|

|

|

|

The Poison Pie Publishing House presents:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

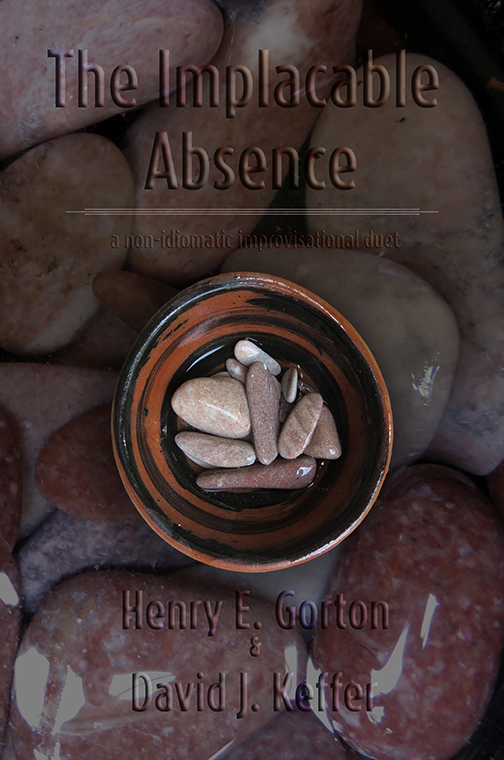

The Implacable Absence

A Non-Idiomatic Improvisational Duet

Henry E. Gorton & David J. Keffer

(link to main page of novel)

June

|

|

|

|

|

June 4, 2014

As revealed in accounts of Elder Faerie, narkrïmá is spun from equal parts flax, spider's silk and ether. Both material and abstract, it serves many purposes. Celia observed Princess Pie set down her star lantern in order to brandish a small knife with which she deftly cut fabric from a white petal of a flower, larger than either of the faeries. With a wave and a flourish, the fabric wrapped around Celia and was stitched with narkrïmá. In a matter of moments, Celia wore a simple shift identical to that donned by Princess Pie.

“Wonderful,” said Celia, admiring the light and supple feel of the gown.

“You look gorgeous!” announced Princess Pie in an approving tone. She turned to Poison Pie and Tchict’Ict, both decidedly less pleasing to the eye, and asked pointedly, as if the two witnesses should have offered their compliments without her prompting, “Doesn’t she?”

“Absolutely!” Poison Pie hurriedly agreed.

“Gorgeous!” repeated Tchict’Ict, then thinking this parroting of Princess Pie’s judgment not to be enough, added, “Two peas in a pod!”, which pleased Princess Pie inordinately.

Poison Pie cast an envious look at Tchict’Ict, wondering where along the journey the insect man had suddenly developed social graces.

Before departing the flower from which the material had been cut, Princess Pie stitched the petal back together into a shape that was different and certainly smaller than before but no less healthy.

They followed the bobbing star lantern further into the forest, stopping at a small clearing filled with a variety of pitcher plants known only in Faerie. Like all of their kind, these plants possessed water-tight cavities filled with liquid. Unlike their kin on Earth, which held an acidic broth designed to decompose hapless insects trapped within, the faerie pitchers possessed a nectar with a variety of potentially ambivalent purposes, not all of which were known, but none of which involved acidic decomposition.

The weight of a faerie was enough to tilt the pitcher on its stem, allowing Celia and Princess Pie to drink. Tchict’Ict, nimble and dexterous, crouched low to the ground, tilting his neck at a distinctly peculiar angle and likewise partook of the nectar, discovering that it both replenished his store of energy and dulled his numerous senses. Poison Pie, ungainly and lumbering, attempted to grasp the stem of a plant in the clumsy grip of his mitt, only to tear the plant from its roots, which earned him a scathing look of condescension from Princess Pie.

“You don’t have to kill something to enjoy it,” she scolded him, as if reprimanding a backward barbarian. Even Tchict’Ict seemed to roll his pupil-less eyes.

Poison Pie frowned and gazed into his floral cup, his interest in the contents now spoiled. It would be worse to waste it, he knew, or thought he knew.

In Faerie, the world is simultaneously big and small. One understands that one is a speck among a nearly infinite number of specks distributed through-out the immensity of the realm. At the same time, one can easily become lost in a minute detail. Seemingly at odds with each other, the dynamics of the big and the small modes of perception are not decoupled; rather, they interact continuously, the knowledge of the whole influencing the interaction with the particular, the smallest perturbation sending ripples through-out the whole. Periodically, this coupling leads to closed orbits.

As he gazed at the pitcher plant, Poison Pie became trapped in such a loop. The entirety of Faerie was peering over his shoulder as he pondered what to do with this insignificant cup of fluid. He felt as if a microscope now magnified each gesture and thought, displaying them for all of the world to critique. At the crux of this issue lay his decision with the cup. Should he drink it? Should he instead offer it to one of the others? Should he pour it out on the moist forest floor as an offering to the forest gods? Although one part of him understood the utter insignificance of his choice and the inevitability that whatever his decision, it would soon be forgotten, another part of him could not release the fear that his actions would become an irreversible element of the history of Faerie. He succumbed to a paralysis of the body, in which all of Faerie stood still, frozen in time, waiting for him to respond.

Poison Pie closed his eyes. Although time remained still, the instant thus frozen was changing. An invisible entity, casting only a dark shimmer at the silhouette of the figure, appeared in the clearing. Although there were no obvious indicators why this should be the case, it was clear to Poison Pie that he was witnessing an event that happened long ago.

The silhouette approached and, though it was of shorter, more slender shape than Poison Pie, took up the same space. The pink marble heart now occupied both of their overlapping bodies. It formed a nexus spanning individuals and time.

Ordinarily, not knowing what to do pleased Poison Pie immensely. Once that thought occurred to him, he began to breathe again. This world, Faerie, laid no more claim to him than did Earth.

He looked again at the cup. It was inexplicably empty. Time had jumped discontinuously ahead. Poison Pie’s choice had been made, though neither he nor the rest of the universe, was any the wiser as to what it might have been. It dawned on Poison Pie that there were avenues of escape from seemingly impossible situations, avenues that defied all comprehension. He suspected that he had just witnessed such a moment, or came as close to witnessing it as can be done of such a moment that has been erased from existence, or perhaps more appropriately never existed.

Poison Pie looked to Tchict’Ict and the faeries. They seemed unaware of any unusual phenomenon. They showed not a whit of interest in him or his empty pitcher. He momentarily doubted that he was present at all.

“I’m still here,” he called out.

To this unprovoked, existential cry, Celia raised an eyebrow, while Princess Pie raised her star lantern to bathe Poison Pie in a celestial glow, which caused the tattooed runes to dance on his skin.

Tchict’Ict stepped over into the light, his mandibles inches from Poison Pie’s face. “That first night I met you,” said the insect man with uncharacteristic solemnity, “when we camped on the road, I had a vision that prompted me to abandon my companions and join your quest. I could not possibly have known then that you would lead me through the City that Crawls, past the inspection of a Mechanical Sentience to this enchanted forest.”

Poison Pie wanted to explain that he too hadn’t seen any of this coming, but he held his tongue.

“I anticipate now,” said the insect man, “that there will come a moment when you lead where we cannot follow. Thus, when you tell me, ‘I’m still here,’ it serves only as a warning of what is to come, of a time when you abandon us.”

Poison Pie again wanted to protest, wanted to vocalize the words, “That isn’t what I intended to say,” but, catching himself, he thought better of it. It wasn’t clear what he had intended to say and he decided that allowing the ambiguity to remain provided the easiest, if not safest, path forward.

|

|

|

|

|

June 4, 2014

Tchict’Ict removed the book from Celia’s pack and lay it on the stump, where Princess Pie hovered, inspecting it. “You lost the key?” she asked Celia.

“It was given to me without the key,” Celia replied, examining the runes on the cover, illuminated by the star lantern.

“Then you need a locksmith,” Princess Pie concluded.

“That’s exactly what I was thinking.” Her reply surprised Tchict’Ict and Poison Pie for whom a locksmith had been the last person on their minds.

“I know a great locksmith,” Princess Pie announced delightedly.

