|

|

|

|

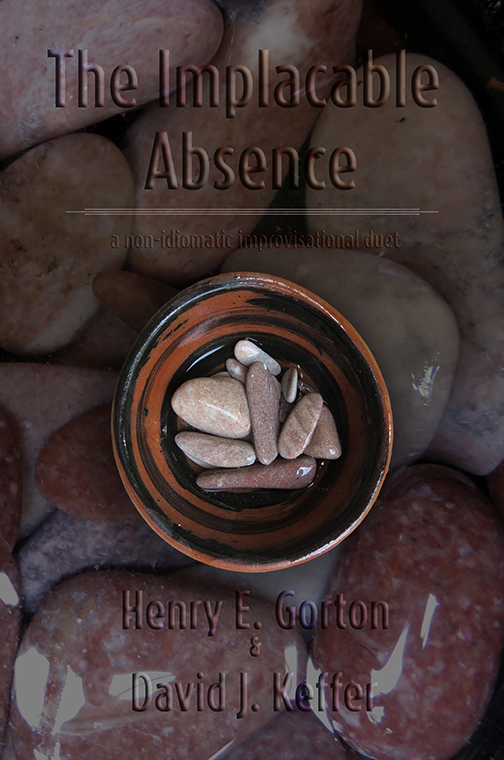

The Poison Pie Publishing House presents:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Implacable Absence

A Non-Idiomatic Improvisational Duet

Henry E. Gorton & David J. Keffer

(link to main page of novel)

February

|

|

|

|

|

February 4, 2014

As they traveled, the skies grew darker, hinting of snow though no flurries had yet appeared. At the same time, the forest too grew darker.

“Dog-men,” Tchict’Ict said to Poison Pie. “I can smell them.”

Indeed, within the afternoon, several dog-men were spotted on distant ridges, spying on them. The pair had traveled too far from the road. Their observers were likely members of another tribe, separate from that which had been slain. Still, their uncharacteristic caution in maintaining a safe distance from the travelers suggested that a survivor or two had escaped the massacre at the road and reported that a single pair of travelers had been responsible for the carnage.

“I suppose they think we did it,” said Poison Pie.

“Better if they do,” said Tchict’Ict. “Then they will let us pass unhindered.”

Although Poison Pie had no desire for the unearned reputation of mass murderer, neither of dogs nor men nor any sort between, he had been thinking along the same lines as Tchict’Ict.

As night fell, the mushroom man and insect man waited for an ambush. The hours passed and the fire dimmed; nothing but the first snow of the winter arrived in their camp, which chilled them but lifted up their spirits. So in the morning they resumed their journey on a thin bed of white-covered leaves. Soon, the dog-men resumed their measured pursuit.

“They are afraid,” Tchict’Ict concluded.

“I would be too,” said Poison Pie, commiserating with the dog-men, “if I thought we were those two escaped gladiators.”

On the next night, contrary to their conjectures, a creature approached the camp in the still of the night. Tchict’Ict roused Poison Pie from a heavy slumber with a firm nudge from his rear appendage.

“Dog-man,” he whispered. “I saw it move a few minutes ago. Now, I only smell it.”

Poison Pie wanted to return to sleep. If the creature remained in the proximity he would not be allowed to do so. Therefore, he bellowed into the chill night air,

“If you are going to come closer, please do so now.” His rough voice thundered through the forest and nearly masked the scurrying footsteps as they fled into the darkness.

Tchict’Ict scrutinized Poison Pie, who eventually shrugged and went back to sleep.

The snowfall began again before dawn, covering the tracks of their pursuer when Tchict’Ict checked for them.

Henceforward, Poison Pie waved a massive mitt when they spotted a dog-man, armed with spear or axe, hiding in a tree in the distance. In this way, another day’s travel passed without incident.

