|

|

|

|

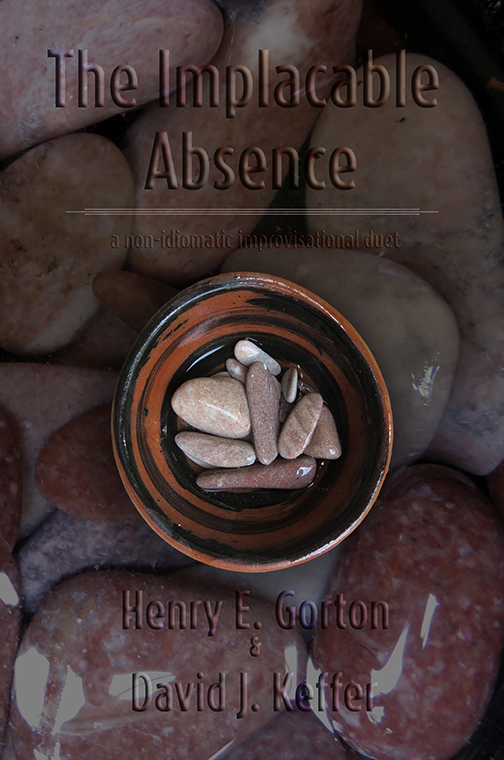

The Poison Pie Publishing House presents:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Implacable Absence

A Non-Idiomatic Improvisational Duet

Henry E. Gorton & David J. Keffer

(link to main page of novel)

January

|

|

|

|

|

1. The Surface World

|

|

|

January 15, 2014

The collision of the Andromeda and Milky Way galaxies, the two largest galaxies in the Local Group, is predicted to occur in about four billion years. While Andromeda contains about one trillion stars and the Milky Way contains about three hundred billion stars, the chance that even two stars collide is negligible because of the huge distances between the stars. Even at the denser galactic centers, the average distance between stars is one hundred sixty billion kilometers. Thus rather than spectacular head-on stellar impacts, the event will be celebrated with a gradual deformation and rearrangement of the celestial contents. The Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies each contain a central supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A* and an as-of-yet unidentified object in Andromeda's nucleus, respectively. These black holes will converge near the center of the newly formed galaxy, where, over millions of years, they will, through gravitational interactions, transfer stars to higher orbits. When the black holes arrive within one light year of each other, they will emit gravitational waves eventually resulting in a complete merger. Simulations indicate that the future Earth might be brought near the center of the combined galaxy, potentially approaching the black hole before being ejected entirely from the new galaxy.

—adapted from wikipedia

|

|

|

|

|

January 15, 2014

The envelope itself seemed rather inconspicuous, rectangular and white, well-disguised as any other ordinary letter might appear. Most unusual, however, about this particular envelope was the individual to whom it was addressed: a Mr. P. Pie.

“Mister Pea Pie,” mumbled the addressee in the most disagreeable tone his deep voice could muster. Standing on the porch in his burlap pajamas, he pondered the impossible letter. No one in the history of everything had ever sent him a letter. Who dared? His loathing of correspondences of all sorts—telegrams, electronic communiqués, mail of any kind—was widely known. Mister Pea Pie held the written word in low esteem in large part due to his almost complete absence of training in the art of reading. It pushed his abilities in this regard to manage even so much as “Mister Pea Pie.” Who dared provoke his rage in this poorly chosen and decidedly uncouth manner? A coward to be sure, for there was no return address.

Mister Pea Pie destroyed the letter because, of course, destruction was one of his favorite calling cards. He first crumpled the letter, crushing it inside two massive fists, which more resembled aged, leather catcher’s mitts in size, shape and texture than they did human hands. He tossed the letter to the muddy stone path and ground it beneath the sole of an enormous foot. It occurred to him that destruction by mastication was also appropriate in cases such as this. Examining the dirty, shredded wad of paper, he supposed that mastication should have preceded grinding under foot, but...oh well! Mister Pea Pie was not one to shy away from duty based on the niceties of social convention, so into the gaping mouth the remains of the letter went. He chewed for some time on the fibers of the paper, the ink of the message mingling with saliva. Eventually he swallowed, internalizing the message. Having observed this, can it be said that he did not receive the letter?

|

|

|

|

|

January 15, 2014

A boy, a genuine flesh-and-blood boy, of the village had the temerity to approach Mr. P. Pie, or Poison Pie, as he was more casually known, and shout from the safety of the edge of the clearing surrounding the house at the figure kneeling in the garden, that the parson requested his presence. Poison Pie could no more have expected this summons than he had the letter earlier that morning. Since bad news traveled in threes, he could be sure that the parson had a nasty surprise waiting for him.

Poison Pie’s first impulse naturally was to destroy the God-forsaken parson and his holy house in one fell swoop. He stymied the impulse, not because he harbored the unrealistic hope that, come judgment day, a monster such as he would be ranked among those deemed worthy of salvation, but rather because the stones in the church were old river stones, stones he had known ages earlier when they still felt the action of the cold current on their smooth faces, stones that he knew by name, and whom he could implicitly trust never to send him a letter. For their sake, he spared the parson.

Poison Pie carried to the church exactly two buckets of river water, one hung from either side of a pole borne on his shoulders. Stopping at the right side of the front stairs, with a great heave he splashed the contents of one bucket on the stone walls, then moved to the left and emptied the second bucket. An observer summoned the parson with an erroneous report that the mushroom man was defiling the church with an unholy ablution of fungal fluids.

“Pie!” shouted the parson, racing as fast as his stout legs would carry him to arrive panting ten feet from the hulking hermit. Of this creature, the parson knew very little, only that he was an infidel, neither tithing nor attending services and was not to be counted among the faithful of his flock, and that he lived alone in a dilapidated shack at the edge of the great forest on the outskirts of the village. The man, such as he was, turned his gaze to the parson, who immediately averted his eyes from the unpleasant spectacle before him. It was true that Poison Pie was an ungainly amalgamation of unusual height, swarthy skin, and an affliction of bone that had reshaped his hands and face into forms not common among men. More disturbing than any visual disfigurement, however, was the aura of malaise that emanated from him. Something was undoubtedly wrong with the creature beyond any physical description.