“Oh, happy day!” Celia replied, admittedly getting caught up in her role as a faerie.

“But he’s in prison,” Princess Pie added.

“I see,” said Celia, trying to keep the disappointment from her voice.

“It happens to all the good locksmiths. Eventually, they open a lock they shouldn’t have opened.” Princess Pie hovered, humming excitedly. “I’ve never been part of a jailbreak before.” Had her wings been absent, her sheer ebullience at the prospect would have kept her aloft.

Poison Pie tried his best to ignore the conversation. He knew very well the purpose of the book, namely to unravel the riddle of the letter written on his flesh. Since he had no desire that such a riddle should be answered, he hoped his role in the jailbreak would be pivotal, thus when he withheld his aid, the plan would collapse.

The faeries meanwhile continued to discuss the book.

“What’s in the book that’s so important?” Princess Pie asked.

“It will allow me to translate these runes.” Celia gestured toward the characters on the book’s cover.

“They are on your mushroom man too,” pointed out Princess Pie.

“So they are,” Celia agreed.

“You know what he’s got on him, don’t you?” Princess Pie asked.

“No,” Celia slowly replied, as Poison Pie looked toward them with an undisguised expression of alarm on his face. “I don’t. Do you?”

Oblivious to the subtle exchanges between the other three members of the party, Princess Pie continued, “Well, I can’t exactly read these runes, but from its aura the nature of the story is clear to me. It’s an old story. It has a name, you know.” She looked around, pleased to find a rapt audience. “The story is called, ‘The One Who Came Before’.”

Breaking the silence that followed, Celia asked, “How does it go?”

“There are countless variations on the story. Like any proper story, each time it’s told it’s different.”

“What’s the general theme?” Celia asked again.

“It’s about the one who came before and, naturally, the one who comes after.”

Princess Pie quickly lost interest in the flurry of questions that followed. The momentary anxiety that had gripped Poison Pie quickly passed as it became clear that to make any particular sense of the letter, they would still need to break a locksmith out of prison. The title itself, ‘The One Who Came Before’, disturbed Poison Pie not in the least, for all creatures are positioned in a temporal sequence located between their ancestors and their descendants. He could easily pretend there was no illumination to be gained from his knowledge of the title.

|

|

|

|

|

June 9, 2014

Ignortus, like all goblins, suffered from the reputation of his species as an obnoxious, obsequious and generally objectionable breed. The root cause of the lack of civility in goblin-kind can be traced to physiological adaptations in the limbic system of their brains as well as to a reduction of the role of the amygdala in the control of emotional response. Those scholars of the body who have chosen the task of studying the various species of goblinoids hypothesize that the evolutionary path taken by this branch of the family tree emphasized both mechanical proficiency as well as magical resiliency. The aspects of magic and technological adaptability are rarely observed in a single species or society, because in order to be maintained they both require substantial resources, be they intellectual resources of the brain or economic resources of the kingdom. To embrace both technology and magic, something must be sacrificed. In goblins, the brain sacrificed not only civility but a host of other abstract emotional constructs, including nobility, humility, dignity, generosity, and any other trait remotely associated with altruism.

In exchange, Ignortus and other goblins demonstrated an uncommon knack for both magic and mechanics. Locksmithing was only one example of trades, in which the combination of disciplines was valued. Ignortus created locks (and other clockwork mechanisms) imbued with a supernatural invulnerability to damage, or possessed of an unnaturally pernicious response when tampered with. The administrators of his particular Goblin Town put his talents to good use in the manufacture of unbreakable safes for the stolen goods or bribes they had accumulated. Also in demand were trapped door mechanisms of all kinds, leading to secret chambers in which all manner of goblin skullduggery was concealed. These same leaders exercised the poor judgment typical of goblins in failing to adequately compensate Ignortus for his services. Consequently, Ignortus expanded his business market by offering his locksmithing skills to a nearby community of giants.

The dominant mutations in the physiology of the brains of giants are not as well understood as those of goblins for two reasons. First, acquiring specimens is more difficult in the case of giants who exist in fewer numbers and are naturally endowed with a superior ability to defend themselves, owing largely to their ferocious size. Second, even when one is able to acquire a giant’s brain, the organ is exceedingly difficult to analyze owing to the fact that the brain of a giant is so tiny. Nevertheless, much about giant behavior is known simply from careful observation of their activities, best performed from a safe distance. The most important rule of giant society is an old rule, namely, “Might makes right.” The biggest, strongest giant always gets what he wants until another giant can take it from him. Thus, once the value of Ignortus’ services were recognized within the giant community, they did not approach the administrators of Goblin Town in order to negotiate for his time. Rather, a horde of giants burst through the town defenses, shattering wood and scattering stone, until they located the locksmith, at which point they stuffed him and a haphazard selection of the tools of his trade in a course burlap sack and carried him back to their lair.

Imprisoned in the cell of a dungeon, secured by an iron gate, which Ignortus, had he the mind to, could have picked in a matter of moments, the goblin began a lucrative career in giant locksmithing. The giants repaid Ignortus in appropriately over-sized bundles of gold coin and super-sized portions of mutton leg. So prolific was Ignortus at his trade that soon the cell overflowed with gold, and the giants began to leave their payments along the dank walls of the stone corridor leading up out of the dungeon.

One supposes that, even in Faerie where the passage of time is a nebulous concept, Ignortus eventually would have grown tired with his ceaseless accumulation of more wealth than he could possibly make use of during his lifetime, but, then again, there are examples among other species (humans come to mind) where individuals never recognize a reasonable limit to their personal wealth. Regardless, Ignortus, if he was ever to reach this unlikely realization, had not yet come to it by the time that Poison Pie was recruited to effect his rescue.

|

|

|

|

|

June 9, 2014

When Princess Pie explained to the rest of the group, in her rather whimsical and round-about way, that the locksmith was currently employed by giants, the reaction she elicited lacked enthusiasm.

“What kind of giants?” Poison Pie asked, who knew such creatures came in a variety of distinct breeds, including hill giants, fire giants, frost giants and storm giants. None of them, he suspected, were to be trifled with.

“Faerie giants, of course, the Fomoire” Princess Pie replied, as if nothing could have been more obvious.

Tchict’Ict, who had previously traveled in the company of a half-giant knew of their great propensity for destruction. “Are faerie giants violent?” he asked.

“Whoever heard of giant who wasn’t violent?” Princess Pie replied with a laugh, a carefree response which provided no comfort to either mushroom or insect man.

While the faerie never precisely described their visit to the locksmith in such terms, it became clear that stealth was a key component to the success of the endeavor. “Does your mushroom man know how to tiptoe?” she asked Celia.

“I don’t know,” Celia replied; she couldn’t remember having ever witnessed Poison Pie tiptoeing. She tried to imagine such a thing and it brought a smile to her face. “Can you tiptoe?” she asked the mushroom man.

“I can do one better than that,” Poison Pie promised. “I can become invisible.”

At this declaration, Tchict’Ict turned his attention to the mushroom man, whom he was quite sure could not become invisible.

To his and the other’s measured amazement, Poison Pie sort of sucked in his breath and stood perfectly still and became something that seemed more or less all parts mushroom and no part man and exceedingly uninteresting. It was as close as one could come to invisibility while still remaining completely in plain sight.

Princess Pie approved. “Excellent,” she said. “And, if that doesn’t work, are you a fast runner?”

Poison Pie did not appreciate her lack of confidence, no matter how cheerily it was communicated.

The lair of giants proved to be an immense castle, built by a king of men or of man-sized creatures to proportions that exceeded his physical size but corresponded to his elevated opinion of himself. Unfortunately for that monarch, the giants judged it to be exactly suited to their grand tastes. The change of occupants was over in a matter of hours, much to the detriment of the previous owners. The gradual decay of the castle occurred over a much longer time scale, accelerated only by sporadic displays of temper by the new inhabitants, who would occasionally knock out a wall or shift the foundation of a tower, hastening its eventual collapse. Consequently, the castle now stood in ruins, set off from the forest by a plain stamped clear by the traffic of giants and backed up against a sheer precipice, which fell several hundred feet to a continuation of the forest below.

