|

|

|

|

The Poison Pie Publishing House presents:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

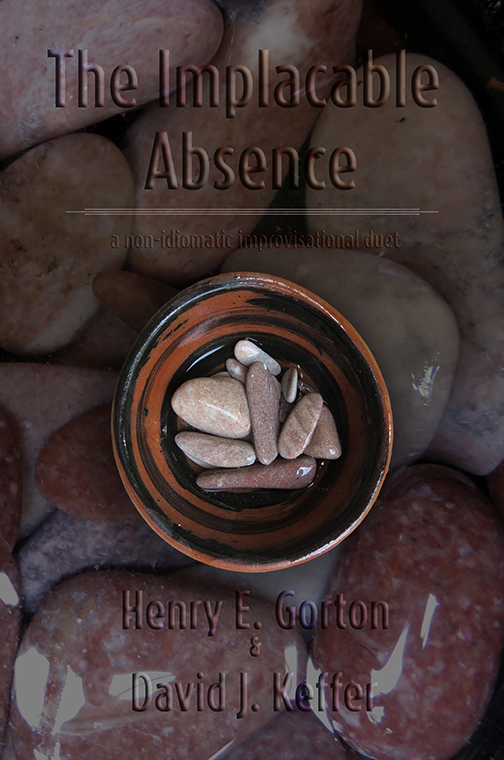

The Implacable Absence

A Non-Idiomatic Improvisational Duet

Henry E. Gorton & David J. Keffer

(link to main page of novel)

July

|

|

|

|

|

July 3, 2014

Giants have their own gods, fashioned in roughly their own image. In the case of the Fomoire, in which the otherwise dead-ends in evolutionary mutations were given new life, the gods were a miasmatic agglomeration of mismatched parts filled with an equally incoherent collection of thoughts. That such gods saw fit to visit the Tuinman with a dream of his own death, in which he was devoured by voracious fire ants, could neither be taken too literally nor entirely ignored.

The Tuinman shook off the dream and limped on his uneven legs over to the five giants who had accompanied him in pursuit of the stolen Mushroom Throng. Their distorted forms were each splayed out on the mat of vegetation rendered flat by the passing of thousands of shuffling mushroom feet.

Curiosity more than vengeance drove the Tuinman. That the strangers who had kidnapped their locksmith and inexplicably returned him a day later should prove able to make off with the entire garden was unfathomable to him. No one had yet exhibited a stronger connection to the Mushroom Throng than had he, otherwise they would have rightly been appointed Tuinman. Some small portion of this current Tuinman harbored the misgiving that he was actually in pursuit of his replacement. This thought added a degree of reluctance to his erratic stride.

|

|

|

|

|

July 3, 2014

Seated on a blanket of moss at the point where the heart should have been located within the enormous corpse of the Deadly Galerina, Celia hovered over the book of runes, while Poison Pie paced back and forth.

“I think this next rune means shadow,” she said to herself as much as to any of the other three. She read the runes off Poison Pie’s abdomen with this interpretation. “His shadow does not follow him.” Celia shifted her eyes to the book then back to Poison Pie. “Suck your gut in,” she ordered. “I can’t tell if the rune for the verb is ‘to follow’ or ‘to obey’. She recited the sentence with this alternate translation, “His shadow does not obey him.”

“Who’s shadow?” Princess Pie asked.

“Gorgonio,” replied the monk with a confidence she did not feel, then admitted her uncertainty by adding, “I suppose.”

“What does it mean for his shadow not to obey him?” asked the faerie.

Celia had been asking herself the same question as she gradually arrived at the translation. “Shadows have no mind of their own. Their movements are completely determined by the movements of the body exposed to the light source. Perhaps,” Celia answered, “it means that Gorgonio found a way to escape the laws that govern light.”

Princess Pie found this to be a very unremarkable attribute. Her kind had long ago learned to capture the light of stars and nurture it within their lanterns. She felt quite confident in her belief that the star lantern was a much more glorious manifestation of defying the laws of optical physics than a mere disobedient shadow. On this occasion, she chose to keep her thoughts to herself.

Celia remained deep in thought. Sporadically, a mushroom person shifted on the shell of the divine corpse above them, causing a rippling effect through its kin, which created a muted but nonetheless bewildering strobe-like effect within the corpse. Eventually, Celia announced, “There could be another interpretation. It could be,” she said, “that Poison Pie, keeper of the marble heart, is the shadow of Gorgonio, following in his footsteps.”

“But I thought you just said that the shadow did not follow the one who came before,” Princess Pie said.

Celia fixed Poison Pie with an appraising stare. Poison Pie meekly obliged in returning her gaze. “Perhaps,” said the monk to the man of the mushroom people, “your destiny is not written in stone. Perhaps, you will be presented with the opportunity to deviate from the path set before you.”

For his part, Poison Pie was delighted with the multiple interpretations of the runes. He wanted nothing nailed down, least of all his future. “Maybe,” he suggested, hoping to further muddy the waters, “The marble stone once cast a shadow on Gorgonio whilst he was sun-bathing, leaving a pale birthmark on his forehead in sharp contrast to the rest of his well-tanned complexion. When the sun set and moon came up, it misunderstood this pale spot to be a badge of allegiance to the moon. It ordered Gorgonio to lead the legendary Lunar Brigade, a command, which, for reasons he would not confess, he could not obey.”

While his attempts at obfuscation were transparent to Celia, Princess Pie proved both less familiar with Poison Pie’s devotion to ambiguity and more gullible to flights of fancy in general, and began her own extrapolation of the story thus begun based on her limited knowledge of the grand exploits of the Lunar Brigade.

All of this chatter was as meaningless to Tchict’Ict as if it had been spoken in a foreign tongue. Crouched with his back to the others, he kept eye on the cavernous tunnel leading down the right leg of the Deadly Galerina, by which they had arrived. His first indication that something was amiss proceeded from a change in pitch to the inaudible but nevertheless perceptible (on some level) hum of the Mushroom Throng. Tchict’Ict thought only of two possible triggers for this change in activity. Either the mushroom people were accelerating the rate of their decomposition of the corpse of the Deadly Galerina or they were acknowledging the arrival of something new in the valley.

The pitch steadily rose until everyone inside the corpse became aware of it. Celia stopped translating the runes and Poison Pie stopped pacing. Tchict’Ict closed the book and put it in the backpack, which he handed to Poison Pie. “Maybe we should go,” he said to the others.

“Where do we go to?” Poison Pie asked. There were only a few choices, the left leg, the arms and the neck. Perhaps there was another exit from one of those appendages. None of those options seemed particularly inviting and they remained standing where the heart should have been.

They heard the ungainly gait of the giants before they saw them emerge from the dappled darkness of the right leg of the Deadly Galerina. Six in number, they were led by one who used a gardening hoe as a cane. These six giants of Faerie resembled each other only in their size, standing well over ten feet, and the wealth of their afflictions. The particular nature of the deformities varied markedly from one individual to the next. The leader, the Tuinman, as identified in the intensifying song of the Mushroom Throng, suffered from a malady of the skin that made him appear as if he were covered in moist, freshly tilled soil. One eye was thrice the size it should have been and the other half that. The nose was placed crookedly and the mouth obscenely wide. He distributed his great weight from one shriveled leg on the hoe, clasped in a massive hand at the end of a burly arm. The other arm lay slack against his side. Hair sprouted in ragged tuffs roughly appropriate to the places one finds hair on other mammals. The Tuinman, though well-loved by mushroom people, presented a most hideous aspect to those unaccustomed to the Fomoire.

The passive reactions among our heroes hinted only at their own detachment from civilized society. Poison Pie, having lived as an outcast at least in part due to his own admittedly much less shocking physical features, felt a degree of sympathy for the giants. Celia, even before her monastic training, had understood the superficiality of external appearances; though such a philosophy ran in direct contradiction to the belief of doppelgängers who in general held that the form in which they appeared presented the whole of the truth, at least for the time being. Tchict’Ict, exile of the insect world, in which pale, segmented grubs were cherished as the future of the species, possessed no inherent biases regarding the appearance of mammals, though he did accept that the assemblage of so many debilitating mutations represented a slap in the face in the good order of natural selection. Princess Pie, lastly, having observed from safe distances the Fomoire many times in the past, was unmoved. As a group, they waited. The Mushroom Throng had already warned them of the formidable skill of giants in combat. The party knew the danger of even one such fighter, much less half a dozen.