“Pie,” the parson repeated, recovering his breath as he stared at the ground. “Someone...” he started, “...surely mistakenly...” he added, correcting himself. He sputtered to a halt and dared a glance up at the giant, whose black, deep set eyes peered down at him from beneath the brow of bone with what seemed a withering condescension. In a rush to have the ordeal over, the parson managed, “Someone left a parcel for you in my church.” He added by way of apology, “I have no idea why.”

“How do you know it’s mine?” Poison Pie asked in his deep, somber voice.

“It’s addressed to Mr. P. Pie,” answered the parson.

“Give it to me,” said Poison Pie, holding out a mitt.

“I shan’t touch it,” said the parson.

During this short conversation, a small crowd had gathered around Poison Pie, who was rarely seen in the village, and the parson.

“Is he giving you trouble, Father?” shouted a newcomer, with a confidence bolstered by numbers. People began wondering if they shouldn’t hurry back to house for shovels and pitchforks.

The parson waved them off. “Go back to your work,” he told the villagers. Eventually, after the parson’s repeated admonitions, they dispersed. Not until the last one left, did the parson speak again to Poison Pie. “I shall not touch that package,” he repeated.

“I’m not welcome inside your church,” Poison Pie replied.

“Indeed,” agreed the parson.

They might have stood there the rest of the afternoon, paralyzed by restrictions placed upon them for reasons the other did not understand, but for the parson’s desire to escape the creature’s wretched company. “Just run in and grab it,” whispered the parson.

Poison Pie gave a long, slow shake of his head. “I’m not welcome,” he repeatedly stubbornly. “Go get it for me.”

“I shan’t touch it,” said the parson for a third time, now with a tone of exasperation. He waited intently for Poison Pie to ask him for the reason why he would not touch the parcel, but he did not understand that for Poison Pie the world, and all activities within, moved without reason. No such question as “Why?” could emerge from those lips. Finally, the parson offered, again reduced to a whisper, “It’s thumping.”

“Thumping?”

“Your parcel is thumping.”

“Like a drum?”

“Like a heart.”

“A heart?”

“A heart suffering from arrhythmia.”

“I don’t understand,” Poison Pie admitted.

“Nor, do I,” said the parson, moved despite himself to a sympathetic tone. He quickly restored a measure of authority and announced, “I want that thumping parcel out of my church.”

“You won’t touch it,” Poison Pie said, “and I won’t enter.” Unable to conceive of a resolution, Poison Pie turned and lumbered back toward his home.

“Where are you going?” the parson called after him.

Poison Pie paused and turned. “Home.” He was sure that whatever lay packaged within the parcel was the third of three nasty surprises. He felt a pleasant sensation at the idea of leaving it with the priest. He turned again and took another step toward home.

“Have your man come fetch it,” the parson hollered after him.

Poison Pie stopped again. Facing the parson from this distance, he asked, “My man?”

“Do you have a manservant?” the priest asked, now aware of the absurdity of the question.

“I have a host,” Poison Pie replied. “who answer to me, to a man. Are they welcome in your church?”

“Absolutely not,” replied the parson without hesitation, adding, “under ordinary circumstances. However, I will make an exception for the immediate removal of this parcel from my church.”

“My men are invited to church,” Poison Pie sang in a gravelly tone as he marched to the edge of the church. He leaned his forehead against a river stone lodged in the wall. He placed his mitts at roughly the same height on two other stones. He called forth a host of Men of the Mushroom People from shallow beds beneath the Earth’s surface to rise up through the wooden planks of the church, sprout like a rippling wave of mushrooms from the vestibule to the altar, before which sat the parcel. There they would fruit beneath the parcel, lifting it on shoulder and cap and carrying it on an undulating wave back to the entrance from which it would be unceremoniously ejected into the street.

It’s difficult to place a finger on exactly which part of these actions took place, for Poison Pie was not inclined to rely solely on his senses to relay information to him regarding the state of the physical world. He preferred, greatly preferred at times, to allow his imagination to dictate a description of the external world. So, if queried on the matter, Poison Pie might suggest that the parcel was delivered to him via the means described above.

The parson, on the contrary, might suggest a substantially different sequence of events, centered primarily around the same rapscallion that had delivered the original message to Poison Pie. This boy had hidden himself, since before the arrival of Poison Pie, beneath the church’s wooden steps. He had overheard the entire conversation. As he peered through a crack at the concentration on Poison Pie’s misshapen face summoning the Men of the Mushroom People, the boy succumbed to the urge to leap from his hiding place, race into the church, grab the throbbing parcel in his hands, and throw it mightily into the street.

The truth, of course, lies somewhere between the descriptions of Poison Pie and the parson. The Men of the Mushroom People filed into the church from which they were ordinarily forbidden. They chose not to hasten their departure through the brisk completion of their task. Instead they filled the pews and prayed to the Deadly Galerina, one of the Uncaring Ones Who Dwell Above The Stars and who control the fates of man and beast; this particular one predisposed to denizens of the Kingdom of Fungi. While their ranks engaged in reverent supplication, the gaze of the Deadly Galerina swept into that church. Espying the urchin beneath the stairs, the spirit of the Deadly Galerina crept inside the boy and prompted the delivery of the parcel to the proud and unrepentant Poison Pie, who picked it up and sauntered home, leaving the Mushroom horde to gradually disassemble on their own. The credibility of this sequence of events is bolstered by the fact that during the parson’s subsequent interrogation of the boy, the poor child confessed to having no memory of his actions.