The balustrade along the top of the outer wall was pocked with giant gaps, in which the stone was scattered on the plain before it. The parapets on the few remaining towers remained out of reach of the giants and were covered in a thick coat of ivy. The gray stone itself, hewn in large, rectangular bricks, cut and lifted from the side of the cliff on which the castle stood, provided the canvas upon which a mosaic of mossy green and brown lichen was now painted. Today it seemed, the sun had chosen to rise above the horizon, though it appeared faint in the mist. In the morning fog collecting in this clearing, the castle presented a forlorn greeting to the travelers.

As they left the cover of forest, the morning song of the birds faded behind them. No creature dared breach the land within the vicinity of the castle. Poison Pie and Tchict’Ict walked side by side; the two faeries fluttered around them, sometimes beside them, sometimes overhead.

“It’s awfully quiet,” Tchict’Ict commented in a quiet voice, though he suspected an ambush to be a tactic not employed by those who typically relied on overwhelming strength.

“As I said, giants are rumored to sleep late,” Princess Pie replied, now adopting a whisper herself in the eerie fog.

The party traveled across the plain undisturbed. The arch of the stone bridge had collapsed, so the two land-bound travelers clambered down into the moat, which held only giant, curiously mismatched footprints in a layer of soft mud, and then scrambled back up the far bank. A bent and rusting portcullis lay on its side, telling clearly of a violent moment in the distant past when it was ripped from its moorings. The outer courtyard held a variety of detritus—mounds of crumbled stone, animal skeletons, a circular fountain with the bottom half of a white marble statue of a mounted hippocampus, surrounded now by a stinking pool of septic filth.

Crossing the courtyard, the cautious travelers veered to a smaller entrance to the left, thinking that the largest, central entrance led to the throne room where the giants presumably slumbered. The smaller hallways still showcased twenty-foot ceilings, but the party hoped these ancillary corridors would lead to a staircase, descending into the depths of the castle, where presumably prisoners were kept.

Once they descended into the dungeons, their initial fears that they would have to wander through a labyrinth of passageways was found to be misplaced, for there was a clear path, lined in sacks and buckets of gold coins and trunks of silver plates and cups leading to the cell in which Ignortus slept. A more obvious route could not have been imagined, even if large signs bearing the message, “Goblin this way” and an arrow pointing down the hallway, had been posted.

Stone walls formed Ignortus’ cell on three sides, with the fourth closed with iron grating. The gaps between the iron bars were sufficiently spaced to allow a faerie to slip through, which Princess Pie did, though very carefully since iron is toxic to faeries. Celia followed suit, leaving Poison Pie and Tchict’Ict to nervously wait among the piles of gold in a corridor that was still clearly large enough for giants to traverse.

Without warning Princess Pie whispered a word that caused her star lantern to flare brightly, momentarily blinding her companions and instantly rousing the goblin from his sleep. Dressed in ragged, striped pajamas, he jumped to his feet, standing all of three and a half feet. His paunch hung out from his pajama top and his warty, scabrous head was covered by a matching cap. To outsiders the faces of goblins seem perpetually distorted by obscene sneers and that of Ignortus was no exception to his uninvited visitors. He scrutinized his company, trying to make sense of the odd assemblage of faeries, mushroom and insect. His greeting matched his rough appearance, “Who are you and what do you want?” he barked in a voice that was uncomfortably loud.

To her credit, Princess Pie maintained her composure and replied, as cool as could be, “We have heard of your unequaled skill as a locksmith, O Master Ignortus, and have come to engage your services.” She appended a good bit of additional flattery, which seemed rather comically obvious and heavy-handed to Poison Pie, who did not understand that one could not be too fawning in goblin society.

This flattery soothed the goblin’s startled nerves, as it became apparent to him that not only did his visitors present a business opportunity but they understood the nature of bargaining with goblins, a fact to his advantage since it would not be necessary for him to explain to them the insatiable nature of goblin greed (as if the piles of treasure accumulating dust both inside and outside his cell were not explanation enough). He moved tersely to business, since the morning was getting on and he too understood that his landlords would not appreciate the presence of other customers, no matter how well moneyed they were.

“I don’t come cheap,” Ignortus warned them, as he wandered over to a dirty corner of the cell and unceremoniously proceeded to relieve himself in a chamber pot.

Once finished, he tersely brushed his hands together then strode over to his work bench, swung the chair around so that it faced the visitors then plopped down in it. His curiosity at the unusual composition of the group and the fact that they were willing to brave the threat of giants to see him was duly roused. “What have you got for me?”

The faeries glanced over to Tchict’Ict on the far side of the iron grating, who produced the book of runes from Celia’s backpack.

Ignortus strode to the edge of the cell and peered intently at the book. He spoke to himself in an unpleasant goblin voice, as if no one else was listening. “A magic book. And an old magic. Such a book will have a powerful spell upon the lock. Very interesting. Give it to me.”

With a quickness his portly frame belied, he thrust a dirty hand through the bars and snatched the book from Tchict’Ict who had been holding it out for his inspection.

Ignortus cooed in an even less pleasant tone, “I can feel the magic in this book.” He glanced over at Poison Pie. “It’s the same magic that’s settled on that thing.”

“We’ve lost the key,” Celia called from behind the goblin.

“Of course, you don’t have the key,” Ignortus snapped. “I’m not an idiot.”

“Can you open it” Celia asked, maintaining a level tone.

“Of course, I can open it,” Ignortus replied, unable to contain his pleasure at the challenge. “The only question is whether you can afford my services. How will you pay me?”

“We can rescue you from this dungeon,” said Poison Pie, hoping to contribute something useful to the conversation and no longer be thought of as “that thing” by the locksmith.

Ignortus cast an incredulous look at the mushroom man, “Are you not only a moron but blind to boot, you filthy fungus? Why in the name of Faerie would I want to be rescued?” He waved his hand at the piles of gold spilling out onto the floor as if no other words were necessary.

Poison Pie frowned. He had no reservations against touching iron. He grabbed the iron door and tore the old metal from its hinges. Setting it down as quietly as possible, he stepped through the opening and approached the astonished locksmith, who had underestimated the capabilities of the mushroom man but who understood very well the threat of violence. “There’s no need for this,” he cried in a high-pitched squeal.

Poison Pie slowly raised a massive mitt.

“If you damage my fingers or my eyes, I won’t be able to do the work,” the goblin pleaded.

Poison Pie brought his fist down on the goblins head, which possesses a notoriously thick skull, with sufficient force to knock the creature out. While Princess Pie muttered something about not letting her negotiations run their course, Poison Pie emptied a sack of gold, stuffed the unconscious goblin inside, handed the book of runes back to Tchict’Ict and grabbed a black leather satchel filled with tools from the work bench. In an unintentional recreation of the goblin’s arrival to the cell, Poison Pie slung the sackful of goblin over one shoulder and gripped the satchel in the crook of his other arm, for the handle was too small for him to work his mitt through.

As quietly as possible, Poison Pie navigated his way back out of the dungeon, past the cesspool in the courtyard, across the foggy plain and into the cover of the forest. When they felt they had put a safe distance between themselves and the castle, the party stopped.

The locksmith was beginning to come to his senses when Poison Pie dumped him out of the sack onto the forest floor, where the negotiations reconvened in the following manner.

“How will you pay me for my services?” demanded the goblin, propped up on his elbows between the roots of a great oak.

“We know of a delightful cell,” Poison Pie replied, “where you can work at your craft to your heart’s content and be paid in so much gold it will spill out of the cell and down the hallway. If you open this book for us, I promise to take you there.”

The goblin contemplated the offer. In truth it seemed quite reasonable to him. Had their places been reversed, and he had possessed the strength of his abductor, he would likely have acted in a similar manner. What surprised him only was that the mushroom, whose reputation relied on more subtle methods of manipulation, had resorted so quickly and so effectively to violence. “Fine,” snapped Ignortus. “I’ll do it. But you have to take me back as soon as I am done. Swear on it.”

Poison Pie nodded; forgetting that in Faerie oaths, no matter how casually taken, cannot be broken without dire consequence. He was bound now to return the goblin to the giants, who upon discovering the absence of their locksmith would not so easily lower their guard a second time.

