|

|

|

|

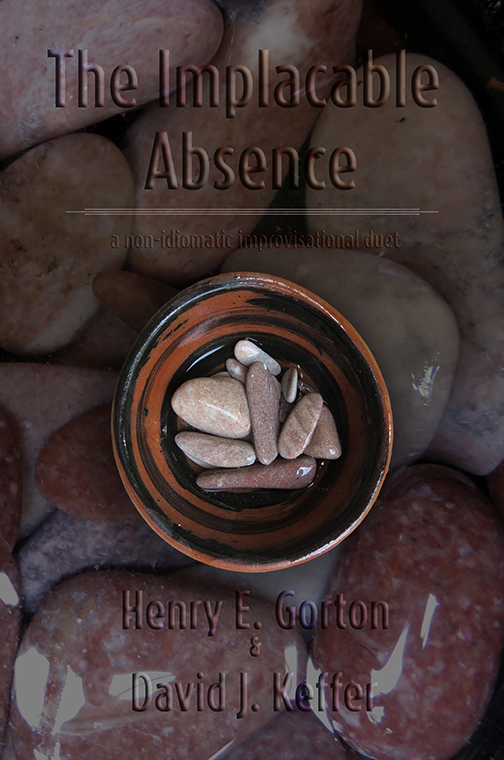

The Poison Pie Publishing House presents:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Implacable Absence

A Non-Idiomatic Improvisational Duet

Henry E. Gorton & David J. Keffer

(link to main page of novel)

April

|

|

|

|

|

April 7, 2014

Assuming a form of another is always a fragmenting experience. A changeling is able to adopt the physical appearance and mimic to great effect those characteristics that are innate to that form. Thus, as a troglodyte, Celia was able to exude the chemical stench, characteristic of the species. The peculiar gait associated with joints of their reptilian legs came no less naturally to her than it did to any other creature so equipped. However, learned capabilities, both physical and mental, were not within the reach of a changeling. As Hebeloma, Celia could not cast the spells of the sorceress. As a troglodyte, Celia could not understand the language. However, as someone who had lived her entire life mimicking others, her ability to pick up on subtle clues and to imitate body language and gesticulations as she observed them was a finely honed skill.

The passage of the quartet through the fungal tunnels eventually led to the outermost troglodyte habitations. The passages widened into broad caverns completely defined on all surfaces by hardened fungal growth. The entirety of the pale illumination emanated from these surfaces. The structure of this city, like all troglodyte cities, located power and wealth at the city center. As one moved radially outward, the political and economic might dwindled precipitously. Thus, those on the outskirts of town were either indigents, crouching in hovels consisting of nothing more than the covering of a mushroom cap, or tenement farmers raising over-sized insect larvae in shallow pools and corrals constructed of dehydrated stalks. As the party marched past these ponds, the air reeked of stress and poverty manifested in the troglodyte pheromones. They did not dare be caught raising their eyes to steal a glimpse at the passage of the high priest and his unusual cohorts. Even Celia, a lowly female, associated as she was with Olm, was too elevated to greet or examine directly.

Presumably a spy of the temple, upon first site of party, raced to the temple to inform the high priest and his court of the unexpected and certainly unwelcome return of former high-priest Proteus Olm. Within a quarter hour, as the party passed these pools and came upon a wholly organic barricade that served as the city walls, they were accosted by a regiment of spear-wielding soldiers. The captain of the guard spoke to Olm in troglodyte, though his message was clear to all. They were to be escorted, under guard, to the judiciary chambers of the temple.

As it turned out, not all of them shared the same destination. Females were not permitted entrance to any portion of the temple, save the rear harem halls. Nor were weapons allowed by commoners or outsiders in the temple. The crescent polearm and shield blades of the insect man looked entirely too lethal to allow within the same chamber as the high priest. Thus Celia and Tchict’Ict were led to a waiting room that upon closer inspection appeared to more resemble a prison cell. The door was closed behind them and no attempt was made to stifle the click of the key as the lock was turned.