The Tuinman, for his part, scrutinized the party, looking for threats—two faeries, mischievous but cowardly and ultimately harmless, a bug, and a man, tattooed from head to toe in holy runes, in whom the work of mushrooms had taken hold. Surely this last was the one who had led the Mushroom Throng from the Tuinman’s garden; he posed the threat. The Tuinman shook his hoe at the Mushroom Man and bellowed a wordless challenge.

Poison Pie frowned and shrank back. The Mushroom Throng acted as a conduit through which everyone within the corpse, giant or otherwise, perceived a general understanding of the others. Poison Pie understood that the leader of the giants had come to reclaim the Mushroom Throng, by force if necessary.

Poison Pie thought an explanation in order. He began, “I didn’t really ask them to come along, you know. They just wanted to see the Deadly Galerina. Admittedly, we all thought it would still be alive. Finding it dead has really put a crimp in all of our plans. Perhaps, having seen that the Deadly Galerina is dead, the mushroom people will return with you to the garden.” Poison Pie ended on a hopeful note, then added belatedly. “I for my part have no further use of them.”

Born of a race prone to anger, the Tuinman ignored his misgivings, roared and sprang forward with an agility completely inconsistent with the appearance of its limbs. Poison Pie had not known that the magic of Faerie worked to compensate for the inadequacies of the deformed bodies. Thus he was totally unprepared for the graceful, leaping pirouette of the giant, which culminated with the blunt end of the hoe slamming into Poison Pie’s chest, knocking him twenty feet backward to roll across the mossy blanket, coming to rest in a collapsed heap.

The Tuinman, now again a creature of mismatched proportions, slowly hobbled over to Poison Pie’s still form. It had all been written in ages long past. The events spilled forth in exactly the sequence foretold by the one who had come before. The Tuinman raised the hoe to deliver the killing blow in accordance with the ancient prophecy.

His blow fell not on the flesh of Poison Pie, but was deflected by the crescent blade of a pole-arm wielded by the bug, who had managed to cross the substantial distance between them in the blink of an eye.

The Mushroom Throng vibrated the antennae of Tchict’Ict with a sorrowful song, filled with the futility of his actions. He would earn only his own death, shortly followed by that of Poison Pie. He would die defending Poison Pie, just as Sariputra had forewarned on the mountaintop, only his death would be in vain.

There are certain advantages to life in the insect world. One particularly relevant advantage is that futility has no meaning in a life governed entirely by biological roles. From the moment of one’s conception, one’s role is pre-defined. What mammals call ‘fate’ or, even worse, ‘doom’ is a concept rendered meaningless by the insect’s utter acceptance of a life dedicated to fulfilling a single purpose.

Thus the song of the Mushroom Throng had little effect on Tchict’Ict. Instead he focused on survival. He began a most intricate and lethal dance with the Tuinman. Seemingly defying gravity, their bodies became an air-borne whirr of iron weapons mounted on wooden poles. The dexterity of the Tuinman, as well as his ability to perceive the movements of his foe at all angles, whether fixed by his odd eyes or not, presented an impenetrable defense. Tchict’Ict at one moment perched on a single leg atop the giant’s head, then a moment later wove around his legs, looking for a vulnerability, jabbing with bladed shields and crescent’s edge.

Some authors demonstrate a great skill for particularly detailed descriptions of combat. Such is not the case for the authors of this tale, as may be evident by now. Rather, they possess a distaste for violence, which limits their willingness to explore it in depth. It cannot be denied that this exchange of blows had to occur in order for the story to move forward, but we neither sensationalize the violence nor advocate it as a means of resolving disputes. Somewhat ironically, both combatants shared this philosophy. Tchict’Ict fought only to preserve the life of one of those in his adopted clan. The Tuinman fought only because he was afflicted with a lack of imagination that did not permit him to consider a path beyond that which had been laid out for him long ago. In truth, this Tuinman and all those before him, who shared much of the placidity of mushrooms, were in large part gentle souls, misfits among a violent race.

Once begun, the outcome of the battle was not to be denied. One combatant would die within the corpse of the Deadly Galerina. One can suggest that Tchict’Ict emerged the victor, plunging a blade deep into the neck of the Tuinman, primarily because the giant had no previous exposure to any species remotely related to Tchict’Ict. The ignorance of the Tuinman caused him to underestimate the abilities of his foe. Tchict’Ict felt not an iota of pride at the defeat of his foe; such celebration in death, beyond the acceptance of nourishment, is not to be found in the insect world.

When the Tuinman lay dead in a pool of dark red blood slowly spreading over the green moss, Tchict’Ict immediately turned his attention to the remaining five giants. Exhausted, he had no chance of defeating even one of them, much less the group. It occurred to him that he might yet fall beside the Tuinman.

However, the five giants did not attack. Instead, they began a collective howl of grievous lamentation for their Tuinman was dead. Above them, the Mushroom Throng, aghast at the unexpected turn of events, joined in the dirge. The sobbing, low frequencies of the giants and the undulating, high frequencies of the Mushroom Throng resonated within the chamber of the corpse of the Deadly Galerina. Thus summoned, the magic of Faerie began its work.

Princess Pie turned to Celia and found tears streaming down her cheeks. Before she could ask Celia why she was crying, Princess Pie discovered that she too wept. Poison Pie, though his eyes were closed and his broken ribs ached, knew from the response of the Mushroom Throng of the events that had transpired. A pale liquid leaked from between his closed eyelids. Tchict’Ict, bereft of tear ducts, honored his fallen foe with bowed head.

The ghost of the Tuinman, a shimmering, translucent spirit, climbed out of the giant’s body and with a ghostly hoe, drew a vertical line in the fabric of Faerie. He pulled first one side apart, as if a drape, which held itself in place, and then the other, revealing a darkness behind.

Poison Pie painfully rose to a stand and observed the ghost of the Tuinman turn now with his back to the disruption in the continuity of space in order to fix Poison Pie with a forlorn countenance. The ghost produced an unmistakable gesture, waving with his good arm, for Poison Pie to accompany him into the rift.

The Mushroom Throng added a new verse to their song. Poison Pie then understood, though he did not want to, that the Deadly Galerina had entered the World of the Dead and, if Poison Pie were to continue his quest, he must follow.

Without further ceremony, the ghost of the Tuinman stepped into the blackness of the rift and disappeared from sight. With an apologetic glance at Celia and Tchict’Ict, Poison Pie reluctantly followed.

“Ah,” thought Tchict’Ict, “though I didn’t die today, I still enter the World of the Dead.” He followed Poison Pie.

While the magic still lasted, Celia turned to Princess Pie and bid her farewell. “I leave behind a friend in Faerie.” She briefly clasped Princess Pie’s hands in her own. Celia was startled to find in her hands not the warmth of blood but the cold of starlight. Releasing the faerie, Celia fluttered through the rift.

Alone in the corpse of the Deadly Galerina with five wailing giants and four thousand mushroom people, Princess Pie considered her options. She was a skald of the Seelie Court. It was her duty to roam Faerie and observe the great variety of curiosities transpiring within. Once armed with a store of tales, both entertaining and informative, her task was to return to the Court and share her stories. Princess Pie felt certain the exploits that she had observed thus far would be of great interest to court. Her uncertainty lay only in whether the lords and ladies of the Court would be satisfied with the partial tale to which she had thus far been exposed or whether they would deem it a dereliction of duty that she had not accompanied the party unto the completion of their journey.

As such thoughts filled her mind, Princess Pie watched the five remaining giants approach the Tuinman’s body. They recited the words of the Procession of the Dead, and lifted the body in their arms. Slowly, bearing their funereal burden, they marched toward the opening that led down the right leg and out of the Deadly Galerina. The Mushroom Throng, with the decomposition of the Deadly Galerina incomplete, made no move to follow.

The rift began to flicker. It would remain only a moment longer. Princess Pie was frozen with indecision.