If one wonders, as Ignortus had, at the somewhat surprising proclivity for violence exhibited by Poison Pie in this particular endeavor, one must remember that Poison Pie was older than he seemed. He had previous, unpleasant experiences dealing with those who had no appreciation for the subtleties of virtue, who in fact viewed all virtue only as weakness to be exploited for their own advantage. After some time and consultation with various authorities on the subject, Poison Pie had adopted two maxims on the topic of dealing with such people. First, one should avoid difficult people as much as possible. Second, when one was able to avoid them, one should always retain one’s own dignity and never stoop to their level.

Poison Pie’s obvious failure to adhere to these principles represented only another manifestation of his inability to live up to his expectations for himself in the lifelong process, which others before us have euphemistically labeled chronically poor decision making.

|

|

|

|

|

June 13, 2014

“The origin of locks lies in the privatization of property,” said the goblin. “Locking books of course protects intellectual property.”

Poison Pie yawned. The better part of a day had passed, while Ignortus infrequently tinkered with the tools in his satchel but mostly just stared at the book. Poison Pie had had no idea that locksmiths were so boring. Tchict’Ict had lost interest over an hour ago. He was somewhere up in the heights of the trees, where he had discovered a hive full of honey. Although the bees buzzed furiously around him, their stings could not penetrate his chitinous exoskeleton.

“The crucial question in this case,” Ignortus droned on, “is whether this book is locked to protect the information from your eyes or...” The goblin glanced up at the two hovering faeries. Princess Pie was weaving her hands in such a manner that glimmering star dust miraculously fell out of the space between air molecules. Celia imitated the gestures as precisely as she was able but without any visible result. The goblin raised his voice and repeated, “Is this lock meant to protect the information from you or, rather, to protect you from the information contained within the book?”

Summoned by the raised voice, Tchict’Ict dropped from the tree. Discovering no progress had been made in opening the book, with an impressive leap, he disappeared back into the leaves. With a similar lack of response, the faeries continued their chatter.

The goblin turned to the mushroom man, seated only a few feet away and asked in a tone of mixed disgust and envy, “How is it that your party has survived this long paying so little attention to the obvious warning signs along the way?”

Poison Pie, of course, knew the answer to this question, knew that warning signs were as often as not misleading, tempting one to choose another, potentially safer path, although there was no guarantee of the rightness of this choice and there was the heavy likelihood that by opting for self-preservation one forsook opportunities of another quite possibly more rewarding kind. “Perhaps we have survived this long precisely because we have ignored the warning signs.”

Ignortus snorted at this reply. “Only a mushroom would say that.” It was not meant as a compliment, though Poison Pie took it as one all the same.

Few locks can withstand the practiced and patient persistence of a goblin locksmith. Aided both by an intuitive understanding of the mechanical clockwork and no less by a natural magical agency, Ignortus eventually opened the lock with a pop! Surprisingly both pieces of the lock detached from the front and back covers of the book, leaving no sign that it had ever been sealed.

“I like this lock,” said the goblin, pocketing both halves of the mechanism.

Celia said nothing; it seemed a small payment for his services. She flew to hover over the goblin, looking at him expectantly.

“I’m not opening it!” he said with obvious surprise. “In fact, I would ask that you not open it until I am safely back in my cell and you are far away. A lock like this isn’t put on just any old book.”

Celia frowned. She had waited for some time to open the book; a little longer wouldn’t make much difference, or so she surmised. Tchict’Ict took the book from Ignortus and deposited it back in the pack.

“Now take me back,” said the goblin to Poison Pie.

“Right now?” said Poison Pie. It was the middle of the night, or seemed to be based on the irregular cycle present in Faerie.

“The sooner the better.”

They set off. Along the way, Poison Pie understood that their past travels would have gone a lot slower if Ignortus had been in the company; the stride of the waddling gait of the goblin was much shorter than that of the others. Moreover, the goblin would not consent to be carried in any manner, until they reached the edge of the clearing surrounding the dilapidated castle. At that point, he climbed back in the sack and had Poison Pie haul him over his back, telling the others, “We have to make this abduction look convincing.”

“Well,” Celia asked, “what are you going to tell the giants when they want to know why we brought you back?”

“Some version of the truth,” the goblin promised. “Anything else is too dangerous in Faerie.” The goblin spoke truly. Just like most other places, the truth will out and the outing in Faerie can be particularly explosive.

It was more or less morning when they left the forest. It again seemed the most likely chance for returning the goblin undetected, though all them thought it quite possible the giants would have stationed a guard so soon after the theft of their locksmith. This suspicion caused them each no small anxiety, save Princess Pie who appeared to have a natural immunity to anxiety of any sort.

Halfway between the castle and the forest edge, Poison Pie asked over his shoulder, “Can we leave you here? Is this close enough?”

“No,” insisted the goblin from within the sack. “You swore an oath. I need to get all the way back in the cell. If they see me strolling into the castle on my own, they’ll be prone to make a jelly out of me.”

So, Poison Pie continued with the two faeries buzzing quietly behind him and Tchict’Ict as silent as an assassin taking up the rear.

They entered the courtyard, which was as lifeless as it had been during their first visit. No birds sang. No rats scurried across the surface. The same stink of sewage filled the air.

Tchict’Ict strode up beside Poison Pie and whispered, “I sense a trap.”

Before Poison Pie could reply, the voice from inside the sack whispered back, “So what? This mushroom doesn’t heed warning signs.”

Thus, there seemed little alternative but for Poison Pie to lead his party through the courtyard, down through the same side corridors to the stairwell leading down into the dungeon. At the gold-lined entrance to the cell, Poison Pie quickly set down the sack, from which the Goblin virtually leapt back into the cell.

“Now let’s get out of here,” Tchict’Ict chittered. Although the unpleasant odor of giant permeated the castle, it seemed stronger than before. Each moment, he expected an attacker to leap from the shadows at one end of the corridor, or worse yet, both.

Celia too felt a palpable sense of danger. “I think he’s right. Let’s go.”

“You haven’t fixed my door,” Ignortus pointed out.

“That wasn’t part of the deal,” Tchict’Ict replied, looking to Poison Pie for confirmation.

“That’s my protection against the giants,” Ignortus replied, knowing full well that a giant could destroy the door just as easily as Poison Pie. “Seeing me back in my cage will convince them all is right again.”

Over Tchict’Ict’s protests, Poison Pie nodded and lifted up the bent iron door. He had seriously damaged the hinges when he yanked it from its place. He leaned it sort of precariously against the opening in the cell.

It would take almost half an hour, during which Celia and Tchict’Ict nervously scanned the corridor, for Ignortus to straighten the hinges of the pins and reattach the door, while Poison Pie held it in place. When the work was done, Ignortus stuck a hand through the bars and with a flick and jab of a slender tool, locked himself back inside.

During that time, the giants, who had been hiding in ambush, waiting for their valuable locksmith to be returned safely before launching an attack on the offending kidnappers, regardless of how repentant they might be, grew impatient. They decided instead to seal the three castles entrances to the dungeon with large boulders and wait until later in the day to deal with the intruders. The giants first dragged stones to two entrances that were sufficiently far away that the sounds of their labor were not apparent to the party, whose ears were filled with Ignortus’s exclamations of contempt for the lackluster skills of his assistant in door repair. However, when the giants placed the last stone over the entrance leading to the treasure-lined hallway, the massive stone fell with a crash that reverberated through-out the dungeon.

There was no question among the five individuals gathered on either side of the cell what the sound meant.

“That way is sealed,” said the insect man, who wondered now if it were sealed from the outside or the inside. However, no giants appeared down that path, so Tchict’Ict cautiously scouted it back to the entrance, where he discovered the several ton stone slab blocking their escape. He reported as much to the rest of the group, who received the news with stolidity.

When Ignortus explained that there were two other exits from the dungeon into the castle, they had little hope that the giants would have left those open. With directions from the goblin, who refused to leave his now sealed cell, they conducted a tense exploration through the dungeon, which confirmed that indeed all three staircases leading to the surface were sealed.