Olm and Poison Pie, man of the mushroom people, after a brief farewell and promise to reunite, were led to court to plead their case.

|

|

|

|

|

April 7a, 2014

“By the unending glory of the Deadly Galerina, I, Proteus Olm, devoted servant, bound hand and foot, cast into the lake of Sinonatrix, from which none have returned, was found virtuous in the sight of the Lord Galerina and delivered to safety. My bonds loosened of their own accord, by the will of the Almighty. My passage through those dark waters was hastened by a power beyond my own. Though the snake, Sinonatrix, coursed through the water behind me, ever intent on her prey, still faster was I propelled to the far shore. May all hail the mighty deeds of the Deadly Galerina, who knows no limit in the succor of his faithful.”

Poison Pie, who understood not a word of troglodyte, though he had a suspicion that Sshlumpp meant idiot, felt the speech of Olm before the high-priest and his array of judges and staff, continued for an interminably long time.

“Not yet was Lord Galerina finished bestowing gifts upon his humble servant, for as I huddled amidst the dark stone, a servant was sent unto me, a creature from the fungal domain, demented and powerful in the ways of the Deadly Galerina!”

Poison Pie nodded amiably, as Olm thrust a hand in his direction.

“This creature, yeah, the very one towering before you, knelt before me and swore his life to forward the restoration of the Deadly Galerina’s glory in the City that Crawls, a heavy task that has been set upon my shoulders! Though I am weak, I cannot abandon this task nor abdicate the responsibility that the Lord Galerina bids me undertake.”

Poison Pie observed the nervous shifting behind the row of desks mounted on a platform on three sides of the chamber. It seemed to him an ominous sign.

“Do not doubt that my cause is righteous!” shouted Olm. “Do not doubt the power of the champion sent by the Lord Galerina to clear my way, for in my return to the City that Crawls, I had no choice but to pass again across the Lake of Sinonatrix. That snake coiled at the bank, prepared to spring. And spring she did, but her venom found no purchase in the caliginous innards of this holy beast. With mighty mitts wrapped around her throat, this servant of Lord Galerina, thrashed the sorceress snake against the unyielding stone bank. He cast her like a serpentine bola into the deeps of the waters. Then we crossed the placid lake undisturbed. Henceforth, that lake shall no longer be known as the Lake of Sinonatrix, for the Lord Galerina has claimed it for his own. He allows the snake to remain in the depths, a renter, nothing more, a hired guardian of our doorstep. From that fateful day forward the lake shall be known as the Triumphant Waters of Proteus Olm! So it has been decreed by the Deadly Galerina!”

“And now, by the order of the most holy Deadly Galerina, you are to return to me the scepter of the high priest, that I may set his temple, asunder in heresy and scheming, in order again.”

A general ruckus of dissent broke out among the gathered priests and scribes. Over these protests, Olm continued in a shout, “Those who do not obey the commands of the Deadly Galerina shall be laid waste. Let no troglodyte escape the wrath of his indomitable champion!”

Olm fixed Poison Pie with a fierce glare.

Poison Pie took this as the cue to step forward, intending now to plead his own case, rendered from his own individual perspective. He paused when his first step caused a wild rush for the exits of the chamber.

|

|

|

|

|

April 14, 2014

“What do you think’s going to happen to Poison Pie?” Tchict’Ict asked from a crouching stance imposed by the constraints of their cell.

Celia, still in the form of a troglodyte, cast a rather hideous smile toward the insect man; it was the best that the reptilian face could manage. “What do I think is going to happen?” she repeated softly. A few moments of silence passed, then she repeated the question again in a sort of sing-song voice, emphasizing the natural rhythm of the anapests and iambs. She continued repeating it, maintaining a low volume, as if it were a sutra familiar to her and she intent on entering a trance.

Although Tchict’Ict did not understand her purpose, he found the chant soothing all the same.

Without breaking the chant, Celia leaned over to her pack, for the guards, who, not even stripping Tchict’Ict of his weapons, had thought nothing of a diminutive female and her bundle. From within the pack, Celia withdrew a deck of well-worn fortune-telling cards. The hands of a troglodyte were not able to shuffle the cards in the conventional manner, so she resorted to spreading them out on the fungal surface of the floor and randomizing them as best she could. When she was done, she left the cards where they had come to rest on the confined space between her and the insect man. She had not abandoned her chant nor changed its patient tempo.