At home, Poison Pie deliberately opened the package, which contrary to the parson’s repeated description, betrayed no signs of thumping whatsoever. Inside he found a heart, somewhere between the size of an apple and a grapefruit, carved from polished marble of a pale pink hue. Not surprisingly, the gift meant nothing to Poison Pie.

|

|

|

|

|

January 16, 2014

Gnomes no more exist than do Men of the Mushroom People, at least according to the scholarly writings of learned men. While there may be debate among those with lesser and greater extents of education regarding the existence of gnomes, there is one point upon which they can all agree, namely that gnomes, real or fictional, are much maligned. No greater slander is done them than the long-standing claim that they owe their origin to the sixteenth century occultist, Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (PATBvH), who is today better known (if he is known at all) by the sobriquet, Paracelsus, which he adopted to signify that he considered himself the equal of the first century encyclopedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus. In selecting such a nickname, PATBvH revealed a rather unimpressive degree of insecurity with respect to his own accomplishments and displayed an unhealthy reliance on external measures to validate his merit. Neither characteristic is at all representative of gnomes, be they real or imagined, for gnomes are quite secure in their subterranean roles. Certainly they rightly fear the beasts of the deep earth, but they do not suffer the anxieties of self-worth known so commonly to man. Nor, further, do they rely on comparison between themselves and ancestral gnomes to judge the virtue of their activities. Rather, gnomes possess an intrinsic, almost obsessive, sense, which compels them to pursue standards of excellence, whether it be in the craftsmanship of their dwellings or the scholarship within their tomes.

Distinct from their surface cousins who meddled in (and thus were weakened by) affairs of men, deep gnomes were a people for whom the light of the sun existed only as an unpleasant rumor, much in the way that the rumor of Hell persists among men, though they often choose not to dwell on it.

It may be argued that mushrooms are more akin to surface gnomes, dwelling as they do in the shallows, interacting in an inextricable manner with the ecosystems of the surface, even emerging after rainfall into sunlight to expose their fruiting bodies. By this logic, Poison Pie must therefore have hailed from a line of deep mushrooms, for he provided no benefit to denizens of the surface world, be they flora or fauna, and he made it a strict policy never to expose his fruiting body.

Being of dubious existence himself, Poison Pie was familiar with these finer points of gnomesmanship. It was this understanding that compelled him to embark on the journey to the vast gnome capital, miles below the surface world and many miles distant. On the outskirts of that city, he knew to find a pair of gnomes, outcasts like himself, whose proximity to civilization was tolerated by the metropolitan authorities due to both a combination of their unique skills and the city’s misplaced pity. Indeed, it is no easy task to survive alone in the subterranean darkness, a veritable wasteland no less than a parched desert or a frozen tundra. Without light, food was scarce. Even water, free of caustic mineral impurities, was difficult to come by at those depths. And, the predators, though rare, were savage.

Poison Pie chose to embark on a journey in which he would endure these hardships because deep gnomes, surrounded by miles of rock in every direction, were experts without equal in the elemental study of stone and, there was one stone in particular that weighed heavy on Poison Pie.

|

|

|

|

|

January 19, 2014

Poison Pie’s journey to the deeps of the Earth was less eventful than it would have been for other travelers. A Man of the Mushroom People has certain innate advantages. First and foremost among them is that, even among omnivores, many fungi are known to be toxic or, at the very least, unpalatable. Therefore, caution is invoked when dealing with unknown species of fungus. Poison Pie, though he had never in the entirety of his long existence suffered the application of the adjective exotic, was an uncommon species, previously unencountered by the creatures that roamed the deep wastelands in search of sustenance. He had only to stand still, cease breathing, slow his heart rate and lower his blood pressure to the slightest of murmurs from which no vibration would be transmitted to the surrounding rock and the passing creatures, reliant on their sensitive antennae, tentacles, paws or feelers of other sorts, were oblivious to his presence. Those few predators relying on sight in the darkness saw only a tall, stiff, leathery and swarthy mushroom and found it no more appetizing than had the parson above.

Indeed, being a Man of the Mushroom people had many advantages that are little promulgated in the circles of scholarly men. This ambiguity in his nature was a source of some small pride for Poison Pie.

|

|

|

|

|

January 19, 2014

“Hebeloma,” said her twin brother from his study, “There is a mushroom standing outside the front door.”

“I know.” She had seen the hulking creature the day before yesterday. “It has business with us,” she called over her shoulder as she headed down the stone stairs to her laboratory, out of ear shot.

Crustuliniforme sighed, closed the book he was reading, set it on the desk, rose and peered through the peephole in the front door to confirm that the mushroom remained, before descending to his sister’s laboratory. The room, surrounded entirely by walls of stone, pocked with several smaller passages leading to storerooms and other dead-ends with purposes unclear to Crustuliniforme, reeked of the corruption of stone. In this lab, his sister practiced and honed a particularly gnomish variety of elemental sorcery centered, of course, on the element of earth. The injection of various chemicals into specimens from her elaborate collection of minerals guided her investigation of the arcane secrets of the deep Earth. This was not the path Crustuliniforme had chosen and he did not often enter his sister’s lab.

He found her, not at work, but standing idly beside a small, mechanical ball mill, waiting for him. “Say what you have to say.” Hebeloma spoke crisply. When I start the ball mill, I won’t be able to hear you. Living with Hebeloma, Crustuliniforme knew well the dull roar of many of her devices.

“There is a mushroom standing outside the front door,” he repeated.

“I know.” Hebeloma folded her arms across her chest, a sign surely of impatience.

“Why isn’t it knocking?” Crustuliniforme asked, as if it should have been the most natural thing in the world for a giant mushroom to stroll up to their front door, which in fact saw very few visitors, and knock.

“It’s of two minds,” Hebeloma answered. She began to turn the crank of the ball mill, ending the conversation.

Crustuliniforme returned to his study. He too, like virtually all deep gnomes, had a special connection to the element of earth. In the majority of their people, this connection manifested as a set of natural abilities: identifying stone, a particular knack at locating veins of ores and caches of minerals, blending in with stone when the need arose, unerringly finding one’s way in the often indistinguishable passes of the deeps. Few deep gnomes ever left the proximity of the city, going no further than the mining operations dictated.