What ultimately tipped the scales was Princess Pie’s premonition that not Poison Pie nor Celia nor Celia’s amazing fighting bug would emerge from the World of the Dead to tell their tale. Thus, their story would be lost. It was true that the faceless librarians might rescue the book of runes before it was destroyed and they might even salvage the tattooed hide of Poison Pie for the information it contained, but the story of the fate of the Poison Pie and the insect-man and the monk would have no interest to them. If that story was to be known, it fell to Princess Pie. In that moment, she darted into the rift, before it vanished from existence.

|

|

|

|

|

5. The World of the Dead

|

|

|

July 3, 2014

In philosophy, religion, mythology, and fiction, the afterlife (also referred to as life after death or the Hereafter) is the concept of a realm, or the realm itself (whether physical or transcendental), in which an essential part of an individual's identity or consciousness continues to exist after the death of the body in the individual's lifetime. According to various ideas of the afterlife, the essential aspect of the individual that lives on after death may be some partial element, or the entire soul, of an individual, which carries with it and confers personal identity. Belief in an afterlife, which may be naturalistic or supernatural, is in contrast to the belief in oblivion after death.

In some popular views, this continued existence often takes place in a spiritual realm, and in other popular views, the individual may be reborn into this world and begin the life cycle over again, likely with no memory of what they have done in the past. In this latter view, such rebirths and deaths may take place over and over again continuously until the individual gains entry to a spiritual realm or Otherworld. Major views on the afterlife derive from religion, esotericism and metaphysics.

Some belief systems, such as those in the Abrahamic tradition, hold that the dead go to a specific plane of existence after death, as determined by a god, gods, or other divine judgment, based on their actions or beliefs during life. In contrast, in systems of reincarnation, such as those in the Dharmic tradition, the nature of the continued existence is determined directly by the actions of the individual in the ended life, rather than through the decision of another being.

—adapted from wikipedia

|

|

|

|

|

July 10, 2014

The luminescent shape of the ghost of the Tuinman was no better proportioned than had been his corporeal form. His disfigured visage registered neither dismay nor delight at the appearance of the World of the Dead; his afterlife was exactly as he had imagined it would be. In many ways it resembled the garden he had so long maintained; the air was thick, dank and close. The moist air clung to his skin at each movement, providing no cooling by convection. The darkness here, too, resembled the subterranean darkness of his garden, though here, rather than a canopy of stalactites, a still, night sky hung overhead. If stars persisted above this sky, they were entirely obscured by clouds so thick they may well have been composed of smoke. As in the garden, the landscape was stone, supporting only boulders and rock formations. As expected, no plant life decorated the desolate grounds of the World of the Dead.

Of course, the most significant difference, as noted by the ghost of the Tuinman, between his garden and the World of the Dead was the absence of the Mushroom Throng. The ghost of the Tuinman turned a complete circle to discover one and only one mushroom man, who frowned by way of apology for presenting so disappointing a sight to the gardener.

The ghost of the Tuinman did not perceive Poison Pie as others, including himself, had previously seen the mushroom man. On the contrary, the ghost of the Tuinman observed a pale pinkish ball of light fighting to illuminate the darkness around it. In a most unnatural manner, the darkness simply would not permit the light to travel in the manner to which it was accustomed. The feeble rays arrived at the eyes of the ghostly gardener in a weakened, pitiful state. It seemed to the ghost of the Tuinman that the ball of light was not perfectly spherical but rather possessed internal structure, which gave it an irregular shape. It was difficult to identify the details of the shape owing to the fact that it was, however diminished, a light source.

Around the pink light a shadowy silhouette now existed. This figure did not match the mortal form of Poison Pie. This figure was taller, far more slender. It possessed distinct fingers and toes. It moved with a grace that Poison Pie had never displayed. There was no way for the ghost of the Tuinman to recognize this figure as Gorgonio, the One Who Came Before, because even the distant ancestors of the gardener had not been born when Gorgonio first traveled the planes and taught the Fomoire the crafts to wake the mushroom folk of Faerie.

Poison Pie, for his part, steadfastly refused to understand the script written on his flesh, so he too, in his ignorance, failed to recognize his predecessor. To compound matters, when Poison Pie finally cast his gaze down and examined the body that seemed to draw such attention from the gardener, he insisted on seeing only the same corporeal form he had always known.

An unusual conversation followed between the ghost of the Tuinman, who believed he spoke to another spirit, though one beyond his recognition, and a Man of the Mushroom People, still alive, though now traveling through the World of the Dead on a quest to discover the meaning of a pink, heart-shaped piece of marble—a quest which a fair portion of Poison Pie wished to remain perpetually unfulfilled.

“Oh,” said the ghost of the Tuinman in a tone of lament, “I have died.”

“I’m sorry about that,” answered Poison Pie, mustering what seemed to be a reasonable expression of condolence. “Were you not ready to die?”

“I was and I wasn’t,” admitted the ghost of the Tuinman, who, admittedly, had lived a very long time. “The suddenness of the dying is, I suppose, what takes some getting used to.” He paused and gazed up at the dark, featureless sky. “And my murderer,” he added, “I was murdered by a bug. I didn’t see that coming.”

Poison Pie thought it a bit unfair to describe the death of the gardener at the hands of Tchict’Ict as murder; after all it had been a fierce combat initiated by the giant. Nevertheless, Poison Pie opted to withhold his objections.

The voice of the ghost of the Tuinman dropped to a whisper. “Soon my brothers will return my body to the garden. There it should be decomposed by the mushrooms I have tended. Only now those mushrooms are all feasting on the corpse of a god. I will offer very humble fare in comparison. Perhaps my body will not merit the fungal decomposition of which I have long dreamt.”

It seemed not at all strange to Poison Pie that one should, upon one’s death, seek a return of one’s body to a form in which it could be reused by the living. He too desired such an eventual fate. Mushrooms were, of course, a preferred mechanism for such a transformation. “Well,” replied Poison Pie, after some thought, “You were the gardener. You are surely covered in spores. Even if the current generation of mushrooms remains in the valley of the fallen god, the spores carried on you will be the source of a new garden, owing its existence entirely to the nutrients extracted from your corpse.”

Poison Pie’s words comforted the ghost of the Tuinman. “You are a kind spirit to say such things. Perhaps you are right.”

Poison Pie again refrained from correcting the ghost; if it wanted to think of Poison Pie as a fellow spirit, who was he to argue?

An indeterminate period of time passed in silence. There was little way to measure time in the World of the Dead. Neither the sky nor the land exhibited any change. The gloom, which prolonged exposure to the cloying air of the World of the Dead ordinarily draws forth from those ill-fated living who find themselves here, plagued neither the ghost of the Tuinman, who was dead, nor Poison Pie, who possessed, though he knew it not, something over which he would be indignant if he knew we described as a guardian angel.

“What should we do?” asked the ghost of the Tuinman.

“I suppose I’m going to make my way to the Deadly Galerina,” answered Poison Pie, though he was willing to alter his plans if the ghost of the Tuinman presented a more appealing option.

“The Deadly Galerina is dead.”

“That’s precisely why we are likely to find it in the World of the Dead.”

“Do you know where, in the World of the Dead, to find the Deadly Galerina?” asked the ghost of Tuinman.

“No,” admitted Poison Pie, not the slightest bit troubled. “I have you to guide me and you have a nose for mushrooms.”

“So I do,” agreed the ghost of Tuinman, pleased to find that he was useful even in death.

We mention, without intention to describe it as virtue or vice, that the thought never crossed Poison Pie’s mind that his companions might have followed him into the World of the Dead, despite the fact that slung over one shoulder was Celia’s backpack. In his defense, in the previous passings from one world to the next, they had arrived as a group. None of them had anticipated that they might find themselves scattered in the World of the Dead. In retrospect, such a circumstance is not surprising at all; when one enters the World of the Dead, usually through dying, one is always alone.

|

|

|

|

|

July 11, 2014

Though Celia fluttered through the rift in the form of a faerie she found herself in the World of the Dead in her natural, featureless form. Her skin shone with a milky silver in the scant light. In the transformation, she had slipped from the shift of narkrïmá, which floated lackadaisically side to side like a sheet of paper to the stone ground, where it came to rest beside her. Celia picked up the fabric carefully, experiencing something akin to nostalgia for a form that she should never have been able to assume. One of the rules that governed the transformation of changelings was the conservation of mass, which owing to the relatively constant density of living beings, corresponded roughly to a conservation of volume. Ordinarily changelings could only assume form of approximately the same size as their native state. Upon their arrival in Faerie, deep in the well, Celia had spotted Princess Pie as she had come to extract the mushroom man. The small, darting form had appealed to Celia and the inherent magic of Faerie had allowed her to assume a form that would have been inaccessible to her on any other plane. It made sense then that in leaving Faerie, Celia was forced to abandon the form.

