit indeed transpired. He imagined Gyermek held in the massive hands of her lord. He imagined the penetrating gaze consuming every character in her book. Perfectly exposed, the communion between mortal and immortal, of which Hong Samud had promised, was made manifest. Validated, Gyermek was able to accept her suffering as justified and noble. Hong Samud imagined these things because doing so helped him repair the damage he had, in his clumsiness and ineptitude, done to his library.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This work is made available to the public, free of charge and on an anonymous basis. However, copyright remains with the author. Reproduction and distribution without the publisher's consent is prohibited. Links to the work should be made to the main page of the novel.

|

|

|

|

|

|