Celia closed her eyes. At that same moment, Tchict’Ict had the distinct impression that he had blinked, though such a thing was not possible for an insect man without eyelids. Nevertheless, the world had momentarily gone dark and upon reappearing had presented double images, slightly offset from each other. It took several seconds for Tchict’Ict’s eyes to focus and bring the two disparate images back into one. Several times however, as the chant continued, he had the distinct sensation that the two images were trying to separate themselves again.

Without warning, Celia stopped chanting though she did not open her eyes. “We have found the alternate timeline, in which your question was first asked.”

Tchict’Ict thought it odd, that if Celia were to go to all the trouble of transporting them to an alternate reality, she didn’t choose a future one where the answer to his question was obvious, rather than to some place in the past where his question had first been asked. Regardless, Tchict’Ict readily conceded he was a novice at dimensional traveling, if that indeed was the activity in which they were currently engaged, and left the nuances of the trip to Celia.

Celia flipped over the first card and announced without opening her eyes, “The Marble Heart.”

Tchict’Ict examined the card. If he had been asked to describe it, he would have called it, “The Three of Swords.” He found nothing remotely heart-like in it, though again he was willing to concede that he was no more gifted at augury than he was in trans-dimensional travel.

“The Maker of the marble heart,” Celia explained, following the same tempo as before, “in ages ere the mushroom men did cast a spore beneath the Earth, a seed of city, which from a mote would via stone-wrought eons crawl through caverns and through crevices, expanding and engulfing voids, illuminating in fungal light ornate architecture of decorated caps and sympathetic trunks, tangled mycelia and germinating volva.

“In the foreshadowing of these halls, the maker of the marble heart strode and set to work a means by which the city’s magnificence would call to it a host of caretakers who sheltered within it, tended to its wounds, and manicured its weapons. This crawl of the city outlasted millennia, for it had been created for a purpose and that purpose had not yet revealed itself.”

Abruptly, Celia’s eyes flew open. Tchict’Ict saw a revelation reflected in her eyes but, though he pressed her, she refused to say another word of her vision. To the contrary, the uncertainty in his vision of the world coalesced into a single entity while she gathered the cards into a neat stack, which she deposited back into her pack.

“Only one card?” Tchict’Ict asked, who, having held every expectation of seeing them all overturned and explained, felt extremely dissatisfied with the aborted flow of information.

“There is no time for that now,” Celia chided him. “We must hurry. Events have been set in motion and we do not want to be left behind.”

Tchict’Ict had previously tried to force open the door to their cell. Although it was constructed of some biological material, possessed of a modest degree of elasticity, it had ultimately proven unyielding to the extent of his strength. “Shall I try to cut it?” he asked, bringing the crescent blade to bear.

“It’s not necessary,” Celia replied. “Be ready to run the instant it begins.”

“What begins?” Tchict’Ict asked.

“The paroxysm.” She said the word as if nothing could have been more natural.

“What is a paroxysm?” asked the insect man.

“A kind of sneeze,” Celia explained, keeping her attention focused on the door.

While he knew this other word as a momentary convulsion fit only for mammals, it did not help him better understand what was to come. “What does that mean?” Tchict’Ict asked in a growing mixture of tension and excitement.

“Gorgonio,” she said, though that word too meant nothing to Tchict’Ict, “was an alchemist. He grew this city as a kind of biological reactive vessel. To activate, it requires two things—first, a reagent or substrate and, second, a catalyst.”

Tchict’Ict had a fair idea of the two missing components, although he understood neither their respective roles nor the response they would induce. “The pink marble heart is the catalyst?” he asked.

“Indeed,” said the monk.

Neither needed to identify the reagent, seeing as there was only one obvious candidate for such a role.

|

|

|

|

|

April 15, 2014

In many religions, a divine aspect is imparted to music. Life itself is considered a complex song in which each animate being and inanimate object has a role in a universal orchestra. The appropriate response to such a song is awe, for the song can neither be fully comprehended nor ignored.

Mushrooms sing. Like everything else, the fungal kingdom constitutes a vital component to the living ecosystems that dot the physical world. Their leadership role in the unheralded processes of decomposition takes the form, not of a dirge as one might expect of a process associated with death, but of a hymn, a hymn of praise that revitalizes the Earth, converting that which is no longer useful to nutrients providing sustenance for the life to come.