She stood naked, for Poison Pie had taken her pack while Tchict’Ict battled the giant. Celia scanned the bleak horizon all around her, finding only clouds of smoke and rocky steppes. She saw no sign of either her companions or civilization. Trained as a monk to control her emotions, Celia experienced little shock at finding herself alone.

She closed her eyes and meditated, summoning an inner calm in which she could determine a path forward, unclouded by fear and doubt. She reasoned that she had entered a realm of death, perhaps the World of the Dead, perhaps a plane of another name. There were many lifeless places, barren of plants, bereft of animals. The names of such places mattered little. The faerie giant had been killed. His spirit had opened a rift to something beyond and Celia had followed.

Thinking of the faerie giant, a hapless gardener, killed by the sting of an insect buried beneath its mushroom garden, Celia met with a whimsical thought, to which she acceded. If the magic of Faerie could allow her to assume the form of a diminutive faerie, then perhaps the power of the World of the Dead would allow her to take the shape of the dead. She thought of the ghost of Fomoire, its lachrymose expression as it arose from its corpse, its dolorous steps as it marched into the rift. Celia felt the familiar change come over her.

Although she had no mirror, she looked down at her body, examining the transformation. First, she was indeed one of the Fomoire, for one leg was shriveled below the knee, one hand was a two-fingered pincer, one elbow only opened halfway. Her eyes peered out from opposite sides of her head. She stood no less than ten feet fall. Beyond all these physical changes, she sensed now that she was incorporeal, a luminous spirit, generating a pale blue light that extended but a short distance into the voracious darkness of this world. At her feet, the shift of narkrïmá had fallen through her grasp. It seemed a shame to abandon it, but such thoughts quickly dissipated for such a transformation filled Celia with a strange pleasure. She was a part of this world now; its foreignness diminished. She moved, gingerly at first, expecting the unfamiliar size and shape of the body to take time getting accustomed to, but the insubstantial nature of the being imparted its own grace that more than compensated for any limitations of the form.

It is often noted by those travelers who have had the opportunity to visit foreign lands that travel changes the individual because, in observing the customs of others, one develops a broader perspective that includes a reassessment of the customs of one’s native land, which previously had been taken for granted. The monastery sent every monk out to educate themselves firsthand in this lesson. It requires not such a great stretch of the imagination to concede that a mind can be even more greatly expanded, when a traveler is able to assume the form of other peoples, as had Celia. Whether it be the dog-men of the surface world, troglodytes of the subterranean deeps, subroutines of Nirvana, faeries of Faerie or spirits in the World of the Dead, Celia experienced existence in each form, and with each new experience, became an amalgamation of beings not previously assembled.

It was this unlikely combination of sensations that buoyed Celia’s spirits as she gazed at the unforgiving landscape and pondered how to best find her friends.

|

|

|

|

|

July 11, 2014

Princess Pie benefitted neither from the mental rigors of monastic training nor the well-traveled perspective of Celia. Upon arrival in the World of the Dead, the faerie absorbed the gloom of the place in her first glance and instantly performed an about face in the air, regretting her impulsive decision and intending to immediately depart the same way she had come. She was, needless to say, disappointed to discover the means of a reverse trip did not exist, for there was no rift behind her.

Oppressed by unforgiving stone below and the pitiless gray above, Princess Pie, on the near side of panic, rose in the air, thinking her calls would reach farther from a higher elevation. She shouted first for Celia, repeating the name until her throat grew hoarse. She then called for Poison Pie and finally resorted to shouting the insect’s name, “Itchy! Itchy! Itchy!” Her efforts counted for naught for the viscous air of the World of the Dead sucked the energy from the pressure waves carrying her pleas as surely as if they had been muffled by a pillow.

Princess Pie next thought to flash her star lantern from the heights, reasoning that light might travel better through this medium. She urged the light to burn as brightly as she had ever kept it, then rhythmically moved her hand in front of it, as she slowly spun like the lamp of a miniature suspended lighthouse, warning through the fog of danger in every direction. Princess Pie observed as had the others that the strength of light was greatly diminished in the World of the Dead. She held out little hope that any of her companions, if they were indeed anywhere near her, would have spotted this poor illumination.

What the star lantern did attract was a murder of undead crows, ghastly winged flying spirits, neither avian nor man, neither living nor dead, damned to soar through the smoke-filled firmament without reprieve from the ennui of their half-death. The cacophony of their cawing alerted Princess Pie to their presence.

Dozens of these shadows, each twice or thrice the size of Princess Pie, flapped toward her in a flock that exhibited no sense of cooperation but nonetheless approached with rapidity and clear, malevolent intent.

Princess Pie instinctively dove. The light-sucking forms of the spirits altered their path and pursued. Seen from a distance, one might have imagined the star lantern as a hapless meteor falling to earth trailed by an ominous shadow, far too large to have been cast by the object of its pursuit.

It is unwise for the living to venture into the World of the Dead. They do not belong there and the inhabitants of that land abhor their invasive presence. That Princess Pie should suffer such a dismal end would provide only an unnecessary example to a lesson that many of us already clearly understand. There is no need to hasten our own entry into death; it will come in due time.

However, the demise of Princess Pie was delayed. She was granted a reprieve through good fortune only, nothing more. Her star lantern had been observed and recognized as such by one of her companions. As Princess Pie neared the surface, desperately seeking a rocky niche or some partial refuge from the horde that followed, she instead found the spirit of one whom she initially and mistakenly assumed to be the ghost of the Tuinman.

Spirit and flesh cannot easily interact, but one spirit and another engage each other in a manner similar to but not exactly the same as that arising between the meeting of flesh and flesh. Thus, when Princess Pie hid behind the form of the Fomoire, the ghost of the giant was able to sweep a mighty hand and batter away the first several shadowed crows. The host of black spirits lurched backward and, amidst a clamor of flapping wings and squawking voices, demanded that the ghost surrender their prey. Two crow spirits thought to sneak about opposite sides of the giant and snag the faerie on the sly. Their attempt was thwarted by the unconventional placement of the eyes upon the head of the giant, who was able to follow both their movements simultaneously. The giant swatted away one and pinned the other underfoot.

The crows maintained their chorus of demands but attempted no further subterfuge, restrained primarily by the raspy choking and thrashing of the bird beneath the giant’s foot.

“Away,” shouted the giant in a menacing voice.

“We saw her first,” called the crows. “A morsel though she is, she is all the same our feast.”

“She is not for eating,” bellowed the giant.

To this pronouncement, the crows squawked in derision. Of course, she was for eating.

“She is bound to me,” the giant shouted, shaking a threatening fist at the horde, which jumped back at the gesture, “from another time. I have first claim to her.” The crow at his feet ceased struggling and managed only to whimper.

The nature of the crows’ cries changed from rabid hunger to incensed outrage, as they began to perceive that indeed this most unlikely of meals was to be denied them. A second mad rush of crows was violently fended off by the giant. Princess Pie managed to blind several that drew too close with well-aimed blasts of the star lantern. As a result of their assault, three crows fell to the stone with broken wings, courtesy of the giant’s fist. Moaning and cursing, they hopped about from stone to stone around the giant and the faerie, who eyed them warily. The remaining airborne spirits wailed and cursed most vehemently but the giant, though harried, was unyielding in his refusal to give up the faerie.

Eventually, the giant lifted his foot and the crow thus released slunk back along the rock until it had regathered enough of its senses to struggle on wing back to join the rest of its number. Those crows unable to fly hobbled away on black bird feet until they disappeared in the distant shadows of the land. The other crows hovered overhead for some period of time, while the giant kept a watchful eye on them. Finally, in exasperation, they hurled curses at the giant and threats at the faerie, before returning to an endless, hidden flight in the smoke-filled sky.