The following night, as they sat around what meager fire they had managed to start with wood dampened by snow, a strange weariness fell over Tchict’Ict. Although his eyes did not close, he fell so deeply into the restful trance that he would have surely been unable to stir his limbs, had he tried. In this comatose state, he watched a diminutive creature, of a kind with whom he was unfamiliar, approach from the shadows of the forest into the flickering light.

Garbed in an ochre robe, she was not a dwarf or a halfling—those creatures he knew. Nor was she a dog-woman. She smelled of earth; certainly she lived in an underground burrow.

She paused in the camp and took careful measure of the insect man, confirming to her satisfaction that he was incapacitated. She approached Poison Pie and withdrew a knife, which she used to cut the leather cord from which the pink marble heart hung around his neck. She then casually, as if this sort of thing were something she did on a routine basis, leaned forward and with all her weight pressed with both hands the stone into Poison Pie’s chest, just above his heart.

The consistency of the flesh of the man of the mushroom people was not as she had expected. It squished as the stone sank into it. There was no blood. Her hands disappeared up to the wrists as she pushed the stone deep into the mushroom man. When she pulled her hands out of his chest, she was rewarded with a spluck! The stone she had left inside. Rising to her feet, she gazed down momentarily at Poison Pie. She gave a quick sideways glance at the insect man, then quickly shuffled off back into the shadows of the forest.

The reverie gradually lifted from Tchict’Ict. He remained inexcusably calm for having just witnessed such an event. Logically, he knew that the inclusion of a foreign body should have a detrimental effect on the well-being of the mushroom man. Still, Poison Pie seemed very peaceful in his sleep as the snow fell and deepened on his blanket. Tchict’Ict chose not to wake him.

When Poison Pie rose of his own accord on the following morning, Tchict’Ict watched him carefully. The insect man could not explain to himself why he did not immediately report the night’s strange event to the mushroom man, but he maintained his silence. He noted to himself that the presence of the mushroom man seemed to be inducing odd behavior.

For his part, Poison Pie seemed not to notice that the weight of the necklace no longer hung around his neck. He did not notice the cut cord off to one side, hidden beneath a layer of new snow. In fact, it wasn’t until nearly noon that Poison Pie realized the necklace was missing. By that time, they had covered many miles and he assumed that the cord has snapped somewhere far behind them. His face filled with a helpless anxiety. After looking futilely at the ground at his feet and the few steps behind them he fixed Tchict’Ict with a sad expression.

Poison Pie said, “Although I never understood the purpose of the stone, now that it is lost, I feel sad all the same.”

Tchict’Ict had every intention then of explaining that he had observed the stone being pressed by a small female of unknown breed into the mushroom man’s squishy chest, but perversely the insect man remained silent. He thought of the mushroom man leading him on a meaningless crusade with some tinge of resentment. ‘Let him have a taste of his own medicine,’ Tchict’Ict thought to himself. He marveled at the thought for he had never in his insect life experienced a sensation such as this. He didn’t even have a word for the feeling, which those of us prone to it would readily recognize as spite.

Beneath the cold, passionless winter sky, Poison Pie let loose with a long, shuddering howl of lamentation. It startled a pair of crows from a nearby ash, who were quick to let their displeasure at being disturbed known.

|

|

|

|

|

February 25, 2014

When Poison Pie considerably slowed their pace, it became clear to Tchict’Ict that he was searching for something. It certainly was not the lost pink heart; Poison Pie was under the clear (though mistaken) impression that they had left that many leagues behind them and, after a period of boisterous self-expression, the mushroom man had assumed a sullen silence on the matter. Rather, it seemed to the insect man that the eyes of Poison Pie from the valleys scanned the contours of the ridges, and from the ridges scanned the narrow crevices leading out of the valleys. It was difficult for Tchict’Ict to make much sense of their surroundings, given the density of the forest around them. Locating any tell-tale geographical feature would have been all but impossible but for the absence of leaves in the trees.