Their parents had been the exception, working as emissaries to other creatures far and wide allied with the interests of stone. Thus, through-out their up-bringing, Crustuliniforme and his sister had experienced a variety of intellectual stimuli not available to their peers. Although the telling of their tale is long, the description of the final result can be stated with brevity: because of their exposure to peoples and powers deemed unnatural, brother and sister were outcasts, judged too different, too dangerous to remain within the city. Here, in an isolated pocket of caves, they were tolerated. In truth, it was a mutually satisfactory arrangement for Hebeloma’s corruption of stone would have subjected her to worse than banishment had the extent of her work ever been made public. Crustuliniforme, for his part, had already been excommunicated from the gnomish monastery, for pursuing trains of thought, long ago prohibited to both scholars and priests of the deep gnomes. So be it.

Returning to his study, Crustuliniforme casually set both hands against the solid stone wall and pulled forth a malleable chunk, as if it were putty. With deft, familiar actions, he formed it into a little gnome-shape, setting it on the floor before him when he had finished.

The creature twitched and blinked open its eyes. The stone smiled ambiguously at this rare opportunity of mobility. Crustuliniforme ordered the gnomunculus, as it was known, to venture outside and poke the mushroom until it knocked at the door.

Almost gleefully, the miniature golem dove into the stone wall, as if it were a vertical pool of water, disappearing, albeit without a splash, to carry out the druid’s command.

|

|

|

|

|

January 23, 2014

Crustuliniforme eyed the mushroom man standing almost forlornly in their receiving room, bent over beneath the gnome-sized ceiling. His sister maintained a cool demeanor, standing in the shadows at the back of the room. What light there was in the room emanated from a pastel purple bioluminescent film growing along the upper walls of the room. After entering the mushroom man had begun by describing that he had been motivated to visit them again based on their past interactions. With a quick glance, Crustuliniforme had confirmed with Hebeloma that neither of them had any recollection of a Mr. P. Pie, Man of the Mushroom People.

This was the first indication that a process in which all traces of Poison Pie’s existence were to be erased from the living world, had already begun. Fittingly, the moment passed right by him and left him none the wiser.

Stuck in their living room, Poison Pie had no alternative but to continue, despite the obvious setback presented by their lack of recognition. “I have brought a stone,” he said weakly, “which I’d like to have examined.”

“I smell it on you,” said Crustuliniforme. It is true that deep gnomes have a nose for minerals and veins of ore, but smelling a stone on a creature that exuded an also transcendental reek of fungal decay stretches the limits of belief. Nevertheless, Poison Pie unfurled his gigantic mitt and revealed the pink marble heart within.

It took all of Hebeloma’s concentration to stifle a gasp, for the stone shone with an otherworldly radiance in a range of the spectrum visible only to those peoples who have dwelt for generations untold in the bowels of the Earth.

Crustuliniforme too barely managed to hide his surprise. He examined the mushroom man’s face and saw no hint of understanding and, more importantly, no sign of deceit; this creature could not see the stone as the gnomes saw it. Gingerly Crustuliniforme approached Poison Pie’s out-stretched arm and carefully lifted the stone, deliberately not making contact with the spongy mitts.

“It’s a heart,” said Poison Pie.

Crustuliniforme did not reply. After examining it in silence, rolling it over in his hands, for several minutes, he walked back to where his sister stood and, almost reluctantly, gave it to her. While she in turn studied the stone, Crustuliniforme returned his attention to the mushroom man.

“You claim to have met us before?”

“I must not have left much of an impression,” mumbled Poison Pie apologetically.

“It’s hard to believe,” said the gnome. “that we have no recollection of you. You are rather...memorable.”

The compliment, if it was one, cheered Poison Pie not in the least.

Without explaining the route by which his thoughts traveled, Crustuliniforme asked, “How did you come by the stone?”

“Beats me,” Poison Pie readily admitted. “There was a boy, then a parson, then an aspect from beyond the stars bombarded my host and...would you believe it?...the upshot of it all is that the church spat out this stone wrapped in a fancy parcel, where it landed at my feet. I took it home and opened it. Then I brought it here.”

After taking a moment to digest this reply, Crustuliniforme said, “It emanates an arcane energy.” By this statement, he hoped to prompt a more coherent explanation from the mushroom man.

“Yeah,” Poison Pie agreed. “I got a feel for that myself.”

Additional questioning convinced the siblings that Poison Pie possessed no further information about the mysterious pink marble heart. They clearly established that the parcel had no return addressee. It was only through repeated interrogation that they stumbled upon the existence of the letter.

“Why didn’t you mention the letter earlier?” asked Crustuliniforme, more perplexed than irritated. “A thing like this,” he pointed to the stone, still held by his sister, “should come with instructions.”

Poison Pie frowned. The expression on his already fearsome face caused Crustuliniforme to take a step backward.

“The letter came before the package,” he said, prefacing what was to follow. It took no small amount of cajoling to get Poison Pie to admit that he had in fact eaten the letter.

Neither brother nor sister asked the obvious question, “Why did you eat the letter?” because the answer was equally obvious. This mushroom man existed in a world not governed by reason.

“You didn’t perchance read the letter before you ate it?” Crustuliniforme asked, though he knew the question to be hopeless.

Poison Pie for his part did not answer, hoping to avoid altogether any mention of his illiteracy, or any other of his numerous shortcomings for that matter.

“Have you had a bowel movement since you ate the letter?” Hebeloma asked. It was the first words she had directed at the Poison Pie and he did not like them in the least. Like many organisms, humans included, he preferred to keep information regarding biological processes on a confidential basis.

In the long pause that followed, before it was clear that Poison Pie would not respond, Crustuliniforme raised an eyebrow and uttered a single word, “Scatomancy.” He turned to his sister. “Indeed, we might be able to extract the contents of the letter from his excrement.” He described the procedure with the enthusiasm of a scientist discussing a novel experiment, without any consideration for the feelings of Poison Pie, and rightly so, for whoever heard of a mushroom having feelings?