In the time it took the murder of crows to depart, Princess Pie had reclaimed her composure. One might have thought that such a nasty brush with death would have instilled a more long-lasting effect in the faerie, but one would have underestimated both her resilience and her impetuosity. Faeries are short on wisdom, especially the variety of wisdom that restrains foolhardiness. In the life of Princess Pie, she had rushed headlong into several encounters that had very nearly resulted in her death. In no time at all, she was prattling on to the ghost of the giant who had rescued her. “Whew, that was close! But not as close as the time I flew into a giant bee hive to steal a quart of the royal honey—it’s magical—that the queen bee keeps close to her nursery, for the exclusive purpose of rearing her crown princess. Now, that was a tight spot!”

|

|

|

|

|

July 21, 2014

Arriving alone did not disturb Tchict’Ict; much of his adult life, prior to meeting the half-dwarf and half-giant, had been spent as a solitary scout, traversing the far borders of the lands around the colony. Finding himself alone again, these instincts took over. He ascended to a weathered, rocky promontory and scanned his new environs. In every direction that Tchict’Ict surveyed, the same apparently uninhabited terrain spread toward a distant horizon under unvarying slate gray skies.

Tchict’Ict’s kind had no thought of the afterlife; the insect-men had never created special names for places where the spirit of an individual might go after the biochemical processes associated with life had left the body and were replaced by a set of different biochemical processes associated with decomposition and death. In his travels, Tchict’Ict had begun to understand that other races, mammalian and reptilian, possessed intricate descriptions of locales for an afterlife, often categorized, curiously enough, by the behavior exhibited by the individual during life. Those that worked for the benefit of the community were deemed good and found themselves, after death, in a place of repose and comfort. Those that worked, alternatively, for their own benefit at the expense of others, were judged evil and consequently allotted a place of torment. These concepts had no application in insect society where all worked for the common purpose of the colony. In the myriad of evolutionary mutations, one that drove an individual insect to place its own survival over that of the colony was rare and, when it did surface, was accompanied by a host of other debilitating genetic anomalies such that it proved a short-lived experiment unable to act upon its impulses.

Regardless, Tchict’Ict could identify that this wasteland, devoid even of plant life, was a place of death, verily a world of death. He would not have been surprised in the least to have been told that some called it the World of the Dead. In the absence of bright lights, loud sounds or any other immediate stimuli, Tchict’Ict opened all of his sensors to maximum receptivity, seeking to capture the faintest whisper or pheromone diffusing through the still air, which might yield a subtle clue as to the location of Poison Pie.

He perched atop this pile of stones for some time; he too found that measuring time here lacked meaning. Despite his highly attuned senses, Tchict’Ict felt nothing. This oblivion, this utter deprivation of the senses, seemed to Tchict’Ict an intimation of death, if not death itself.

After several patient rotations, in which Tchict’Ict surveyed all three-hundred sixty degrees, he refined the resolution of his optical scans and began again, this time more slowly. In the distance, he found only a faint line in the rock, not perfectly straight, but sufficiently linear and of such length as to call attention to itself as potentially artificial. He discovered an additional curiosity, one that would have been of minimal interest under any other circumstances—a far distant rock that presented to the sky a sharp point, a feature unlike that displayed by the dull and rounded rocks that otherwise dotted the landscape of the world of the dead. This point appeared to lie along the line.

Tchict’Ict finished his rotation. Finding nothing more noteworthy, he descended from his vantage point and began a journey of some tens of miles toward the line he had perceived in the distance. As Tchict’Ict walked, a part of his brain innately monitored the expenditure of metabolic energy, as it always did. He noted with curiosity that, in addition to the loss of energy due to the conversion of stored energy to mechanical motion, he was also gradually losing energy to some unknown source. It was as if the landscape itself was a parasite sucking the energy of life from him. There was little he could do but minimize excess movement and walk directly toward the feature he had seen in the distance. As soon as he had left his rocky perch, Tchict’Ict had lost sight of the line, but he relied on his acute sense of direction to guide him in a straight path, which would eventually intersect the line for which he made.

So it came to pass. Crossing an expanse of rocky terrain, Tchict’Ict arrived at this line and found it indeed to be artificial—a road, about six feet wide, from which the small pebbles had been kicked away by previous travelers, leaving a smooth surface of a slightly different shade (a little more gray in the brown) than the surrounding rock. It was this change in color and texture which had caught Tchict’Ict’s keen eye from afar.

Although Tchict’Ict found no clear foot prints, there were signs that some sort of traffic had moved along this road. In the still air, it was difficult for Tchict’Ict to judge how recently the last traveler has passed. Because there was no breeze to cover the tracks with dust, it could have been a day or a hundred years since someone had last trod upon this road. Standing in the middle of the flat road, Tchict’Ict again patiently inspected both directions. The road disappeared into a featureless horizon to the left and much the same to the right. Tchict’Ict judged that the unusually pointed rock was located to the right of the point where he had met the road. Finding no more compelling evidence, Tchict’Ict turned right and proceeded down the stone road.

Tchict’Ict walked for a shorter distance than it had taken him to reach the road before his eyes spied the pointed rock, elevated above the road. As he drew near, he first discovered that the rock was of a darker hue than the surrounding stone. Gradually, he began to make out further details until he was close enough to observe that the rock was in fact the pointed roof, shingled in slate tiles, of a modest two-story structure.

The building, built of an ebony wood, was square in footprint, perhaps no more than thirty feet in each direction. Upon a small, covered front porch, a narrow, black door stood. Three steps descended from the porch to a short, dirt path leading to the side of the road. The house bore numerous windows on all sides and positioned on both floors. The glass appeared a pale yellowish-brown, in places almost coppery, and revealed nothing of the shadowed contents within. Tchict’Ict noted that his first impression of the house as dilapidated proved incorrect. The boards were straight and tight, the gaps between them narrow. It, apparently, had been only an illusion of the distance that this house was in a state of decay.

All of these observations Tchict’Ict made while still more than a hundred yards down the road. As he drew closer, he focused all of his attention on the lone figure standing in the middle of the road in front of the house. The creature was roughly man-sized and garbed completely in black armor. Metal boots covered his feet and greaves covered his legs. Similarly armored were his torso and arms. Upon his head he wore a black helmet. His face was entirely obscured by a lowered black guard bearing eye slits, revealing only shadow within. The right arm hung at its side, empty. From the left hand, the black knight held a wicked flail. The ornate rod ran two feet long, decorated with an obsidian stone at the back end and carved along its length with black runes. From the front end of the weapon, six chains hung, each ending in small, spiked barbs, each carved in the shape of horned heads.

Tchict’Ict stopped when he stood ten paces from stranger. Alone on the road, the insect-man and the black knight faced each other. Silently, Tchict’Ict judged his adversary. In his appraisal, the black knight appeared to be no less corporeal than Tchict’Ict himself. In any other world, he would have surmised that such extensive armor provided defense at the expense of speed and agility. However, in this world of the dead, Tchict’Ict wondered if such rules applied. Regardless, the presence of the knight blocked the road in an undeniably combative stance.

Tchict’Ict remained still. The knight made no motion, however minute. For a moment, Tchict’Ict considered the possibility that he had mistaken a statue for an enemy. No sooner had the thought crossed his mind than the black knight spoke.

“I am the guardian of this road.” The voice of the black knight was deep and somber, resonating with a metallic tin from within the armor.

Tchict’Ict sensed in the formulaic statement, the beginning of a prescribed ceremony. Well versed in the ritual of routine, Tchict’Ict replied, “I am a traveler upon this road.”

“Are you living or dead?” replied the knight.

“I yet live.”

“Then you cannot pass,” finished the knight. Through the short conversation, there had been no movement whatsoever from the knight. Having completed the conversation, it continued to remain perfectly still.

Tchict’Ict had no intention at the moment of passing the knight. He had come to investigate a distinguishing feature in the otherwise unremarkable landscape.

He needed information. “I do not intend to continue along this road,” said Tchict’Ict, which was true, at least for the moment. “What is the purpose of this house?”

The black knight has stood for untold eons upon this road. Although he had no obligation to discharge any duty save that of blocking the road, neither did he have any command preventing him from further engaging any traveler along the road. This particular traveler was of a kind entirely unknown to him. The black knight, whose purposes remained hidden to us, chose to respond with a question of his own.