The sonorous choir of mushrooms is not widely appreciated, beyond trees who largely keep their opinions to themselves. Few others press their ear to the ground and listen to the reverberations of the strings of mycelia transmitted through the soil. Luckily, mushrooms do not perform this music for the purposes of receiving adoration from an appreciative audience. No, mushrooms sing only because, (the reader may choose the following that best suits their life views) (a) that is the function by which they best survive, bred into them through millions of years of evolution, (b) that is the way the good Lord made them and who are they to silence the voices so given, or (c) both of the above.

|

|

|

|

|

April 18, 2014

Poison Pie, Man of the Mushroom People, was surrounded by a hundred troglodytes, each brandishing a spear, glistening with a toxin, whose production was known only to certain elders of the tribe that dwelt within the City that Crawls. Beside him, Proteus Olm, former high priest of the Temple of the Deadly Galerina in the City that Crawls managed a delicate balancing act between bravado and cowardice, which manifested largely by him poking his head out from his position behind Poison Pie.

“You are a servant of the Deadly Galerina,” the old priest hissed at Poison Pie. “Dispense with my enemies!”

Poison Pie momentarily glanced down at the troglodyte then back out at the host of spears. He was unable to conceive of the action or sequence of actions, which Olm wished him to perform. Almost bashfully, he whispered back at Olm, “What did you have in mind?”

“You are a Champion of the Deadly Galerina. Use your powers.”

Poison Pie found the unquestioning belief in the priest’s voice both complimentary and disheartening. “My powers,” he repeated quietly. He tried to remember just exactly what his powers were. “What am I best at?” he asked himself silently. Poison Pie remembered that he was really good at being a mushroom man, exceedingly good in fact. Mushrooms accepted failure with no less equanimity than they did success, perhaps more. He could, perhaps, simply accept whatever fate befell them at the hands of the judges and their spear-wielders, though he suspected (and rightfully so) that this was not what Olm had in mind.

Poison Pie was also quite competent at adjusting his philosophical perception and expectation of the universe to accord with the circumstances in which he found himself. This fluidity in expectations came in extraordinarily handy when one was perpetually beset by failure and one did not desire to be overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy or defeat. This seemed, at the moment, the proper path to Poison Pie. He raised his arms slowly so as not to provoke any rash thrusts of the spears.

The front row of soldiers took a half step back in trepidation for they feared the wrath, promised by Olm, of this strange creature, half-humanoid and half-fungus.

“Friends,” said Poison Pie in a language they could comprehend but a few words. “I am Poison Pie.” Poison, it turned out, was one of the few words with which troglodytes were familiar, as they were masters of blending poisons and traded them with merchants of species in many tongues.

Before Poison Pie could finish the incantation that the troglodytes believed would subject them to the lethal and most excruciating poisons of the Deadly Galerina, he was covered in a heavy net, spun from thick fibers, with Olm trapped against his side.

“Break through the net,” Olm shrieked, as both he and the mushroom man were pummeled by the flat end of the spears.

Poison Pie struggled and strained but the strength of the net far exceeded his own. After a few moments, he decided his hands would be better served covering his face and preventing it from being beaten black and blue.

“Break the net,” Olm screamed again, though he too was covering his face.

“I can’t,” Poison Pie mumbled through his hands. “I’m not strong enough.”

“A net is nothing to the Champion of the Deadly Galerina! You’re not calling upon it for strength!” His voice was thick with accusation.

It was true, Poison Pie admitted to himself as the beating continued. He was not calling upon the Deadly Galerina. He had very little history with any such creature and he felt it quite unlikely that any plea in this hour of need would meet with a sympathetic ear. Besides, what would he ask the Deadly Galerina to do? The shaft of a spear slipped between his arms and struck him hard in the ribs. Perhaps he should ask the Deadly Galerina to turn all the spears into long, soft, wet noodles. That would certainly be an advantageous turn of events. However, Poison Pie doubted that the Deadly Galerina would condescend to such divine intervention.

A blow hit him in the back of the head and Poison Pie saw stars. In the stars, he looked for a secret, celestial message from the Deadly Galerina. A message emerged but it seemed both not very relevant to their present situation as well as virtually certain to irritate Olm. Nevertheless, Poison Pie knew not what else to do.

“In the name of the Deadly Galerina,” Poison Pie shouted over the tumult, “I forgive you all for being born troglodytes, senseless brutes who know nothing but might through violence.”