“Well, have you?” Hebeloma asked again.

“If you have, you could collect them and bring them here,” Crustuliniforme added, helpfully.

Poison Pie shook his head. These gnomes knew little of mushroom physiology.

“In that case,” said Hebeloma, “There’s always the entrails.”

“Of course,” Crustuliniforme shouted, growing more excited by the minute. “Anthropomancy,” he paused, examining Poison Pie, “or should we call it haruspicy?” It wasn’t clear whether Poison Pie was better categorized as man or animal. “Mycomancy!” he shouted. Inventing a new word always excited the gnome.

“Do you have innards?” asked Hebeloma.

“Of the most caliginous sort,” Poison Pie, who had grown more nervous as the discussion had proceeded, assured the gnome. “Impenetrable to divination of any kind.”

“Challenges are made to be overcome,” Crustuliniforme said jovially.

“I’d rather not,” pleaded Poison Pie. “I like my innards where they are.”

“Don’t be such a baby,” said the gnome, casually waving aside the words of protest. “We’ll put them back when we are done.”

“Wait, brother,” said the sorceress. “It may not be necessary. A magic this powerful may emerge of its own accord.”

The gnomes shuffled out of the room, leaving Poison Pie alone in the soft light. “Don’t be a baby?” Poison Pie softly repeated to himself. He thought that very poor advice indeed. Everyone loves babies. All individuals remotely aligned with the Forces of Good stand united in their protection of babies. Babies are universally adored. There was, to Poison Pie’s thinking, no greater calling than aspiring to babyhood.

His thoughts were interrupted when the gnomes returned, each bearing a torch. Poison Pie momentarily feared they had decided on divination through ashes, but it quickly became clear that they wanted the additional light to examine him by.

He stood stock still, as they circled around him like two dancing vultures. Periodically, they darted close to him.

“Lower,” ordered the sister.

Poison Pie obediently crouched.

“Here it is!” shrieked the brother, now in a state of scientific delirium.

Poison Pie looked down at the spot on the outside of his right bicep that so interested the gnome. Soon all three were studying the area intently.

“It’s coming up,” said the gnome, “from under the skin. Magic of this caliber cannot be suppressed.”

Under close observation, Poison Pie found faint ochre-colored splotches in his swarthy skin. He had not noticed them before. A very active imagination, an attribute that Poison Pie did not possess, was required to assemble the splotches into letters.

“It’s hard to read,” Crustuliniforme told him, “But it will develop with time.”

Poison Pie took no comfort in this diagnosis. Never before had an act of destruction come back to haunt him so personally. Perhaps it could be washed off. Although he, on principle, abstained from bathing, he considered making an exception in this case.

“Even now,” said the sister, her nose less than an inch from Poison Pie’s arm, “there is enough to see it is not a script known to us.” She seemed to encounter something that disturbed her for abruptly she jerked back and announced, “Out of the house! We cannot help you.”

Poison Pie rose slowly to as much of his full height as the low ceiling would accommodate. He had not expected it to end this way. Nor apparently had Crustuliniforme. “What?” the gnome shouted at his sister. “This,” he pointed at Poison Pie’s midsection, “This is interesting.”

Hebeloma tossed Poison Pie the pink stone. It sailed through the dim air and landed with a squishy sound in his palm. “Out,” she ordered again.

“Why?” pleaded the brother.

“Later,” she snapped at him.

Realizing that he had no power to prevent Poison Pie’s expulsion, Crustuliniforme shouted at mushroom man, as he shuffled backward to the door, “It’s a sign. It’s imperative that you heed it. Find out who sent it to you. Seek them out!”

Now hunched in the doorway, Poison Pie shrugged.

“Wear it around your neck,” shouted the gnome, who had now been pushed behind his sister.

“It’s too big,” said Poison Pie, who looked down at the heart in his hand and found that it was now, most inconveniently, the size of a pecan shell, perfect for hanging around the neck. He raised his gaze to the gnomes now backing away from him. “There’s nothing to hang it by,” he said in a tone bordering on panic. He looked down again to find that the pecan-sized heart was now wrapped in an ornate, fine, silver filigree, which came together at the top in a small hoop.

“Around your neck,” Crustuliniforme repeated. “Or better yet, inside...”

An invisible breath pushed Poison Pie back a step and the door slammed shut of its own accord, cutting off the gnome’s final words.

The visit had not turned out as Poison Pie had anticipated, though he had in truth anticipated very little. It was a great source of satisfaction to him that he possessed not the slightest talent for prediction, since the element of surprise was, in his opinion, the single most redeeming aspect of existence.

|

|

|

|

|

January 27, 2014

As a palpable symptom of the decline of the kingdom, even the main roads were subject to brigands. Bands of outlaws would gather under a tough or charismatic leader and prey on travelers until the number of incidents could no longer be ignored by the central government and militia were sent to disperse the brigands. And disperse them they did, into the wilds, where months later the survivors would gradually re-gather at a different location along the highway.

Some bands of brigands were human, some were not, and a few were composed of mixed species. The most vicious outlaws seemed invariably to be human, not because the atrocities they visited upon their victims were any greater than that of goblins or kobolds, but because in humans one chose violence over civilization, whereas in the lesser races, violence permeated all aspects of their society.

In the chill of the early morning light, rising over the mountains to the East, Poison Pie observed that these brigands were not human. They were a breed of dog-men, humanoids with canine characteristics—not werewolves, not afflicted by any ailment of the moon, just dog-men, ugly, vicious in hunger, threatening by necessity. They posed no threat to Poison Pie, however, not because he possessed some invulnerability to all things dog, but rather because they were, to a dog-man, dead, dozens slaughtered by a mighty force that had clearly over-powered them. Bodies were strewn in the road, cleaved in half, some through the middle, some length-wise, and others at various haphazard angles between. It was, Poison Pie, observed a rather gruesome scene. He noted that the trail of carnage led off the road and up the incline into the surrounding forest.