“What manner of beast are you?”

“I will answer your question only if you answer my own,” replied the insect-man.

“Agreed,” said the knight. “A question for a question. I shall begin. What manner of beast are you?”

Tchict’Ict chose his words carefully. Since he understood that he was engaged in an information exchange, he added some depth to his answers, hoping to elicit a similar response from the knight, when its turn came. “I am what others call an insect man. I was a ranger of my people. When my colony was lost, I became a traveler far and wide. My travels have led me to this place.”

When Tchict’Ict finished speaking, the knight revealed that he was capable of motion, nodding in acceptance of the answer. “Ask your question,” said the knight.

Given the opportunity, Tchict’Ict chose a different question than that which he had first asked. He sought first to better understand a possible foe. “What manner of beast are you?”

His question gave the black knight pause. “I am the guardian of this road,” it replied again, as if there was nothing more to its being.

Tchict’Ict shook his head. “That is an unsatisfactory answer. You do not honor our arrangement.”

The black knight replied, “I am nothing but honor and duty.” Although the knight’s expressionless voice was incapable of outrage, Tchict’Ict sensed it all the same. There was no greater injury to a knight than a besmirchment of its honor. “Perhaps, I did not understand your question. Clarify.”

Tchict’Ict asked then, “Are you an angel?” He can be forgiven for the absurdity of this question because, as we have already noted, Tchict’Ict possessed no cultural understanding of the afterlife.

The black knight for his part again seemed baffled by this question. After an unusually long pause, he replied in the same emotionless, metallic voice, “I am not counted among the angels, who dwell in the seven realms of Heaven.” The knight then asked, “What is your purpose in coming to this place?”

“I am seeking a friend,” Tchict’Ict answered. “Are you devil or demon?”

This time the black knight showed no hesitation in answering the question; he had apparently already adjusted to the sort of questions with which an insect might ply him. “I am neither ranked among devils, who, by contract, reside in the nine circles of Hell, nor am I unnumbered as the demons, who run mad in the six hundred sixty-six layers of the Abyss.” For a moment, Tchict’Ict thought the knight would say more but what came forth was just another question. “What is your name?”

“I am called Tchict’Ict by the company with whom I now travel. In my native tongue, I was called...” At this point, Tchict’Ict produced an unrenderable chittering. He then asked, “What is your name?”

The knight replied, “I am called Immortui Umbra, although this is not the name by which I was always known.” The knight paused, considering that Tchict’Ict had (rather rashly) revealed his true name. He was, by etiquette if not honor, obliged to provide the same. “My previous name,” said the knight, “has been taken from me and is beyond my recall.” Even this limited admission conveyed more information about his station than was wise, or so thought the knight. “Do you seek to reclaim a friend who has passed into death?” The knight asked this question for confirmation only. It was virtually the only reason any living creature ever ventured into the World of the Dead.

“No,” Tchict’Ict replied, “my friend has not died.” Tchict’Ict continued, “If you are not angel nor devil nor demon, Immortui Umbra, then I ask again what manner of beast are you?”

The black knight now clearly understood the nature of Tchict’Ict’s question. He answered more fully. “I am Immortui Umbra, an unending shadow, the guardian of this road. I am what is called among the living a revenant, brought unwillingly back to life by one with knowledge of the arcane secrets binding life and death, in order to do his will, which, in my case, is to guard this road.” The knight now asked, “If your friend has not died, then why have they come to the World of the Dead?”

“We pursue one who had died,” Tchict’Ict replied. “But we were separated upon our entrance to, as you call it, the World of the Dead.” Tchict’Ict asked, “This road seems empty. What do you guard against?”

In this even exchange, both Tchict’Ict and Immortui Umbra gained much information as well as understanding of each other. The knight now answered, “I guard against the living, one living in particular. What is the name of the one you pursue?”

“The Deadly Galerina, a god among mushrooms.” This next question came unbidden to Tchict’Ict. “What is the name of the one you guard against?”

“Poison Pie, a man of the mushroom people,” stated the black knight. “Do you know him?”

Fearing to betray his companion, Tchict’Ict paused. Just as was the case in Faerie, a lie in the World of the Dead carried its own weight and created its own unintended fortunes. This pause provided its own answer to the knight’s question.

Immortui Umbra stated with finality, “I think we have no further need of questions, Tchict’Ict.” The black knight announced to the stone road and the black house beside, to the scattered rocks and the ominous smoke overhead, “Poison Pie has finally come to the World of the Dead. My wait is over. I will call him to this place and he will come.” The tone of the black knight’s voice changed, as he addressed the insect-man again. “You are welcome to wait inside with me. It may take some time.” The knight gestured with his empty, gloved hand toward the house.

The steps of the knight clanged against the stone road as he strode to the dirt path, before ascending the three steps and opening the black door into the house.

Tchict’Ict proceeded down the road until he was level with the path. Peering past the knight, into the door, Tchict’Ict saw a room illuminated by the bleak light of the sky filtered by the brown glass into waves that undulated across the interior walls. Tchict’Ict knew his odds for survival were better in an open space where he could take full advantage of his speed but he also judged that he could extract additional information from the knight, who clearly knew more than he had thus far revealed.

Despite his grave misgivings, Tchict’Ict approached the porch. The black knight entered the house. The door stayed open behind him. Tchict’Ict climbed the stairs. From the porch, he leaned over into the doorway and inspected the room. Immortui Umbra stood in the middle of the room. Above him a glass chandelier hung. Six candles were lit and gave off a light that struggled weakly against the pervasive darkness of the World of the Dead. Interestingly, the room seemed to be much larger on the inside than the exterior walls would have allowed. Numerous passageways and staircases led from this room hinting at even greater spaces within, in obvious excess of the dimensions of the house. The floor of the room was laid with ebony wood. Through this room, various pieces of wooden furniture were spread. Several hexagonal wooden tables, each with five chairs and one empty place, were distributed across the room. On one side, several divans, upholstered in black fabric, were arranged around a central low table. It seemed a kind of lounge, though vacant and bleak indeed. Tchict’Ict entered the house.

Immortui Umbra led him to a small, though high table near a front window. On opposite sides of this table the knight and the insect stood. Through the coppery glass, Tchict’Ict had a clear view of the road.

“We will see him coming from here,” said the knight.

“How will you call him?”

“I am a revenant, one of the undead. That which created me also granted me the authority to command other undead.” Immortui Umbra turned the faceplate of his helmet toward the numerous empty chairs and sofas within the room. To Tchict’Ict’s amazement, all of the seats were now occupied by hazy, spectral beings. Each had a unique appearance, bearing some resemblance to the individual who they had been prior to their deaths. Most were of some mammalian, humanoid race—men, elves, dwarves, gnomes, even a misplaced dog-man. In the folds of their shadows, Tchict’Ict periodically caught a glimpse of the ghostly remnants of the trappings of their lives, the pattern or straps of a dress or the leather of a belt.

“What are these apparitions?” Tchict’Ict asked.

“They are wraiths,” answered the black knight.

“Go,” Immortui Umbra commanded the undead host. “I send you out to scour these lands. To any living creature you meet, extend my invitation.”

The ghosts as one rose and began to glide across the black floor and out of the house.

“What will your invitation say?” Tchict’Ict asked.

“You truly have no understanding of the World of the Dead,” said Immortui Umbra.

“I do not,” Tchict’Ict plainly admitted. In his defense, he had never pretended to have any.

“Although I remember little of my life, I do know that I lived always bound by honor,” said the knight. “It is therefore with great regret that I confess to you, Tchict’Ict, a fellow being guided by honor, that in undeath my greater master is the command set upon me by the one who summoned me from the shadows. Although it is most onerous to concede, I have betrayed you. I have, through low deceit, led you into a House of the Dead, from which there is no escape.”

The last wraith exited the building and the front door slammed shut.

Tchict’Ict sought expression in the impassive armor standing across the table but found nothing.

“The invitation I extend will read thusly,” said the black knight, “Poison Pie, I hold your good companion, Tchict’Ict, as my guest. Should you wish to share his kind company once more, come seek him at my house.”

|

|

|

|

|

July 21, 2014

“You are not the ghost of the Tuinman,” said Princess Pie.