The two travelers had thought that they had left the dog-men behind them, but late that night at camp they heard the same tentative approach of a solitary figure. It waited out of sight beyond the flickering illumination of their fire. When Poison Pie again called for it to show itself or leave them alone, much to their surprise the dog-man slowly strode into their camp.

In fact, it was a dog-woman, no less ugly for her gender. Her muzzle seemed fixed in a permanent sneer characteristic of all her kind. She stopped a dozen feet from the two companions.

Tchict’Ict had stood at the first sight of the creature; he held both shield blades in his lower hands and wielded the pole-arm in his upper hands. For his part, Poison Pie remained seated cross-legged in the warmth of the blaze, returning his gaze to the fire after a cursory inspection of their visitor. One dog-woman posed no threat to them, or so he believed.

Tchict’Ict examined her, trying to determine the motive behind her appearance. Beneath a spartan shirt and pants of a dull gray, which seemed altogether too well kept for a dog, her figure seemed thin, but not emaciated. Hunger had not driven her into their camp. She bore on her back a pack and in her hands held no weapon. She seemed ill-prepared for the possibilities these wild lands presented.

Tchict’Ict naturally expected one of two outcomes—either the dog-woman would provide a reasonable explanation for her visit (the more unlikely of the outcomes) or there would be violence. The surprises that night continued for Poison Pie asked for no explanation and the dog-woman offered no fight. Instead, she tentatively approached the fire, her eyes all the while on the deadly crescent blades of Tchict’Ict. She sat down and raised her front paw-hands to the fire.

Poison Pie looked over at Tchict’Ict. “She’s cold,” he said with a shrug.

Despite the fact that Tchict’Ict could not deny the chill in the night air, it seemed to him somehow an unfair explanation, as if Poison Pie wasn’t sharing all of his information. Tchict’Ict did not yet fully comprehend the extent of Poison Pie’s apathetic relationship with the notions of reason, purpose and the phenomenon of cause and effect. It was too much to ask for Tchict’Ict to adopt the same attitude at so early a juncture in their partnership. “What do you want?” he chittered in an agitated tone at the dog-woman. The hostility in his voice could not be ignored.

The dog-woman crossed her arms in front of her chest and leaned in toward the fire. “Does my appearance upset you?”

“As it should,” said Tchict’Ict. “We are not counted among the allies of the dog-people.”

“They have a name, you know, beyond dog-people.” She rubbed her paws together. “Most people call them gnolls.”

Momentarily ignoring the curious fact that she referred to her own kind as an outsider, Tchict’Ict replied, “Evil by any name, we want no party with dogs. Be gone!” He gestured with his weapon at her.

“In that case...” said the dog-woman, trailing off. Crouched in front of the fire, the dog-woman provided another surprise to the travelers for before their very eyes in the matter of a few seconds, she transformed without any apparent exertion from the shape of the dog to a shrunken woman, clothed in same, now slightly over-sized, dark gray shirt and pants.

This time Poison Pie’s startled reaction dwarfed Tchict’Ict’s own surprise.

“Hebeloma!” Poison Pie shouted, already having risen to his feet.

Although Tchict’Ict did not know the name, he did recognize from the night before the woman who had placed a spell of paralysis on his body and plunged the pink stone into Poison Pie’s chest. He had never observed firsthand the sorcery of shape-changing and his amazement knew no bounds.

“What are you doing here?” Poison Pie asked. He ransacked his mind for reasons the deep gnome sorceress would brave her aversion for the surface world to visit him. It had to have something to do with the stone. “I lost the stone!” he wailed.

Now it was Tchict’Ict’s turn to provide the surprise, for he replied in place of the sorceress. “You haven’t lost it.”

In his confusion, Poison Pie looked from Hebeloma to Tchict’Ict and back, waiting for an explanation.

“This one,” Tchict’Ict said, pointing again with his pole-arm at the woman, “pushed the stone inside you last night.”