Poison Pie, though possessed of no great imagination, could easily reconstruct the events that led to this slaughter. The dog-men had spotted what they believed to be easy prey upon the highway. They launched their ambush, only to discover that their judgment of the defensive capabilities of their intended victims had been drastically wrong. Once the error was abundantly realized in the blood of their company, they fled for the woods. They had not counted on the blood-thirsty nature of their quarry. Whoever they were had pursued the dog-men into the woods, slaughtering all the way. Perhaps, even now, the slaughter continued, for the corpses were not yet cold. Perhaps, the travelers had been led all the way back to the den where the women and the children were sheltered. Perhaps, a wholesale annihilation of a tribe of dog-men took place at this very moment. Perhaps, Poison Pie thought to himself, there was more to fear along this highway than dog-men. He decided to continue before the travelers returned to the highway to resume their journey.

As he wound his way through body parts on the stone road, he abruptly discovered that one of the creatures on the road wasn’t a dog-man and wasn’t dead. It was hunched in a tight ball, over some remains of dog-man. After a quick inspection, Poison Pie realized it was eating, raw dog leg.

The creature rotated an inhuman head to nearly a reverse position and peered over its back at Poison Pie. With a dismissive glance, it returned its attention to its meal.

It appeared to Poison Pie to be some kind of insect man, a species with whom he was utterly unfamiliar. On two spindly, yellowish legs it crouched. With two of its four arms it rotated meat upon a bone in front of its mandibles. In each of its two lower arms it held a kind of weapon, a small, domed shield made, it seemed out of tortoise shell, from the rim of which projected a blade. Poison Pie could not decide whether this creature was part of the company that had wreaked such devastation on the dog-men or simply a scavenger lately come upon the scene to take advantage of the bounty that would soon attract crows and vultures.

It was none of his business and Poison Pie decided to make a wide berth about the insect man and continue on his way, but half-way around it, the creature called out to him, “Mushroom man!” The throat was not made for the speech of men and the sounds emerged amidst a series of clicks that rendered the message barely intelligible.

“Insect man,” Poison Pie replied in kind.

“You are welcome to this protein,” said the insect man. “There is more than enough to share.”

Hmm. Poison Pie considered the offer and the most polite way to decline it. “Is it tasty?” he asked.

The insect man paused in his meal long enough to reply, “It tastes terrible. All gristle and sinew.” He resumed his meal without further explanation.

The explanation seemed obvious to Poison Pie, who had lived a long time in this world. All things are hard, yet the body requires nourishment. One must take what one can find. If one can do so without complaint, all the better. Poison Pie chose not to answer, let the insect man riddle out his own explanation. Poison Pie turned his attention back to the road in front of him, but was stalled again by a clicking call from the insect man.

“Wait,” it said. “We have come from opposite directions of this road. There may be mutual benefit in an exchange of information.”

Poison Pie allowed his gaze to survey the carnage again. “I should rather not be here when the parties responsible for this slaughter return.”

The insect man gave a knowing nod and emitted a sound that Poison Pie suspected might be laughter. Abruptly, the body uncoiled from the crouch and rose to a height of nearly seven feet, before partially hunching back over to a steady stance. The whole assemblage was composed of spindly limbs and compact torso. His two black insect eyes swiveled ever so slightly and took in the scene. “I know those responsible for this violence,” he said. “They will not subject you to such a fate.”

So, although Poison Pie, could not clearly perceive an advantage in sharing information with the insect man, he did so nevertheless, mostly because the world presented itself as a perpetual maze to him and trying to govern his actions through thoughts of what might be in his benefit usually led him astray.

It began with an exchange of names—Poison Pie for Tchict’Ict, something Poison Pie only vaguely imitated, though his poor pronunciation drew no comment from the insect man.

“What are you?” asked the insect man.

“A man of the Mushroom People. And you?”

“My people have a name for ourselves that others cannot manage. I could relay the names that other, mammalian species have given us, but they are not complimentary. Therefore, I shall say only as you have said, ‘I am a man of the Insect People.’”

“Who are your companions that smote this ruin?”

Tchict’Ict waved off the question. “I do not speak for them.”

As Poison Pie explained the lay of the land along the road behind him, the distance of towns, and the disposition within toward non-human species, two warriors emerged from the woods and wearily strode down the incline back to the road. Each had a sack of what seemed to be the fortunes of war slung over their back. The smaller one held a great axe in his free hand. The larger had a great two-handed sword, six-feet long from tip of the hilt to tip of the blade, in a scabbard strapped to his back. They were covered in the blood of dog-men.

The discussion on the road ceased as the pair approached.

Poison Pie examined the new arrivals, just as they scrutinized him. Both were clearly half-breeds. Humans in their insatiable desires, coupled with just about any species for which such an act was physically possible and their kaleidoscope of progeny were scattered about the kingdom. Here it appeared Poison Pie was confronted first by the mixing of a dwarf and a human. It was closer to human height than that of a dwarf but its stocky build and facial features were all dwarf, a huge beard, a shaved head, a skull carved out of boulder. Its companion seemed to hail from a line that drew its ancestry from both humans and giants. It stood even taller than the insect man and made the enormous sword on his back seem like a child’s plaything. It wore a vest, beneath which the gargantuan chest and arms were covered in purplish-black tattoos of a design unknown to Poison Pie. It made him momentarily recall his own slowly emerging tattoos, for which he had not yet found a remedy. This half-giant had a long mane of black hair. Beneath the caked blood, the bodies of both warriors were covered with old scars. There could be no mistake that these two were long experienced fighters. An unlikely pair, thought Poison Pie, for even he, in his ignorance of social conventions, knew of the ancestral hatred between dwarves and giants and knew that even in beings with diluted blood such animosity was, in general, hereditary. What united this pair was a countenance that unmistakably offered death-dealing at the slightest provocation. The premonition of violence hung upon them like an unseen crown or mantle. Only lives born and raised in ceaseless brutality could account for such a result.