“No,” Celia agreed, “I am not.”

“You are not a giant of Faerie,” said Princess Pie, “though you look like you once were.”

“Again, you are right.”

“You are no more a ghost than you were a faerie,” continued Princess Pie, “Isn’t that right, Celia?”

Celia allowed a well-intentioned but hideous smile to flash across her disfigured face. “I wondered if you would see past the disguise.”

“You are a changeling,” said the faerie, with a tinge of accusation for having been fooled for so long. “But you have powers beyond that of other changelings.”

“No,” Celia replied, “there is nothing special about me. I only allowed the natural magic of Faerie to guide my previous transformation just as I have allowed the ubiquitous death pervading this place to channel my form now.”

“Frankly,” said Princess Pie, “I preferred the faerie.”

“As did I,” Celia readily conceded.

The faerie and the ghost found themselves in the midst of a flat expanse of indistinguishable rock. As had Tchict’Ict, they surveyed the land in all directions looking for signs of their lost companions. Eventually, Princess Pie came to rest on the ground, something Celia had never seen her do in Faerie. Even after the attack of the undead crows, the faerie had maintained her flight, albeit in close proximity to the ghost who had rescued her. “Is something wrong?” Celia asked.

“This place saps my energy,” Princess Pie admitted. “The sooner we leave the better.”

“It doesn’t seem to affect me as it does you, at least in this form,” Celia admitted, “but, all the same, I have no desire to stay here any longer than absolutely necessary.”

“It is rather dreary,” Princess Pie noted. The faerie repeatedly suggested that a ghost ought to have some preternatural intuition about the World of the Dead. Celia attempted to meditate to gain some clarity in this regard, but whatever characteristics may have come with the form she had assumed, an instinctive knowledge of Poison Pie’s whereabouts was not among them. Consequently, they wandered.

Princess Pie sometimes walked and sometimes performed pitiful little hops, enlarged by a few beats of her wings, to keep pace with Celia’s gigantic strides. She often dragged her star lantern beside her as if it contained a great load. Celia, of course, could not carry the faerie for the one was insubstantial while the other possessed a physical body. In Princess Pie’s increasingly exhausted and erratic steps, the outlines of their forms sometimes overlapped with naught but a shiver down the spine of Princess Pie to show for it.

By the time, the bearer of the Immortui Umbra’s invitation arrived, Princess Pie was dragging her feet and Celia had already admitted that voluntarily entering the World of the Dead had been a dreadful, perhaps fatal, mistake.

The unholy wraith approached them, gliding above the stone, drawn to their warmth like a shark to blood. Its very presence inspired fear almost to the point of nausea. Coming to a rest before them, it sang its song verbatim to that which the black knight had recited within the House of the Dead, in a ghastly voice, full of undirected hate.

That the only two names mentioned in the short song were Poison Pie and Tchict’Ict elicited a mixed response from the two women who heard it.

Perversely, it imbued Princess Pie with new energy. The seemingly endless, listless wandering was at an abrupt end. A compliant though certainly unpleasant guide sought to lead them straight to Tchict’Ict. Poison Pie, if he wasn’t there already, would be there soon. Princess Pie saw a light at the end of this miserable tunnel and her inherently optimistic outlook prompted her spirits to rise.

Celia, on the contrary, listened to the words of the wraith’s song more carefully. Even as she and Princess Pie followed the loathsome wraith, she tried to make sense of the words. Someone held Tchict’Ict as its guest and was using his presence to lure Poison Pie. This meant something in the World of the Dead knew of Poison Pie. How much did they know? It was true that in Nirvana, Sariputra had a package waiting for Poison Pie, but Celia deemed it most unlikely that a second such fortunate encounter lay in store. She wanted the exact words of the song repeated, in order to search for hints or threats in the nuances of the wording. Celia therefore asked the wraith to repeat the song, but the undead creature paid her no mind, turning only to make certain that her cargo was still in tow.

Upon further consideration, Celia was certain that the message hadn’t said that Tchict’Ict was a prisoner. There hadn’t been any direct statement of threat, as she recalled. Still, those who employed the undead as servants would be unlikely agents of peace. Perhaps it was just the appearance and tone of the messenger that left Celia feeling certain that something evil had captured Tchict’Ict and was using him as bait to trap Poison Pie. As they followed the wraith, it occurred to Celia more than once that the trap might prove no less effective against Princess Pie and herself.

|

|

|

|

|

July 21, 2014

The process by which the World of the Dead extracts the biochemical energy of life from the living was greatly accelerated within the confines of the House of the Dead. By the time Princess Pie and the ghost of a faerie giant came into view, the body of Tchict’Ict was completely paralyzed. He could not move his jaws to speak nor could he turn his head. However, his wide-set eyes bestowed a broad range of vision and he remained standing at the table at the window in a position with a clear view of the road.

Immortui Umbra too had remained standing at the table, while the onset of petrification, the first stage of the transformation from the living to a wraith, had overwhelmed Tchict’Ict. He felt he owed at least this much to the insect man. Observing the new arrivals, the black knight stepped away from the table, almost apologetically excusing himself from the company of the one who could not be excused. “We have company.”

Immortui Umbra left the House of the Dead and crossed to his familiar position in the stone road. The wraith hovered to the side. Before him, now stood a bedraggled faerie with drooping wings and a creature that appeared as the ghost of a giant of Faerie. Immortui Umbra, revenant that he was, could well distinguish between the living and the dead, no matter how sophisticated the disguise. He saw the creature for what she was, a changeling girl, talented and inventive, but a mere changeling all the same.

Immortui Umbra was in very poor spirits when he perceived that neither of the living creatures led by the Wraith were Poison Pie. The black knight knew Poison Pie to be a man of the mushroom people. Neither of these new arrivals were male nor were they remotely fungal. Revenants are not given to sighing, but if they were, Immortui Umbra would have then released such a sigh as had never been known before, for the remains of his heart were heavy with the evil demands placed before him. It had not been enough to encounter a creature of its word and, through trickery, lure it into an eternal damnation of undeath. He would be forced to crush the innocence of a faerie and irreversibly warp a changeling into a form it had never desired nor deserved.

What words of consolation could he offer these poor travelers? He said only, as he had before, “I am the guardian of this road.”

It was Princess Pie who ignored the greeting and pointed a weak arm at one of the copper-colored first-floor windows. “Itchy,” she said.

Celia observed the static image. It reminded her of nothing so much as a bug trapped forever in the warm but unyielding light of amber. She recognized that she was too late, but Celia refused to capitulate so easily.

To the black knight, she announced. “I am a monk of Flying Cloud Cave on Dragon Squeezing Mountain. Every instant of my life has prepared me for this moment. You have no defenses that can stand against me, an instrument of the will foretold. Release the insect-man and the mushroom man too, if you hold him as well, and I will allow you to flee with your miserable lackey. Stay and you shall be destroyed.” At the mention of the insect-man, Celia had gestured with her withered arm toward the window in which Tchict’Ict was framed. At the mention of the lackey, she gestured with her good arm toward the wraith.

It was worse than Immortui Umbra had guessed. It was always worse. He now had to put down a holy woman. In his death, the black knight did not possess the imagination required to invent an alternative outcome. Assured of the inevitability of the actions that would doom him no less than it did the monk, Immortui Umbra stepped forward, raising the six-barbed flail.

What the revenant had not anticipated was the resiliency of faeries. Princess Pie gathered her last reserve of strength and sprang into the air. She shouted at the black knight words, which brought him to a staggering halt. “You coward. I have seen with my own eyes the fight in that bug. I do not believe you possess the strength to have bested him on equal terms. If you did, I would not find the bug in one piece, standing so neatly at the window, for he would have fought until you had stripped him of his chitinous hide with your fell whip. Thus, I see as clearly as if I had been here in witness that you defeated him only through treachery. I see you are a creature, sunken and depraved, who knows no honor. What new trick will you use to lay low this monk? Will you plead for mercy when she wrings your iron skin in her grasp? Will you lure her to your house of suffering with promises of reparations? Oh, evil one, belabor us not with your indignities. Such disregard for honor is but common in the world. We have already seen too much of it. Begone from our sight!”