The silence in the camp was only disturbed by the popping of the pine in the fire and the sough of the wind through the empty branches, as Poison Pie attempted to make sense of this new revelation and its unlikely source. He wanted to express to the insect man that he did not understand anything about what was going on, not the literal meaning of the words, nor the fact that Tchict’Ict knew of the location of the ostensibly lost stone and had kept silent on the matter, nor least of all any semblance of reason behind the entire situation. At times like these, his utter lack of understanding threatened to overwhelm Poison Pie. His natural response was to have some incarnate portion of his spirit rise out of his body and hover over the scene, observing from a more detached and advantageous point of view that might provide some alternative perspective. He saw only a triangle around the fire, composed of a mushroom man, an insect man and a deep gnome. This sensation of disembodiment lasted only a few moments and transpired without either of the two potential witnesses apparently any the wiser. However, upon the return to his body, Poison Pie understood that one of them was not who they seemed to be. “You are no more Hebeloma, than you are a dog-woman,” he said. “You are a doppelgänger.”

“We prefer the term changeling,” said the gnome who was no longer Hebeloma, though she still looked the part. “There is a distinctly negative connotation associated with doppelgänger.”

Poison Pie was in no mood to debate semantics. He gestured with a mitt toward the changeling in a half-hearted request for some explanation. Eventually, he collapsed back down on the ground and resumed his contemplation of the fire.

It fell to Tchict’Ict, as he began to realize it often would, to make sense of events. He began his interrogation in a calm, patient tone. There were many questions to be answered.

“Why did you take the appearance of a dog-woman?”

“It’s the safest way to travel in the land of dogs,” the changeling replied.

“Why did you change into Hebeloma?”

“Because you said the dog-woman upset you.”

That reply did not exactly suit Tchict’Ict but he suppressed his own reaction in favor of continuing the questioning while answers were so readily forthcoming.

“Why did you push the stone into the mushroom man last night?”

“Oh, that wasn’t me,” said the changeling. “That must have been the real Hebeloma.”

“You saw it?”

“From my vantage point outside the camp, I observed the entire ceremony.”

Ceremony too seemed a strange word to both Poison Pie and Tchict’Ict, but neither commented on it at this time.

“If you are not a dog-woman nor a...whatever this Hebeloma creature is...”

“A gnome,” Poison Pie said helpfully.

“Whatever it is,” Tchict’Ict continued, “then what are you?”

“I am an itinerant monk, nothing more.”

Tchict’Ict was wholly ignorant of the myriad of pantheons of deities that graced this world and he had no knowledge of the nature of the business of monks. “What is it you do?”

“I travel.”

“You are ill-equipped for travel,” said Tchict’Ict, noting the thin fabric of the monk’s clothes.

“I practice austerities,” the monk stated by way of reply.

“To what end does one practice austerities?” said Tchict’Ict, unsure of the term.

“To the only end,” replied the monk, “To cultivate virtue.”

Now on even less certain footing, Tchict’Ict asked, “And what purpose does this virtue serve?”

“The cultivation of virtue serves to accumulate merit,” said the monk.

None of her words made sense on any level to Tchict’Ict and he suspected that the changeling well knew it. Nevertheless, at the point of exasperation he asked, “And what good is a reserve of merit?”

At this question, the monk smiled, “When the physical body dies, in the process of its decomposition it provides nutrients to the soil which allow further life to flourish. When the spirit is released from the body, it distributes its accumulated merit into the ether, providing the energetic sustenance upon which those in pursuit of the further accumulation of virtue exclusively rely.”

“Spoken like a real monk,” said Poison Pie. “I think we can be sure that she has finally come clean with us on who she really is.”

“Then show yourself for who you really are,” demanded Tchict’Ict.

The changeling, in her guise as Hebeloma, smiled again. “A changeling no more reveals her true form than a man of the mushroom people would expose his fruiting body.”

Tchict’Ict glanced at Poison Pie for confirmation. He was met with only an uncomfortable silence from the mushroom man, who did not even approve of the public mention of such topics.