“What do you think is going to happen?” Princess Pie asked as they gathered back in front of the goblin’s cell.

“Either the giants will forget about you until they need me again, which could be weeks,” said the goblin in an off-hand manner, “or when day comes, they rise and, as a group, hunt you down in these dungeons, which they know very well.” The goblin peered at the group through the iron bars. He admired the door. “You did a bang up job on my door, after all,” he said to Poison Pie, as if goblins uttering niceties under dire circumstances were the most natural thing in the world.

“The stairs continue further down,” said Tchict’Ict. “What’s down there?” He thought only of potential tactical advantages in the event that the giants did enter the dungeons to retrieve them.

The goblin explained that there were several levels of dungeons in which the stone walls and floor were hewn smooth. These levels contained empty cells and store-rooms filled with whatever goods the men who had built the castle left behind, though many of the rooms had been looted by the giants. Below that, there were entrances to a natural cave system that led further into the Earth, eventually leading down to a large cavern. As far as the goblin knew, there weren’t any exits down there. At least nothing came up from the depths.

“We might be able to elude the giants down there.”

“Forget it,” said the goblin. “The giants know that cavern well. It’s their garden.”

“They are gardening giants?” asked Poison Pie, skeptically. “What do they grow, giant turnips?”

For a moment, Ignortus assumed Poison Pie was joking or intentionally being obtuse, but as the mushroom man never changed his expression, Ignortus realized there was no limits to the Poison Pie’s ignorance and told him so. “You are the most ignorant mushroom man I have ever met.”

“Why’s that?” Poison Pie said, without really being offended, for he had a steadfast belief that knowledge was by and large over-rated. “Is it supposed to be common knowledge what giants grow in Faerie gardens?”

“Of course,” said the goblin.

Poison Pie looked at his companions on his side of the iron bars. “Well, if it was so obvious, I think one of us would know.”

“She knows,” said the goblin pointing to Princess Pie.

“Of course, I know,” said the faerie. “Everyone knows about the Fomoire.” She looked at Poison Pie. “Except him, I guess.”

Tchict’Ict stood quietly in the background, giving no indication that he too was complicit in Poison Pie’s inexcusable ignorance. Celia too kept quiet, though later she would insist that it was only to faithfully maintain her role as a faerie.

“Well, what is it?” Poison Pie said, exasperated.

“Mushroom men,” said Princess Pie.

“Faerie giants grow mushroom men?” Poison Pie mistakenly thought that restating the claim would make the ridiculousness of such a statement clear to everyone.

“Faerie giants created mushroom men,” Ignortus clarified.

“I find that highly unlikely,” said Poison Pie, “and somewhat offensive.”

Although neither Ignortus nor Princess Pie were able to provide Poison Pie with a satisfactory creation myth, they both insisted that it was common knowledge in Faerie that giants were the party responsible for breeding sentience into mushrooms.

“But I told you,” Princess Pie added. “They are not like you. They are much more mushroomy than you.”

“Are they tough?” Poison Pie asked.

Princess Pie glanced at Ignortus and both nodded in agreement. “They can be pretty tough.”

“Then I’ve got an idea,” said Poison Pie. “I will go down to the garden and marshal up an army of mushroom men. Then we’ll just take out the giants with a swift strike from the vanguard of boletus and then we’ll trap their main force in pincer maneuver between the truffle brigade on the right flank and the mounted morel cavalry on the left. Then, singing the victorious chanties of the fungal kingdom, we’ll march right out the front gate.” Poison Pie dusted his two mitts together as if executing his plan would be no more difficult than having conceived of it. For his part, Poison Pie thought it was very unfair that the four assembled around him considered these words to be the most preposterous thing that any of them had heard for quite some time.

|

|

|

|

|

June 16, 2014

The star lantern of Princess Pie guided their steps through the darkness of the dungeons. They passed the landings to two deeper levels, stopping only for a brief inspection, in which they could perceive that some effort had been made to level the floors and smooth the walls. As the stairs led further down, even those elements of architecture gave way to the natural contours of the stone, defined not by men but by age-old geological processes. The stairwell deposited them at the head of tunnel that descended sometimes gently, where they were able to walk, albeit along a meandering path, around stalagmites and columns, and sometimes abruptly, where Poison Pie and Tchict’Ict resorted to scrambling on all fours (or all sixes as the case may be) over rough rock to descend to the next plateau. In no place did they have to squeeze through small openings for there remained numerous signs along the way that these paths had long ago been broadened to allow the passage of giants.

Princess Pie warned them that the deep places of Faerie were no safer than those on Earth, but reassured them that, at a few hundred feet below the surface, they passed still through the shallows. All the same, Tchict’Ict proceeded on high alert, sensors adjusted to maximum sensitivity, expecting an attack from each shadowed cranny. Poison Pie, on the contrary, sensed no danger; the regular traffic of giants had marked these caves as off-limits to any predators with a reasonable likelihood of visiting the shallows. The leviathans of the deeps that could swallow giants whole did not venture here.

“It feels different,” said Celia, as she waited at a corner for Poison Pie and Tchict’Ict to catch up to the faeries, whose progress was unimpeded by the terrain, “than when we traveled to the City that Crawls.”

“Yeah,” Poison Pie agreed, panting when he finally arrived, “No Proteus Olm.” He made no attempt to hide the relief in his voice. Poison Pie did not, on principle, like to think poorly of the dead, even when they deserved it, so he mentally added a quick thought hoping that Olm had found some semblance of peace after death. For the record, it should be noted that Poison Pie did not consider this mental locution a prayer, as he staunchly believed that he did not pray. All other misgivings aside, the mushroom god, the Deadly Galerina, was proving very difficult to locate; Poison Pie was under no illusion that his prayers would have an easy time finding him. Regardless, their native guide through the dark places of Faerie was a marked improvement over Olm, despite her continuing assumption that Poison Pie and Tchict’Ict were somehow Celia’s pets, or servants at the very best.

The caves were cool and moist. The growing humidity revealed that they neared water as they continued their descent. Soon, the source of the moisture became apparent as they emerged from the cave into a sprawling cavern, the ceiling struck with a thousand stalactites, overhanging a lake, which stretched into the darkness, beyond the light of the star lantern. Had the party been able to observe the entirety of the lake, they would have beheld a body that resembled in shape, nothing so much as a kidney. The margin of exposed stone around the edge of the lake was bordered on the far edge by the rising stone walls of the cavern.

From their vantage point at the cave opening, situated atop a pile of rocks perhaps thirty feet above the water’s surface, Poison Pie and his companions were in a position to note that every square inch of available stone, from the water’s edge to the cavern wall, was occupied by enormous mushrooms, with groups of two foot-tall specimens clustered around the edges of gargantuan mushrooms that reached nine feet at the tip of their caps, and all sizes in between.

The party observed the garden for several minutes, during which time it became clear that a movement among the throng was occurring on a much longer timescale than it would have had it been a crowd of mammals below them. These were clearly the mushroom people that Princess Pie and Ignortus had described as more mushroom-like than Poison Pie. In truth, they seemed ninety-nine parts mushrooms; but this mistaken impression of the proportions of their heritage was based on the fact that Poison Pie relied exclusively on a visual inspection. Their stems separated just barely, if at all, to form two legs; otherwise they shuffled across the floor like an ungainly woman wearing a tight, floor-length gown. The mushrooms possessed arms, but when the arms were not active, they lay flat against the stem, almost impossible to detect. Virtually hidden beneath the caps, these mushroom people possessed faces bearing eyes, nose and mouths that were only modestly differentiated from the surface of the stem. While the stems ranged from ochre to olive to grays and near black, the caps themselves—some tall and pointed, others round and broad—possessed as much beauty and variation as butterfly wings, displaying colorful patterns, some obeying radial symmetry and others more amorphous in design. Dry caps curled with white, papery flakes. Slimy caps glistened with a purplish, translucent ooze. Bioluminescent markers illuminated no few caps. Lacy frills adorned the edges of some caps, where others were smooth and a few caps bore what most resembled a thicket of barbed wire around their perimeter.

The diversity and splendor of the scene beneath them struck each of the visitors. Poison Pie for his part felt somewhat intimidated, due to his own rather mundane appearance.