It is an incontrovertible fact that before this creature was Immortui Umbra, it was something else, and before that another something else, and so on, through previous incarnations. It is for good reason that typically, in the cyclical process of reincarnation, the characters of two consecutive entities are not so disparate from each other. The karmic process of reincarnation results in incremental changes, to which the individual can readily adjust. In Immortui Umbra, this glacial process had been hijacked through unnatural intervention. The most recent two incarnations stood at incontrovertible odds to each other. There was no reconciliation to be found between them. While the black knight now ruled the body, such as it was, the foundation upon which that body stood was made of an entirely different substance.

Immortui Umbra willed the suit of armor forward. The substance within resisted. The substance from which Immortui Umbra had come now issued a fervent and humble prayer to be granted the strength to destroy who it had become, even at the expense of all that it had once been.

With a spastic jerk of his arm, Immortui Umbra struck the faerie from her hovering position, sending the star lantern flying and knocking the faerie unconscious when she fell against the stone.

The monk leapt forward with dizzying speed and slammed a giant fist through the chest of the black knight, but met with no resistance. The armor of Immortui Umbra granted him substance, an inviolate protection against the incorporeal.

His whip however possessed a curse, common to this kind of hexed instrument, which allowed it to strike in both worlds, delivering injury to both the living and the dead, corporeal or bodiless. Before Celia could recover her balance, Immortui Umbra raked her back with the flail, tearing six long furrows in her luminous flesh.

That a ghost could know such pain had never occurred to Celia. She instinctively searched for that monastic training which would allow her to subjugate the pain to her will. She stifled the shriek of agony that had threatened to escape her but stumbled to her knees.

Immortui Umbra, intent on his own doom and struggling against an internal prayer of self-destruction, lurched forward to strike Celia again.

The black knight was unprepared for the agility of the deformed giant. Celia spun and, summoning all her strength, ripped the flail from his grasp.

Too much of his power had been poured into that weapon. Alternatively, some deity, less uncaring than the others, heard the desperate prayer of that which had become Immortui Umbra.

In the instant before Celia struck the black knight with his own flail, the joints of the armor simply seized up, preventing any attempt to evade or deflect the blow. The full might of a giant brought the flail down upon the chest of the armor, piercing it in six places and shredding gashes through the metal. Immortui Umbra, an unending shadow, ceased to be. A darkness issued from the damage armor and dissipated in the surrounding darkness of the World of the Dead. A gruesomely dented suit of iron armor collapsed upon the road.

The monk, a ghost with six jagged wounds from which thick blood coursed down her back, tossed the weapon from her in disgust and dismay. She shuddered and, losing her balance, fell to the ground, sitting beside the figure of twisted metal.

How do we know such violence unfolded outside the House of the Dead? We cannot attribute the primary authorship of this tale of woe to Princess Pie who lay, at the end of her strength, blissfully unconscious. Nor can we identify Tchict’Ict as the source since, while his eyes were opened, his body was petrified. Indeed, only the wraith who brought Celia to the knight bore witness to this violent exchange. That wraith surely retold the tale many times among the dead, for whom tales of unredeemed annihilation are highly valued. Eventually, the story must have made its way to the world of the living, perhaps through a medium conversant in the ways of communicating with the dead. Surely we cannot attribute the retelling of this story to the monk, who never even knew the name of Immortui Umbra and who certainly never spoke of the violence contained in her moment of weakness.

|

|

|

|

|

July 21, 2014

Poison Pie and the ghost of the Tuinman never received the invitation of Immortui Umbra. When the revenant was extinguished, the wraiths, free of their command, dispersed without any regard for the fact that their job remained incomplete. All the same, Poison Pie arrived at the House of the Dead for the simple fact that the ghost of the Tuinman had a nose for mushrooms and this road was the only road that led to the entrance to the Mycomantle, where the Deadly Galerina, upon its death in Faerie in ages past, had fled.

What did Poison Pie find at the House of the Dead? The reader knows very well what he found, but we shall list them all the same. First, he found a long stone road leading, it appeared, to nowhere in both directions. Next, he found a six-barbed flail, a weapon so fell he dared not even touch it. Third he found a heavily damaged suit of black armor. Again, the taint of evil lay so thick upon that metal that Poison Pie kept a safe distance from it.

Beside the armor, Poison Pie found the ghost of a giant of Faerie. The incorporeal creature was badly injured. Its back was caked with congealed blood. It made little sense to ask if a ghost was dead but of his gardening companion this Poison Pie did ask.

The ghost of the Tuinman examined the bloody form and, after some moments of consideration, replied, “Just resting, I think.”

In Poison Pie’s defense, let us remind the reader that Poison Pie entered the rift first. He had no way of knowing that any of the others had followed him. When no one but the ghost of the Tuinman appeared beside him in the World of the Dead he had every reason to believe that they were the only two who had left Faerie. Poison Pie pleads with me, as narrator, to extract from the reader the concession that this was a reasonable conclusion, was it not? He would not have knowingly failed to come to the aid of those who sought to protect him. On this point, he must insist.

So, he was surprised to find a faerie, limp and unresponsive just off the side of the road. She was not dead for she still possessed a physical body. As he knelt over her, Poison Pie’s confusion grew by bounds when he recognized Princess Pie.

He tried to assemble the puzzle but too many pieces were missing. His gaze shifted back to the second giant ghost. Perhaps the fight had continued in the corpse of the Deadly Galerina, after Poison Pie and the gardener had left. Perhaps, Tchict’Ict had slain another giant. Why had Princess Pie come through in the company of the ghost of this giant? There was no reason to believe that Poison Pie should have recognized Celia in this form.

A short distance from Princess Pie, about half way between where she lay and the porch of the house, Poison Pie found her star lantern. Only a faint flicker remained within the silver frame. He knelt, picked it up and stood. At that moment, his gaze met that of Tchict’Ict frozen behind the amber window. He stood just as still as Tchict’Ict, evenly matching the gaze. Perhaps, if he imitated Tchict’Ict long enough, the insect man would begin to imitate him as well and begin moving. Poison Pie’s hopes proved untenable; the immobility of the insect man outlasted the mushroom man’s patience.

Poison Pie set the lantern back down. He climbed the steps of the black house, though he had no desire to approach it. He strode past the black door and stood directly in front of the window in question. If Tchict’Ict was a foot behind the glass, Poison Pie was a foot in front.

This puzzle piece made even less sense than the others. In the House of the Dead, his friend was petrified.

Poison Pie tried opening the black door no fewer than one hundred times. He beat on it with all the might in his curled mitts, but the door neither creaked nor groaned. He rammed it with his shoulder but the boards seemed possessed of an unearthly strength and would not give. Poison Pie took up the dread flail though it left a black char on his mitt and struck and restruck the windows of the House of the Dead—first the one on the far side of the porch and then the one behind which Tchict’Ict silently peered. The barbs could not scratch the amber glass. The House of the Dead was permanently sealed, an impenetrable and indestructible mausoleum. There was no power known to any of those assembled which could undo the last dark work of Immortui Umbra.

Poison Pie jumped from the porch into the road and, releasing a bellow, hurled the flail as far as he could. It landed with a dull, lifeless clatter, skittering across the rock. Poison Pie knelt over Princess Pie and gently nudged her, urging her to wake. She might have a magical solution to freeing the fighting bug. He placed the tiny star lantern in her grasp but still she did not respond. All his ministrations and urgings were for naught.

Next Poison Pie knelt beside the wounded ghost of the giant. He could not interact with that body, so he howled at it to wake up and provide the explanation for the ruin that he found here. He accomplished nothing. He pleaded with the ghost of the Tuinman to rouse his dead kin. The ghost of the Tuinman poked the shoulder of the wounded giant with a withered finger, which produced no response. At Poison Pie’s urging, the ghost of the Tuinman shook the shoulder of the wounded giant, but could not interrupt her slumber.

The ghost of the Tuinman shrugged. “I don’t understand.”

Although Poison Pie never sought understanding, he refused now to accept this reply. “You are dead,” he shouted at the ghost of the Tuinman. “This is your place.” The man of the mushroom people waved his arms about wildly gesturing at the sky and the rocks and the accursed house. “Tell me what is going on here!”