“Why are you here?” asked Tchict’Ict.

“I already told you,” said the monk. “I have been guided here to cultivate virtue in this company.”

Tchict’Ict knew better than to ask who had provided this guidance. “Poison Pie will help you cultivate virtue?” he asked, unable to keep the doubt from his voice.

“Something like that,” said the monk, ambiguously.

|

|

|

|

|

February 26, 2014

Poison Pie was unhappy. His unhappiness was not of the usual, existential variety, in which he moped over the general incomprehensibility of the world and his role within it, so typical of men of the mushroom people. On the contrary, the current happiness of Poison Pie had a very specific, though no more comprehensible, source: a pink stone supposedly now lodged in his chest next to his heart.

He had required both Tchict’Ict and the changeling to provide their individual accounts of the ceremony (as it has been called) in which the pink stone was inserted into him. “For the record,” he noted, “I would like it clearly understood that I did not ask for this.”

“Who would?” agreed Tchict’Ict, who could perceive no benefit in anyone having internalized a stone.

The changeling, still in the form of the deep gnome sorceress, Hebeloma, kept her thoughts to herself. The sun had risen. The winter air was crisp and clear. The sky was a cloud-free intense blue, viewed in jagged fragments above the canopy of limbs and twigs. On such a morning, there seemed little that could perturb the serenity of their situation. The changeling predicted that soon the simple indisputable fact of the morning and the inherent majesty of the world that gave rise to it would raise Poison Pie’s spirits.

As the mushroom man and the insect man had gathered their gear, so too did the changeling. It was clear to all of them that she would join their company, for however long it remained intact. They marched through the snow gathered in the north shadows of each tree and the sodden leaf litter distributed across the forest floor.

If Poison Pie’s spirits rose, he gave no clear indication of it. However, he did change the subject. “What are we to call you?” he asked the changeling.

“How about Hebeloma?” she replied.

“That is way too confusing,” said Poison Pie. “I already know a Hebeloma and I am none too fond of her at the moment.”

“Were you ever fond of her?” asked Tchict’Ict who was trying to piece together the prior history between the mushroom man and the gnome.

Poison Pie sighed. He had been on the verge of answering a certain “Yes!” but during his last visit to the home of the gnome and her brother, neither had shown any recognition of him whatsoever. To be so totally forgotten seemed to undermine any suggestion of friendship between them. In the end, Poison Pie could only mutter,

“I don’t know,” which helped Tchict’Ict not in the least.

“But I do know,” continued Poison Pie, “that you cannot be called Hebeloma. What’s your second choice.”

“Celia,” said the changeling.

“Much better,” Poison Pie agreed. He certainly hadn’t expected things to move so simply to a satisfactory conclusion. “And about your appearance...” he added uncertainly. “Do you have one that better matches Celia?”

“Yes,” said Tchict’Ict, interested in seeing the shape-changing magic again, “Do you have a monk’s look?”

As easily as one might slip on a pair of gloves, the deep gnome sorceress transformed into an old man, clad in the same gray clothes with the same pack on his back. He was the very image of a monk—sandaled feet, skin creased with wrinkles and peppered with age spots, hair a pure white, eyebrows two sizes too large for his diminutive frame. One looked intuitively to his hands to see the bell and bowl by which he would collect alms. One expected nothing but sutras to emerge from his lips. “Does this suit you better?” Celia asked in the high voice of an old man.

“I thought Celia was a woman’s name,” Poison Pie muttered, feeling somewhat embarrassed that he was acting entirely too persnickety on a subject which really was not his concern. All of the sudden he wasn’t even sure that a woman could be a monk; he hadn’t thought of that before.

The insect man too did not like the look of the monk. Tchict’Ict was on cautious terms with religion of any sort and did not relish the prospect of traveling in the company of someone who so clearly looked the role of a holy man. “I liked the gnome better.”