Celia flew to hover over his shoulder. “It’s a magnificent garden, Poison Pie.”

The mushroom man looked up at her and shrugged; he could take no credit for it. He sensed no more kinship with these creatures than a human might for a mouse in the company of reptiles. Poison Pie wondered what role the giants played in cultivating such a remarkable garden. Did they take an active role in promoting this growth or did they simply reap a natural resource when the harvest came due?

“It’s quite valuable,” Princess Pie added. “Each mushroom produces spores and fluids from which powerful unguents, magical and medical, can be prepared. This garden is worth more than if the entire cavern were filled with veins of gold.”

“They’re strangely quiet,” Tchict’Ict remarked. Now that it was brought to their attention, each of the visitors noticed that the only sound in the cavern was the barely perceptible rustle of a periodic scrape of a foot (such as it was) over the wet stone. “It’s unusual for so large a crowd to maintain such silence.”

“Well, they’re telepathic,” Princess Pie said by way of explanation.

“It seems,” Celia said, bringing everyone’s attention back to their current predicament, “that we could hide in here for quite some time, avoiding detection.” None of them particularly relished the idea of lying low among the mushrooms until sufficient time passed that the giants lowered their guard, allowing a better chance of escape.

Poison Pie needed no further invitation. He decided to test the supposedly telepathy of the cavern’s inhabitants. He composed himself and projected a mental message out to the mushroom people. It went something like this: “I am Poison Pie, Man of the Mushroom People, Champion of the Deadly Galerina, Deus Fungus.” It was immediately clear to all present that an abrupt change swept over the crowd of mushrooms, as all motion however slight ceased, though only Poison Pie understood what had triggered it. Just a moment before Poison Pie intended to add a request for information regarding an alternative exit from the cavern, every mushroom synchronously released a cloud of spores that billowed forth from their caps and exploded in the air like an impossibly dense array of fireworks, creating suddenly an impenetrable fog that filled the cavern. No matter how quickly, Celia and Princess Pie attempted to pull the top of their shifts over their mouth and nose, they were already exposed to the particulates in the cloud. Tchict’Ict who did not wear clothes, initially held his breath, though eventually he too exposed his lungs to the spores. Poison Pie, however, breathed deeply for he sensed that this fog represented, among other things, an unfettered pathway to an exchange of information.

The combination of spores served several purposes. The most quickly acting agent induced an emotional response, generating an empathy for the mushroom people and diminishing any aggressive thoughts. The second compound in the spores opened the mind of the visitors to the telepathic communication (or rather bombardment for there were so many voices in the crowd) of the mushroom people. Instantly, the clamor of the crowd, the absence of which only minutes before Tchict’Ict had noted, now filled their minds if not their ears. A third compound slowed their thoughts, rendering their decisions sluggish, slowing their movements to a timescale more on par with that of the mushroom people and, if necessary, more easily countered. Another compound introduced a trigger, as of yet unactivated, that would induce paralysis in the host at the release of an additional spore, held now with bated breath within each of the mushroom people. There were other compounds in the spore fog as well, whose purpose eluded Poison Pie.

There was no longer any need for Poison Pie to explain his circumstances. The mushroom entity—for though they had separate bodies, it was not such a great stretch to describe their communal thoughts as a single organism—experienced Poison Pie’s state of mind. Curiously, the sensation seemed not so much an invasion, as when the Mechanical Sentience had scoured their memories. Instead, it seemed that sharing his thoughts with the mushroom people was as easy as falling into a hole. Gravity did all the work; Poison Pie was simply an object participating in a trajectory governed by forces beyond his control if not comprehension.

It’s difficult to render this mental exchange of information in conventional dialogue, but owing to the constraints of the medium, we now attempt to do so.

Mushroom Throng: Champion of the Deadly Galerina, why have you made us wait so long?

Poison Pie: I don’t have any idea what you are talking/thinking about.

Mushroom Throng: We’ve been down in this hole a long time.

Poison Pie: You don’t like it here? You seem to be doing so well. Everything is so lovely. Is it the giants? Are the giants hurting/hunting you?

Mushroom Throng: No, no we love the Fomoire, especially the chief gardener, the Tuinman. He’s kind, in his own way, though he guards us with a violent jealousy that cannot entirely be described as originating from a concern for our best interests. It’s just that we had no idea when the one that came before said another would follow that so many ages would pass between. We had almost lost hope.

At this last admission, the mushroom people communicated a palpable wave of emotion, which almost knocked Poison Pie to the edge of an irreparable hopelessness. He immediately succumbed to the desire to do anything in his power to lessen this sense of despair.

Poison Pie: Well, I am here now. How do we get out?

Mushroom Throng: We shall show you the way. We are ready to meet the Deadly Galerina.

A path appeared as the mushroom crowd parted like the Red Sea before Moses. Poison Pie led Tchict’Ict and the faeries, down the sloping pile of rocks and into the midst of the mushroom people. As the party moved forward, the path closed behind them. They were guided, as if in a trance, around the edge of the lake, to a crack in stone wall, hidden in shadow. Poison Pie stepped into the crack and after winding through the narrow crevice for several minutes emerged in the cloudy light of Faerie.

Before him lay the same great forest of Faerie they had left only hours before. Above and behind him climbed the rock wall, at the top of which, three hundred feet above, stood the rear wall of the giants’ ruined castle. Poison Pie craned his neck up admiring the view until Tchict’Ict nudged him from behind, pushing him aside so that he, Celia and Princess Pie too could observe that they had returned to the surface of Faerie.

The mushroom people issued one at a time from the crack in the rock. The crowd began to grow around Poison Pie. He stepped away from the sheer cliff into the forest beside it, hoping to give the mushrooms space. However, the crowd continued to grow. It dawned on him that perhaps all of the mushrooms were taking this opportunity, which had it seemed always been present, to leave the garden. Poison Pie was forced to continue backing away, as each additional mushroom emerged from the cliff wall. Soon, he was pushed so far back that the foliage of the forest obscured his view of the cliff.

Princess Pie, at his side, chose this moment to express her opinion on the matter. “When the giants discover what you’ve done, they are going to be so pissed off.”

Poison Pie nodded. “We should leave.”

“As quickly as possible,” Tchict’Ict agreed.

One of the spores released by the mushroom people acted as the needle of a compass, directing Poison Pie to the fungal pole where resided the Deadly Galerina. Thus, when Celia asked Poison Pie which way they would go, she was surprised by the uncharacteristic lack of hesitation and the confident pace of his stride.

Any hope of eluding pursuit by the giants was lost when the travelers noticed that the passage of several thousand mushroom people trailing faithfully behind Poison Pie left a swath of destruction through the forest in which all fauna in the undergrowth was trampled to a torn green mat under a river of shuffling fungal feet.

Poison Pie understood that his metaphor as Moses continued, for he now led on a holy pilgrimage his people to a land promised them long ago. Like Moses, he had the benefit of a burning bush of sorts—the ever-present voice of thousands in his mind—that had laid out the rules and compelled him to move forward. Also like Moses, he harbored serious doubts as to his own worth in assuming the leadership role. At any rate, he hoped the journey didn’t take forty years to complete. His devotion to the Deadly Galerina was not quite so exemplary as the prophets of old.

|

|

|

|

|

June 18, 2014

As they marched through the forest, Poison Pie asked the Mushroom Throng, “Is it true that the giants of Faerie created the mushroom people?”

The Mushroom Throng replied: In understanding the answer to this question, it helps to have an understanding of the giants of Faerie themselves. We perceive that you have never directly encountered a faerie giant, or a Fomoire, as they are known here. Therefore, some preliminary description is appropriate. We begin with a digression, which may initially seem irrelevant, but will lead us to the answer to your question.