Olm had only a moment to register his incredulous dismay at the words of his Champion, before he was knocked unconscious by a well-aimed blow. Poison Pie was soon to follow him into darkness.

|

|

|

|

|

April 22 & 23, 2014

Poison Pie dreamt unpleasantly. The sensations bombarding his nervous system carried contradictory messages. He seemed bound, his movements constricted. Neither his arms nor his legs would obey the commands of his brain to rise. At the same time, he seemed possessed of an entirely different sort of mobility. His body was expanding, taking on cells, growing new appendages...no that wasn’t it...rather becoming attached to pre-existing appendages, which had previously been no part of him. As his body grew, so did his memory for each new cell brought with it a genetic tradition that spanned millennia. Poison Pie quickly realized that this entity into which he was quickly being transformed was ancient and not at all human. There was no aspect of mushroom man about it; it was purely fungal. It crept in every direction via countless plasmodia. It sensed from every surface. Ten thousand troglodytes moved simultaneously within its innards. Offered upon the central altar in the Temple of the Deadly Galerina, Poison Pie was merging with the City that Crawls.

It was not as glorious a transformation as it sounded. Poison Pie could not open his eyes and thus he was unaware of the web of white fungal filaments that had enveloped him and now held him fast to the stone altar. He could not turn his head to observe a similar fate overcoming Proteus Olm, albeit on a smaller altar situated on a lower tier of the dais.

Poison Pie opened something—some sensory organ with which he had not previously been familiar—and heard a faint cry as Olm’s consciousness also dissolved into the city. Far from the curious sensations that seemed to both soothe and perplex Poison Pie, Olm seemed to respond with abject terror. It was not so bad, thought Poison Pie. The City that Crawls was insensate but possessed a wisdom and memory similar to that of the inanimate, a wisdom which for him had always possessed some allure.

The City that Crawls found no resistance in Poison Pie, who not only understood but embraced the idea that events transpire without reason or purpose. He found no objection to this manner of passing. It was neither painful nor pleasurable. His destination remained satisfactorily unknown. Would remnants of consciousness wander endlessly within the mental cavities of the City that Crawls? Would his essence eventually become so diluted that he would simply dissipate? Would the moment in which he ceased recognizing himself as Poison Pie pass gratefully without witness or comment by anyone anywhere?

“Finally,” Poison Pie thought to himself, “Here I go.” In his opinion, he had existed sufficiently long and he had never come to comfortable terms with his own existence, though he undeniably had had ample opportunity to do so. Thus he greeted this transformation, which he interpreted to be the onset of cessation, with no small degree of ambivalence. At this thought, his spirit, such as it was, seemed overcome by an ineffable buoyancy. He rose through the structure of the City that Crawls. He heard the ring of priests chanting around him. Their prayers to the Deadly Galerina made perfect sense to that being which had once been Poison Pie. Although he had never worshiped the Deadly Galerina, it suddenly appeared to him as not only a viable but attractive option. It seemed an avenue by which one might make sense of the world, and through this understanding make better sense of one’s role within it. “Is this a divine revelation?” that which was once Poison Pie thought to himself.

In his excitement, he drifted further from his body. He traveled simultaneously backward and forward in time. He shrunk in the memory of the City that Crawls back all the way to a single spore placed carefully by a gentle hand in a damp fissure of stone. Poison Pie strained to change his point of view and observe the face associated with that hand, but such control was beyond his power. Thus the appearance and identity of the one to whom the City that Crawled owed its origin remained a mystery.

That being who was once Poison Pie was further transported through the cellular matrix of the City to the outskirts where the troglodyte hatchling ponds were tended by meticulous females. As he tasted the birthing liquids, the futures of the next generation were laid open to him as if written in a book. He stretched to the limits of the city and stretched toward the darkness of the deeps surrounding him. “There, into the darkness, shall I go,” he thought.

But Poison Pie did not venture into the darkness for at that moment, the tendrils on the temple altar had penetrated the flesh between his ribs and encountered twice what they expected—two hearts, one flesh and one stone. The flesh they recognized as a familiar consumable. The stone they also recognized, but as something entirely different, something that triggered a response written in their DNA.

Gorgonio!