“So be it.” Within a few moments, Celia stood before their eyes, again in the form of Hebeloma. Without another word, the trio continued their march.

Had there been any observers in the hills they would have certainly remarked on the unlikelihood of a mushroom man and an insect man traveling together. The addition of a deep gnome, a member of a race who almost never breached the surface and who under no conditions tolerated the light of the sun, only served to deepen the suspicion that the composition of the trio was so preposterous that it must simply be chalked up as a figment of their over-active imagination.

|

|

|

|

|

February 26, 2014

“The stone was made of pink marble and was carved in the shape of a heart—a four-chambered mammalian heart.” Poison Pie had described this point several times already but Celia insisted that he repeat it.

“You are missing some detail. Think!” she urged him. A little clarity in this matter might shorten the duration of their wandering in these woods, lovely though they were.

There was nothing more to be said about the stone. Poison Pie was again reluctant to reveal that the stone had arrived at about the same time as an explanatory letter, which he had eaten without reading. He had already had to come clean on this account to someone who looked exactly like the form that Celia now donned; he had no intention of doing so again. Nervously, Poison Pie looked down at his skin. The blotches were gradually darkening. It was only due to his swarthy complexion that his companions had not noticed the change coming over him. The real Hebeloma had seen it for what it was and predicted that in time the content of the letter would be revealed.

“The stone heart is inside you,” Celia said, “Listen to it.”

“Listen to my heart?” Poison Pie said dubiously.

“Only the stone one,” Tchict’Ict clarified.

“I think I once heard a song by that title. A bard visited my village. Of course, I wasn’t invited to the performance but I hung back and listened from behind a wagon.” Poison Pie started humming a jaunty tune. As he remembered the details, he said, “The bard played a lute.” Poison Pie began to sing in an off-tune, monstrous, gravelly voice,

Listen to your heart...Baby!

Something something something...Lady!

I forgot the words...Maybe!

Something else happened...with Gravy!

At the end of the brief performance, Poison Pie examined the aghast expressions on the faces of the two members of his audience. If questioned prior to this moment, Poison Pie would have claimed that the inexpressive face of the insect man was incapable of such an emotional display, but evidently this was not the case. By way of apology Poison Pie said, “That’s why I liked going to church. They have books with the words to the songs in them in every pew and, even if you are a bad singer, they let you sing.”

“I wouldn’t have pegged you as a church-going guy,” said Celia.

“That was before the parson banished me,” Poison Pie admitted.

|

|

|

|

|

February 27, 2014

“I’ve been meaning to ask you,” said Poison Pie to Tchict’Ict, “when were you going to get around to telling me about the fact that the stone I had been looking all over for was stuck in my chest?”

“Hmm,” said Tchict’Ict, or so we suppose since the clicking of his mandibles prevented a smooth “Hmm” from emerging. “I hadn’t found the right opportunity yet. It seemed a difficult subject to broach.”

Poison Pie could hardly find fault with that reply.

|

|

|

|

|

February 28, 2014

“What do you mean, you have never meditated?” Celia said, staring in disbelief at the mushroom man. “Not even once in your life?”

Poison Pie shrugged. He had once, long ago, harbored a mild aversion to having other people act like he behaved completely beyond the bounds of civilized society, but he had received so many reactions of this sort in his life that he had become accustomed to them. “There never seemed to be a need...” he muttered.

“A need to find your inner balance? A need to put your existence into perspective?” Celia looked to the insect man for support. “Can you believe this?” she asked him.

Tchict’Ict scratched at the hard chitin on his scalp with the end of a pointed finger. “To be honest,” he said, “I have never meditated either. I don’t even know what the word meditation means.”

Celia took a deep breath. She craned her neck up to the navy blue sky. In the west, there were tinges of pink among the clouds. Although the monastery adhered to the firm practice that dawn proved the optimum hour for reflection, she had always found dusk to bring her best insights. “Set your weapons down,” she said to Tchict’Ict.