Over the course of time, nature, through an accepted evolutionary process, has created various species, in which each individual of a given species shares a majority of common characteristics but also is uniquely differentiated through genetic mutations that are a key element of long-term survival. Inevitably, evolution is a cruel process because there is no intelligence guiding it. Rather, it relies on brute trial and error to modify a species so that they are more suited to survive in a changing environment. For every million adaptations, only a few are advantageous. The rest, more often than not, constitute a miserable variety of dead-ends. Worse yet, once a particular modification of the genetic code is found to be debilitating to the organism, there is no governing intelligence to learn from that mistake. Instead, the mistake is repeated again and again. The futility of evolution is surpassed only by its success at maintaining life, a success due strictly to obstinate perseverance rather than, say, cleverness.

On Earth, people accept this futility because they have no other recourse. Such is not the case in Faerie, where magic pervades the soil, atmosphere and waters. In Faerie, dead-end mutations, which would otherwise limit the ability of the organism to operate efficiently, are compensated for by magical means.

The giants of Earth, more than most creatures dwelling there, perhaps owing to their prodigious size, suffered at the hands of the whims of genetic mutations. When a giant was born with one leg substantially shorter than the other, the fall was all the greater. Giants possessed two traits, which aided them greatly in responding to this injustice. First, they got angry—angry at the immutable natural order of the world. Second, they chose to act; if the world of Earth would not change to accommodate them, then they would find another more pliant world.

Eventually, a band of giants, ancestors of the Fomoire, collectively exhibiting the most gruesome collection of birth defects, arrived in Faerie. In Faerie, they discovered that legs of different length allowed the individual to move in ways that foes could not anticipate. A shriveled arm, too weak to wield a club, could strike instead with a twig that shattered stone. Eyes of different sizes, placed in unusual positions and at conflicting angles around the face, allowed sight not only in the physical world but in incorporeal domains as well. Polydactylism led to supernatural dexterity, while oligodactylism made one impervious to all means of scrying at a distance—a useful trait when one wished not to be found. The descendants of these original giants came to be known as the Fomoire. They are, not surprisingly, an unpleasant lot to look upon.

The Fomoire prefer to dwell in isolated places, often underground, where they can be left to their own devices. In one such location they discovered subterranean mushrooms and, in them, found a companionship utterly free of repugnance at their physical appearance. That an amity between mushrooms and these particular giants should arise is not all that unexpected since mushrooms themselves are notoriously unsightly, associated with molds and slimes that are synonymous with filth and decay.

In the combined silence and darkness of one fungal-infested cave, the first Tuinman sought solace in meditation. This giant possessed a stub rather than arms sprouting from each shoulder. The stubs were short and fat and ended with a splayed group of webbed fingers that fairly resembled a mushroom cap. The mechanism by which the magic was performed cannot be explicitly articulated with paper and ink, but the result was undeniable. The Fomoire had begun their work at waking the mushrooms.

The giants had grown accustomed to silence and granted the mushrooms the ability to communicate without voices, so that the stillness of the cavern air was not disturbed. The ability to move was also imparted, though the giants chose not to bestow graceful strides, but rather a constrained shuffling, which brought to mind the erratic gait of giants on uneven legs. Despite the various adaptations, the Fomoire preserved the appearance of the mushrooms, simultaneously capable of evoking both wonder and disgust.

In return, the mushroom people provided the Fomoire with treasures unobtainable outside the fungal kingdom—powerful psychedelic agents, which acted as a means of communicating with divinities; compounds capable of instant paralysis for which no known antidote existed; and unguents of healing, able to enact virtually any medical procedure short of bringing the dead back to life. The worlds would be a much better place if all creations repaid their creators so handsomely.

When the Mushroom Throng had finished answering his question, Poison Pie, raised a skeptical eyebrow. “Even though you make it sound sort of reasonable, I don’t think that’s how it really happened,” he replied aloud.

Mushroom Throng: Do you have an alternative explanation?

Poison Pie: I’m working on it, as we speak.

|

|

|

|

|

June 20, 2014

Celia darted along, maintaining irregular orbits about Poison Pie, as he led the horde of mushroom men through the enchanted forest of Faerie. Several times, Princess Pie, also circling the leader of the march, narrowly avoided mid-air collisions with Celia.

“Watch where you’re going!” Princess Pie ordered in a high-pitched, imperious tone.

“I’m getting tired,” Celia admitted, so Poison Pie drove the horde to a halt, turning to stare in what most clearly resembled disbelief at the size (or perhaps even the existence) of the crowd behind him.

“Itchy,” called Princess Pie, “get out Celia’s book. I’ve been dying to take a look in it since Ignortus unlocked it.”

The insect man obediently removed the book of runes from Celia’s pack slung over his shoulder. He casually lifted the front cover (contrary to Ignortus’ fear, there was no explosive trap released upon opening) and displayed it in his upper arms, open to the first page, where the two faeries hovered and examined the text.

Poison Pie stoically ignored the entire proceedings. He decided instead to make a tour of his troops; perhaps by the presence of his leadership, he would boost morale, or something along the lines of what a proper general ought to do for his army—for indeed, Poison Pie felt absurdly like a general.

The title page of the book, written in a dozen languages, at least one of which was known to both Celia and Princess Pie, was mostly easy to read, “A Book of Runes. Translations to Twelve Common Tongues. Edited by Rune 1. Commissioned by Rune 2.” The names of the editor and commissioner were not translated themselves, but rendered in symbolic runes.

“Do you know these names?” Princess Pie asked.

Celia shook her head. “The second rune looks familiar.” The only place she could have likely seen such a rune was tattooed on the flesh of Poison Pie, who she now observed was shrinking in the distance into the midst of the mushroom people.

“Turn the page,” Princess Pie commanded, to which Tchict’Ict passively acceded.

The two faeries read through the book, discovering that the challenge before them was more difficult than either had anticipated. The runes did not represent a phonetic alphabet or any system of compact syllabary. Rather, it gradually became apparent that many of the ornate symbols were composed of smaller parts that represented physical objects, abstract notions, or perhaps pronunciation in a tongue no longer spoken in any known land. Within the book were many tens of thousands of symbols. Despite the editor’s insistence on the logical organization of the book, it nevertheless became clear that the translation of the runes that appeared on Poison Pie would require a time-consuming, side-by-side process, in which each individual rune on Poison Pie was located within the book.

“Too much work,” Princess Pie concluded. “I’m going to go find the most colorful mushrooms.” With that adieu she flew off over the crowd.

“What do you think, Itchy? Is it worth the effort?” Celia quietly asked the insect man.

“Did you just call me Itchy?” Tchict’Ict asked, his antennae twitching.

“You haven’t corrected Princess Pie,” Celia said, keeping her eyes focused on the book, but allowing a sly smile to escape. “I thought you might like it.”

Tchict’Ict had never had a nickname before. His kind did not use nicknames as expressions of affection, which was itself a rather foreign concept to insects, for whom the idea most closely related to affection was an acknowledgment of familiarity. He stifled the instinctive response to request that Celia immediately cease using the nickname and address him by his proper name, or at least her best pronunciation of it. Instead, he allowed his mind to wander, wondering if in Faerie there was a magic woven between individuals through such terms of endearment. Because the object of his study utterly exceeded his knowledge of it, he could not formulate a proper response and was consequently rendered silent.

Tchict’Ict returned to Celia’s earlier question. “We have come this far with Poison Pie. It seems reasonable that the runes he bears contain some important information that will aid us in our pursuit of the original owner of the pink marble heart. Therefore, we should decipher the runes.”

So, when Poison Pie returned from his inspection, they made him stand still as a mushroom, while Celia studied him from every angle, like an artist absorbing the contours and shadows of the subject of a painting. Tchict’Ict patiently followed, holding the book open. Even Princess Pie eventually joined in, shining the star lantern into Poison Pie’s ears and nostrils (where no additional runes were found). It took several hours of the evening to confirm that scrawled across Poison Pie’s forehead were the worlds, “The One Who Came Before”.

“I told you so,” said Princess Pie. “I recognized that much just from the feel of it all.”

Celia also discovered something else that first night. On the bottom of each heel of Poison Pie’s splayed feet was the same rune that was used as the name of the commissioner on the title page of the book. Had Poison Pie ever admitted to them that he had eaten the letter accompanying the pink marble heart, they would have been able to deduce that the commissioner of the book was the signatory on the letter. Since Poison Pie had opted to keep this information to himself, they made no such connection.