The warriors, it seemed, preferred not to talk until they had gathered the corpses of the fallen and piled them alongside the road to which they set fire. It appeared there had been good reason for Tchict’Ict to eat hurriedly, for they left none of the meat outside the fire for their companion. This task took some time owing to the number of the dead and the scattering of their bodies.

Poison Pie, usually one to help out in a common cause, refrained from aiding the process, instead standing beside Tchict’Ict and silently observing. “A waste of protein,” Tchict’Ict whispered to him.

“It’s a bizarre mammalian conceit,” Poison Pie replied in a similarly low tone. “It’s a burnt offering to the Great Uncaring Ones Who Dwell Above The Stars.”

“No,” said the insect man. “Not even that. These two are godless.”

When the work was done, Tchict’Ict served as an unlikely host for an impromptu fire-side meeting. Again, names without history were exchanged. “Freemul” was attached to the smaller fighter and “Freegolth” to the larger. Poison Pie understood from their surnames that they were escaped slaves. Slavery wasn’t common in this land; these travelers had fled, in all likelihood intentionally, far from home. They had perhaps escaped any pursuit that might seek to re-enslave them physically, but clearly they had not escaped the savagery of their history.

Poison Pie repeated most of what he had already explained to Tchict’Ict regarding the road ahead. “Mostly human settlements,” he told them. “You,” he said pointing to the half-dwarf, “will be tolerated if you have skills at the forge. You,” he said pointing to the half-giant, “will be perceived as a threat and will be allowed entrance only if you have money for the guards at the gate and the authorities within.” Finally, Poison Pie turned to the insect man. “You,” he said with a shake of his head, “had better stay out of towns altogether. Although your kind is unknown here, you will not be given the benefit of the doubt.”

“And what of you?” asked Tchict’Ict, “How does one such as you fare in these town?”

“Poorly,” Poison Pie admitted. He accepted that the treatment he received in human towns was not one of open hostility largely because of the ambiguity associated with his nature.

As the afternoon drew on, Poison Pie allowed them to describe the road by which they had come. It seemed a fair thing to do, a balanced exchange of information, though Poison Pie truly had no interest in knowing elements of what were clearly an unknowable future. Little of what they said registered with him.

The discussion lasted until dusk, for the days were still short, at which time the two warriors started another, smaller fire to ward off the approaching cold. They withdrew edible provisions from the sacks they had taken from the lair of the dog-men. Tchict’Ict did not eat what they offered. When Poison Pie suggested that perhaps they move their camp away from the ambush point, for fear of a second, stronger nocturnal attack, the half-dwarf called Freemul spit in the fire and simply answered, “No.” Such a possibility did not exist. It seemed, as Poison Pie had earlier imagined, that the eradication of the dog-men, man, woman and child, was complete.

Under a canopy of stars, the previously business-like talk expanded to other topics. The three travelers stated without detail that they were indeed very far from home. They were not at all familiar with the customs and inhabitants of this land. It seemed men of the Mushroom People were also unknown to them. When the half-giant Freegolth noted without judgment that, in some respects, Poison Pie looked simply like a sick, malformed human, Poison Pie did not correct him. As has been noted, he encouraged ambiguity, especially in regards to his person and history.

Poison Pie did not ask the travelers about their history. Of the two escaped slaves, they could likely recount only violence, hardship and tragedy, topics which were not suited for such a clear night as had settled around them. With the past out of the question, Poison Pie could ask of their destination, but Poison Pie maintained an uneasy relationship with the future. Still, given a choice between the past and future, Poison Pie’s mitts were tied. “Where are you headed?” he asked.

“We seek peace,” said Freemul. “A quiet life.”

It took conscious effort for Poison Pie to maintain an expressionless face at that unlikely declaration, since the cloud of violence that hung about the two fighters was not one he thought they would ever escape.

“We seek only freedom,” Freegolth added.

“Well, good luck to you,” Poison Pie said honestly, keeping his doubts to himself.

All eyes then turned to Tchict’Ict. It became clear that his history with his companions did not extend back as far as that shared by the two warriors. “I don’t know where I am headed,” admitted the insect man. There are differences between our kinds. “I previously had an assigned purpose associated with my colony. Through an exercise of poor judgment, I was absent on the day my colony was massacred in an inter-colony raid; consequently I did not fall defending it as I should have. My protein was not harvested to strengthen the conquering colony, as it should have been. Since then I have wandered, uncertain whether I can discover an alternative purpose to replace my original purpose.” Silence followed. Innumerable stars shone overhead. Some were grouped into man-made assemblages of constellations. The light of others, too distant, were unseen by terrestrial eyes.

“You are my kind of bug!” Poison Pie exclaimed belatedly. He too felt a profound ambivalence toward the competition between biological and meta-physical purposes.

“You should come with me.” The offer was out of his mouth before he had time to consider it.

“And where are you going?” asked Tchict’Ict.

At this point, Poison Pie felt obliged to relate the tale of the pink marble heart, which now hung from a leather thong around his neck. He pulled it out and passed it around. It seemed a rather insignificant object in the firelight—a bit of cold stone, wrapped in silver wire, something not worth getting so worked up about. In order to convince these three of the impact the stone had had on him, Poison Pie felt compelled to relate the entirety of the story of its arrival and his visit to the deep gnomes in detail. Even when his story was done, there was the sense, shared by all four of them, that Poison Pie had done a rather poor job in conveying any importance of this stone.

“It’s just a stone,” said Freemul. “If you don’t like it, get rid of it.”

Poison Pie agreed entirely with the practical sentiment. Why hadn’t he gotten rid of it? Perhaps, it wasn’t too late to throw it away now. Why had he embarked on some cockamamie journey to find the stone’s rightful owner, when it was just a piece of pink marble?