“Why?” asked the insect man, though he reluctantly complied.

“Because we are all going to meditate right now,” Celia answered. “And you can’t meditate with weapons in your hands.” She turned to Poison Pie. “Sit,” she ordered.

“It will be dark soon,” he said. “We should build a fire.” He had no desire to meditate, after having so successfully avoided it through-out his whole life thus far.

“We shall meditate in the dark,” Celia insisted.

So, seated in a triangle, they meditated as the sun set and night deepened the chill in the air. They followed each of Celia’s instructions. They closed their eyes. They listened to their inner voices. They listened to and catalogued the night sounds of the forest. They invented new sounds that had never before existed and shared them with each other. Celia expelled a polyphonic resonance from her throat. Tchict’Ict recited a poem in his native insect language, a language which had never known poetry before. It was a poem of rapid clicks and high-frequency chirps. It gave Poison Pie a headache. Poison Pie made a sound like this:

ba-bum BA-BUM ba-bum BA-BUM ba-BA-bum-BUM BA-ba-BUM-bum BA-BUM ba-bum

Of course, it was the sound of two hearts beating at the same time, one louder than the other. The two hearts maintained different rates and their beats were synchronized only infrequently and then by chance.

Celia recognized the conflicting pattern as the beat of the fleshy heart and the stone heart, both lodged within Poison Pie. She did not utter a word for she wanted Poison Pie to experience the effect of a meditation.

Although Poison Pie would never admit it, on the following morning, when he abandoned the meandering path of which their trek through the forest had so far consisted and instead led his companions on a bee line to a mushroom-filled grove, hidden at the end of a ravine, containing the object for which he had been searching, the clarity of his stride had been imparted to him from a message contained in the intermingled beating of the two hearts. On the contrary, Poison Pie attributed their abrupt arrival at the cave entrance to sheer luck.

Celia for her part remained the soul of discretion and did not press him on this fortuitous turn of events.

Tchict’Ict was too agitated to pay attention to these events. He had the unfortunate sensation that the emissary of the Insect God had tried to visit him during their meditative exercise. Since he suspected that the emissary was a hallucination brought on by an imbalance in brain chemistry, he had every intention of avoiding him and was correspondingly vexed at his failure to do so. The hallucination had congratulated him on his willingness to engage in an introspective practice such as meditation. From there on out, Tchict’Ict could not help transfer some distrust, originally aimed at the emissary of the Insect God, to Celia, who had tricked him into meditating.

The mushrooms in this grove were half as high as Celia in her gnome form. “These are the largest mushrooms I have ever seen,” she exclaimed. Aside from their size, there was a remarkable variety. Some had a flat matte and others seemed to gleam with a slimy sheen. The colors ranged from ochres and tans to red caps flecked with bright yellow flakes. Some stalks bore purple rings and others silky skirts. The vibrancy of this grove was wholly out of place compared to the deep winter of the rest of the forest. “This is no ordinary place,” she concluded.

Poison Pie pointed to the cave where the ravine ended in a steep, stone cliff. “No,” he agreed. “There’s a breath that emerges from this cave, which gives life to this growth.”

Tchict’Ict and Celia approached the cave entrance and stopped beside Poison Pie. They both breathed deeply. The air before the mouth of the cave was faintly rank with decay. Celia wrinkled her nose. Tchict’Ict dialed down the sensitivity on his pheromone sensors.

“Say your farewells,” Poison Pie announced to his companions.

“We’re not leaving you,” Celia replied, confused by his words.

“Oh, not to me,” said Poison Pie, ‘to the surface world. We go now to the City of Mushrooms, crawling through the darkness of the deep earth.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This work is made available to the public, free of charge and on an anonymous basis. However, copyright remains with the author. Reproduction and distribution without the publisher's consent is prohibited. Links to the work should be made to the main page of the novel.

|

|

|

|

|

|