“You are following in the footsteps of the one who came before,” Celia surmised.

“I suppose so,” Poison Pie admitted grumpily, for, though he cooperated in the process of translation, he did so under protest, maintaining his resolute opposition to having the tattoos translated.

The two faeries consulted over the proper pronunciation of that character. When they had come to an agreement, they announced it to Poison Pie. “Gorgonio.”

“Of course,” Poison Pie said with a grimace, “Who else could it have been?”

|

|

|

|

|

June 23, 2014

The Mushroom Throng sent Poison Pie a message, which he related to the others. “They said we should increase our pace.”

Tchict’Ict turned his attention to the shambling multitude that followed them through the forest. He had been under the impression that they were responsible for setting the slow pace.

“Did they tell you why?” Celia asked, already guessing the reason.

“The giants are following us,” Princess Pie replied, to which Poison Pie only nodded in confirmation. He chose not to share the additional information communicated to him by the Mushroom Throng that, in addition to their prodigious size, the giants of Faerie were expert warriors. A single giant would prove more than a match for Poison Pie, a bug and a pair of faeries. To worsen matters, the report indicated that several giants drew near.

It fell to Tchict’Ict to ask the question that Poison Pie himself had been silently harboring. “Do you think we will find safety in the presence of the Deadly Galerina, if we do in fact reach it?”

Poison Pie shrugged. “That does seem to be the over-riding presumption.”

There was no counter-argument against hurrying, so hurry they did, guided by a navigational surety endowed by the spores of the mushroom people. The enchanted forest, while undeniably possessed of an otherworldly beauty, proved unable to waylay them with detours into shadowed vales, holding ambiguous promises of sylvan calm or joy or pleasure. In fact, when, in their haste, they inadvertently entered a stretch of the forest in which a particularly predacious flowering vine emitted a tranquil aroma in order to lull trespassers into a sleep from which they would never wake, the party passed without incident. The mushrooms for their part seemed impervious to such lures. The four companions marching at the head of the crowd, now with the threat of giants at their heels, rather easily shook off the temptation to succumb to the narcotic lethargy, and continued their progress without pause. Only Princess Pie recognized the uncommonly good fortune in their passing unscathed; their wills were certainly steeled by that of the Mushroom Throng. She did not share this observation with her companions since it would only have served to reveal her lack of vigilance in failing to alert them to the dangers of Faerie, which should have been obvious to a native such as herself.

With such efforts and a fair bit of luck, Poison Pie and his multitude out-paced the giants, reaching their destination without encountering their pursuers. To say that Poison Pie and his company were disappointed when they discovered the Deadly Galerina, while certainly true, does not properly convey the gamut of emotions experienced upon their arrival. Ten minutes prior, the land had begun to gently rise to a ridge and the forest gradually had thinned. By the time they reached the crest, the trees had almost entirely given way to an undergrowth of ferns and broad-leafed shrubs that reached knee-high on Poison Pie. The sun of Faerie, no longer impeded by the forest canopy, revealed itself veiled and somber in an overcast sky. From this ridge, Poison Pie observed that in fact he stood on the lip of a crater, several miles in circumference, completely surrounded by the enchanted forest beyond the ridge, and lush with green vegetation but completely devoid of all trees within.

The Deadly Galerina lay face down in the valley of the crater, with one foot propped up on the slope, almost reaching the encircling forest and its arms stretched out over its head leading down into the depths of the vale. Had the Deadly Galerina been standing, it would have spanned about nine hundred feet from the base of its feet to the top of its head. There would be no standing for this gargantuan figure now. As the mushroom people managed their way up the ridge and formed a growing crowd around Poison Pie, all clearly observed this god was dead and had been so for quite some time by the looks of it. There was no electric aura of power in the air, nor psychic weight indicating the proximity to a greater entity. Poison Pie experienced nothing but the awe of something once living so immense and a disappointment that it could not have waited to die until it had finished conducting its business with Poison Pie.

Celia’s eyes too ran over the length of the Deadly Galerina. It had been human-shaped, or at least had assumed a human shape for the act of dying. It had two legs, two arms, and a head attached at positions appropriate to a human to its enormous torso. The skin was swarthy and leathery, like that of Poison Pie, only older, tougher, more dead and free of tattoos. The carcass, including the scalp, was bare of all hair. Celia tore her attention from the corpse to assess Poison Pie’s reaction; his visage remained inscrutable to the monk.

The other faerie fluttered about the ridge. “You know,” Princess Pie began, addressing herself to Celia, “based on what you had told me...” She paused, pirouetting in mid-air as her eyes followed the Deadly Galerina from finger tips to toes, before continuing, “I thought you were taking me to see a living god.” None of the three saw fit to correct Princess Pie of this misconception.

Tchict’Ict, ever the pragmatist, noted only that their hope of sanctuary from the giants by the good graces of the Deadly Galerina had been sorely misplaced. This valley, from a strategic point of view, was a death trap.

The mushroom people for their part flooded over the ridge and down into the valley, heading straight toward the Deadly Galerina. When they reached the body, they found gentle slopes, particularly along the fingers where they could climb onto the cadaver. Once atop the body, they distributed themselves until the entire body was covered in a fine growth of over-sized mushroom people. The entire procession took about half an hour, during which time Poison Pie and his companions watched from the point on the ridge where they had first gained sight of the valley and its contents. Their immobility was partly due to a suspicion that the mushroom people were performing some ceremony with a significance that they could not grasp. That Poison Pie, despite his mycological heritage, was excluded from participating in this ceremony, was not surprising nor alarming to him; his was a life in which he had never belonged.

I am tempted to write that the Mushroom Throng began to sing, but we equate singing to a vibration of pressure waves in the air. Their song was rather carried only through a cascade of spores ejected from every individual on its perch above the dead god in a choreographed sequence of puffs and bellows. The song, regardless of the form, was unmistakably a lament. A god had died. Those who despise divinity would likely have chosen to rejoice. The mushroom people had no reason to despise the Deadly Galerina, who had never promised them immortality and thus could not be held accountable when such a gift was not forthcoming. Consequently, the dirge of the mushroom people for the Deadly Galerina provided simply an opportunity for the community to raise their voices together and, as a whole, marvel at the beauty which they could only collectively create.

All on the ridge were moved by the display, though not one of them understood its meaning, other than accepting that the living who remain mark the passing of other living creatures, though they are bound only by the shared experience of life.

“What now?” Celia asked Poison Pie as the song of the mushroom people lowered to a hum.

“We go inside.” Poison Pie led them along the rim of the crater until they reached the sole of the foot near the ridge. There, Poison Pie found an opening in the otherwise intact black skin of the corpse. He turned sideways to slip inside and found that the corpse was hollow. The skin itself had apparently calcified over the ages, providing it with a surprising structural strength that allowed it to withstand the weight of thousands of mushrooms atop it. Or, rather, perhaps the magic of Faerie had contributed to an enduring monument of a divinity who chose to expire within its borders.

The skin, however strong, was not opaque. A yellow, translucent light managed to penetrate the shell. Where the mushroom people stood above them, darker brown circles appeared on the interior surface. Upon the ground a dense but soft mossy fur covered the soil. The song of the mushroom people, thought diminished, reverberated softly, finding resonance within this anatomical structure. Poison Pie stepped forward, allowing Tchict’Ict, Celia and Princess Pie to enter behind him.

They stood as a group dwarfed in a chamber the shape of foot, with a hallway leading from the ankle up into the leg. The Deadly Galerina had stood one-hundred fifty times taller than a six-foot-tall man and all proportions roughly obeyed this ratio. Where a man might have an ankle three or four inches in diameter, the ankle passageway of the Deadly Galerina reached fifty feet.

Poison Pie led them through the ankle and down the right leg. He had no guidance to select a particular destination, but the fact remained that he had a second pink marble heart within him, which had driven this quest thus far; it seemed not unreasonable therefore to make for the spot where the heart of the Deadly Galerina would have lain.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This work is made available to the public, free of charge and on an anonymous basis. However, copyright remains with the author. Reproduction and distribution without the publisher's consent is prohibited. Links to the work should be made to the main page of the novel.

|

|

|

|

|

|