The reaction was immediate and traveled from that central point in nervous system of the City that Crawls as a shudder that spread to the extremes of all its appendages. The cellular matrix pulsed with light and undulated, emitting low moans as mechanical stress built up in tissue neither accustomed to nor intended for such service. The nursery pools overflowed. Pillars buckled. Doorways either shattered or burst from their hinges whole. The initial shudder reached the outskirts of the city, where Poison Pie lingered, then was reflected back onto secondary waves. These waves coupled with each other and the magnitude of the tremors grew.

Poison Pie reluctantly observed this rapidly accelerating destructive activity. He had been so close to the darkness. He thought to cast his gaze at it again, but the stretch of flesh in which he had been coiled was shriveling and being pulled back by tensile forces. Poison Pie himself was drawn against his will back into the City. He knew, somehow, that the pink marble heart, which he had brought into the city was the cause of these growing reverberations that threatened to destroy the entire structure.

He was sucked back by the city itself, by a power far greater than his own, snapped back like a strip of rubber, tumbling head over heels, despite his disembodied state, until he arrived again in the temple’s central, sacrificial chamber. He saw now, though what eyes he used were not clear to him, his own body lain out on the altar. He was covered in a skin-tight shroud of white tendrils, turned pink with the intimation of blood where the individual tongues had entered his pores. Neither he nor Olm beside him breathed. Those bodies were husks from which the life energy and nutrients had already been drained. But whereas Olm’s body had collapsed in upon itself, Poison Pie’s body resisted.

The pace and volume of the chant of the circle of troglodyte priests increased in urgency. The tell-tale stench of troglodyte stress gradually filled the chamber. The priests seemed to be calling for the destruction of Poison Pie’s body, a task at which the City had at first acquiesced. However, the City had now discovered the stone heart and the heart was unpalatable. The City began to withdraw its tendrils. The body of Poison Pie convulsed. Poison Pie found himself rooting for his old body to succeed in whatever bizarre endeavor in which it was now engaged, though he still harbored no desire to return to it.

As the white fungus receded, panic seemed to spread among the priests. When it seemed clear that no amount of vehement chanting would turn the tide, one priest cried, “It is as Olm said! The mushroom man is a Champion of the Deadly Galerina!” This vocalization of his fear weakened the group and hastened the retreat of the white fungus. The stench of troglodyte panic now grew so thick that it became a palpable impediment to further organized action on the part of the priests.

At this point, Poison Pie was alarmed to discover that the faint tattoos, ostensibly containing the text of the letter he had eaten, now appeared in clear, well-defined dark brown characters all over his old body.

Illiterate in every language, the words meant nothing to Poison Pie, but the eyes of the elder priest’s opened wide in sheer horror. They shouted for the brotherhood of priests to reassemble. A feeble attempt followed to reform their ranks, but it proved too late. There was no redoing what had come undone. The air grew thick and close with troglodyte panic so concentrated that it began to condense in a thin, slimy film on the fungal walls of the temple.

Poison Pie, much to his dismay, was spat back into this body as if he were the pit of a cherry from which all of the sweet flesh had been stripped clean. He sat up abruptly and examined the meaningless messages across his arms, belly, genitals and legs. To make matters worse, his return to a corporeal form exposed him to the physical odor, which threatened to overwhelm him. He coughed and choked. Mucus closed his nose and gathered at the corners of his eyes.

The circle of disordered priests surged backward a step.

Poison Pie rose to stand between his vacant slab and that upon which the remains of Olm still lay. He meant to rest a compassionate mitt (now most offensively tattooed) on the brow of the priest, but the husk that remained collapsed under the weight of his hand, drawing a gasp from the assembled troglodytes.

Beset by streaming tears, Poison Pie bellowed, “I am the Champion of the Deadly Galerina!” for there was no other explanation that seemed to explain why his fate was different than that of Olm. He still did not at this time recognize the role of the pink marble heart.

His declaration sent the priests racing out of the room. Several brave soldiers rushed in, after the priests’ departure, and thrust spears at Poison Pie. Despite the continued onslaught of the troglodyte stink, the movements of the soldiers seemed clumsy to Poison Pie, as if they were trudging through molasses. He brushed the spears easily aside. He made as if to shove them back but hesitated, overcome by a realization that their frail bodies might offer no more resistance to him than the husk of Olm.

The soldiers, sensing this moment of reprieve, fled from the temple.

“Poison Pie,” said the City that Crawls in a voice that issued from every orifice in the city, “I have opened the door for you.”