In some portion of Poison Pie’s brain associated with a poorly defined sensory organ, Poison Pie could sense the energy of the stone. He couldn’t see it as the gnomes had, but he knew something was there and it held an allure for him that he could not shake. Of course, it could also be argued that Poison Pie’s growing infatuation with the stone was simply a consequence of his limited imagination. Regardless, the power of the stone was unable to penetrate the cloak of violence that hung over Freemul and Freegolth. The damage that had been done to them was too severe to ever be repaired. No input of energy could redeem them. They were doomed and they knew it; everyone at the fireside knew it. Such a history as theirs could not be forgotten. Indeed, their best hope, if not to soon meet a martial end against insurmountable odds, was to find isolation where their violence could be contained, where it would not spread to others and engender further violence. Thus, their inability to perceive the stone as it was could be excused.

An insect mind is not like a mammalian mind or even the ambiguous organ that suffices as the mind of a mushroom man. An insect mind is, without shame, governed by biochemical processes to an extent which humans find uncomfortable. Still, Tchict’Ict understood the differences in the futures of his companions on this night—one was a path of ambiguity and the other a fated certainty. As his companions slept, he remained in a restful but alert trance considering a choice between possibilities that his brain had never been intended to make.

|

|

|

|

|

January 31, 2014

In the trance that insects substitute for sleep, where both blood and thought move like molasses, Tchict’Ict was visited by a representative of the Insect Gods. Both parties suffered no small astonishment for neither had ever conceived of the notion that the other might exist.

“A highly improbable, coordinated malfunction of the neural synapses,” Tchict’Ict appraised the visitor aloud.

“An implausible outcome of an evolutionary process gone utterly awry,” said the visitor of Tchict’Ict.

“To hallucinate in this manner, my physiological equilibrium must have been perturbed by an external agent,” said Tchict’Ict.

“To dream of a purpose beyond that provided by biology is absurd,” said the mouthpiece of the Insect Gods, “especially for an insect.”

Tchict’Ict struggled to escape from his trance and release himself from the flow of otherworldly statements that, despite their lack of physical substance, threatened to suffocate him. He steeled his mind, shuttered his eyes, closed all sensory perceptions and willed his legs to straighten. He shot upright, rousing his body and dispelling the vision, just a moment before the visitor was to deliver the message, which lay at the heart of the visit.

Tchict’Ict understood that his decision on the morrow to abandon his ill-fated companions in favor of the company of Poison Pie was influenced disproportionately by this vision, disturbing and inscrutable though it was. What Tchict’Ict could not possibly understand was that the external stimulus that had prompted the hallucinogenic episode in the first place took the form of an emanation of spores from the body of Poison Pie while he slept, a process over which, if pressed on the issue, the mushroom man would deny having any control.

|

|

|

|

|

January 31, 2014

The pair traveled deep through the forests. They had abandoned the road because, having each come from opposite directions, upon consultation they concluded that what they sought lay in neither direction. To most travelers, the forest presented both safety and danger. The dangers did not particularly worry them, as they lay only in the fact that, in the wilds, there was neither civilized law nor municipal guard. Tchict’Ict, who had never known city life, had not benefited from such protection and did not know to miss it. Poison Pie, who had lived on the outskirts of civilization, had known only abuse at its hand and relished the absence of it. The safety of the forest, of course, was the obverse side of the same coin—the opportunity to become lost in an ecological immensity inside of which, even in the case of a most ardent pursuit, they would have been difficult to locate. This safety Tchict’Ict hoped to test, for he desired to escape a second visit from the emissary of the Insect Gods.

The denizens of the forest, floral and faunal alike, observed the unlikely companions. Of insects and mushrooms, they were familiar. The insect man moved as insects do, starting forward, pausing to taste the air for food or threat, before proceeding further. He held a bladed tortoise shell shield in each of his lower arms and a long pole-arm with a wicked, crescent-shaped blade at each end strapped to his back. The mushroom man provided a stark contrast, plodding tirelessly at an even pace, his huge fists swinging in rhythm with his stride. He was apparently unarmed, though every creature of the forest understood that the absence of either obvious armament or camouflage was a manifestation of might. In any case, the travelers were gargantuan relatives of their respective kin dispersed across the forest floor. They would not be lightly waylaid.

“Where are we going?” It was inevitable that Tchict’Ict ask this question once. In his defense, Tchict’Ict came from a place where his biological reflexes, both physical and mental, had dictated his actions. He did not yet fully comprehend the impact of the utter absence of such impulses in Poison Pie.

Poison Pie stopped in the forest. Although the late season had already stripped the leaves from the deciduous trees, enough pine and hemlock populated the forest to provide a canopy, through which the sunlight arrived dimmed and speckled. He looked around him. They followed what was perhaps a deer path, nothing larger used the trail, and certainly nothing bipedal.

“Where are we going?” he repeated in a soft voice. He took a deep breath, as if to begin a lengthy reply, but abruptly exhaled without a sound. He remained silent for so long that Tchict’Ict has already concluded that no answer would be forthcoming.

For Poison Pie, suffused in the living essence of forest, there was every answer to that question; all paths were equally probable, equally valuable. Alternatively, there was no answer, because there was no destination. In between those two asymptotes of thought, there was the simple answer that they sought the original owner of the pink marble heart, which was undoubtedly an incomplete answer and would only diminish the appeal of the prospects before them were such words uttered aloud.

Poison Pie too contemplated refusing to answer, but he did not want to prompt dismay in his new traveling companion, did not want to give him reason so soon to regret his choice. A spoken question deserved a spoken answer, among friends, or those who might one day become friends. Poison Pie opened his mouth again, prepared to say something.

Tchict’Ict observed only the ripples on the surface of Poison Pie’s thoughts. It was sufficient evidence to conclude that his question troubled Poison Pie. “I retract my question,” said Tchict’Ict.

With a word on the tip of his tongue, Poison Pie’s breath fled him. He fixed his companion with a peculiar smile, communicating some combination of gratefulness, bemusement and melancholia, before turning and resuming his way along the path.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This work is made available to the public, free of charge and on an anonymous basis. However, copyright remains with the author. Reproduction and distribution without the publisher's consent is prohibited. Links to the work should be made to the main page of the novel.

|

|

|

|

|

|