Poison Pie turned and examined a shimmering portal that had mysteriously appeared in the mushroom wall of the chamber.

There was no sense putting any questions to the voice. There was no point in asking where the door led, because even if the voice had condescended to answer, there was no advantage in knowing one’s destination ahead of time, or so thought Poison Pie, quite the contrary. Consequently, he strode naked, tattooed mitts swinging at his sides, across the trembling floor of the temple through the portal, which seemed to flinch as he entered it.

The portal entered a series of spasms, which would result in a matter of a few seconds in the closing of the passage. In the time that remained, Celia and Tchict’Ict, hands clasped over their mouths, raced into chamber, observed Poison Pie’s departure and dove through the portal themselves before it disappeared into nothingness.

|

|

|

|

|

3. Nirvana

|

|

|

April 23, 2014

Nirvaṇa literally means “blown out”, as in a candle. The attainment of Nirvana is associated with the liberation from the cycle of rebirth in the Earthly realm, which, by its nature, is a state of suffering. In the Buddhist context Nirvana refers to the imperturbable stillness of mind after the fires of desire, aversion, and delusion have been finally extinguished. In Hindu philosophy, it is the union with the divine essence of existence, as represented in a Supreme Being, and the experience of the blissful absence of ego.

—adapted from wikipedia

|

|

|

|

|

April 28, 2014

We begin again, this time under a distinctly different sky; slate gray clouds casting an evening shadow over the midday hours. An expectation of rain hung thick in the air, though none had fallen yet, as evidenced by the dry dust on the road and the parched scrub grasses that lined it. Poison Pie examined the landscape before him, a rough, hard-scrabble country across which isolated trees were scattered. In the far distance, a ridge of gray hills formed the horizon. To his right, a small, solitary mountain rose. It seemed to Poison Pie that the amount of flora increased with elevation, as judged by the gradual shift in color from the ochre flanks of the mountain to its comparatively verdant summit. The mushroom man scanned ahead again, looking for some indication of a destination, smoke rising from a chimney or patterns in the earth indicating furrowed fields. Instead, all he sensed was that this land seems a place where wounded animals, stubborn enough to escape the predator’s jaws or the hunter’s killing blow, retreated to expire in isolation from their injuries. Poison Pie expelled a deep breath, but the sense of desolation, inspired by the forlorn countryside or something less tangible, did not leave him.

“Where are we?” asked a familiar, chittering voice from behind him.

Poison Pie was startled. He had imagined he was alone. He turned to find not only the insect man but the monk as well, still maintaining her reptilian guise as a troglodyte. Immediately, his spirits rose. The land seemed somehow less foreboding in the company of his traveling companions. Poison Pie released an elaborate shrug, shoulders rolled and his mitts rose momentarily in the air. “I don’t know,” he admitted.

“In some respects, it reminds me of my ancestral home,” Tchict’Ict added.

Such a declaration surprised Poison Pie not in the least. Tchict’Ict carried with him an air of strict practicality, which suggested he had been raised in a land that provided only the bare minimum for survival, a kind of impoverished environment now inseparable from the insect man himself.

Poison Pie shifted his gaze to Celia, the monk, thinking perhaps she had some clue as to their current whereabouts.

“Don’t look at me,” she replied, “my earliest memories are of a forest.” She could, of course, not speak of ancestral lands, since doppelgängers were traditionally nomadic, under the best circumstances being driven from whatever place they had settled as soon as their true natures were discovered.

They debated for a short while the direction of their travel. The dusty path led to the hills on the horizon. The green summit of the nearby mountain beckoned them. In the end, necessity made their decision for them. They had arrived ill-equipped. It might take them several days to walk the length of the rocky wasteland before them and there was no hint of water, save that in the clouds above. They opted to see what provisions they could gather at the mountaintop before pursuing the path.

It was, not surprisingly, a foreordained decision. There was no path to the foot of the mountain, but the brush was so thin that the terrain proved not too difficult to traverse. Once there, the slope of the mountain was sufficiently steep that they found themselves following natural cutbacks in the stone, rather than scaling the mountainside directly. The cutbacks seemed to gradually guide them to the far side of the mountain, at which point the rain began to fall in large, fat drops.

The three hikers stopped and let the water clean the dust from their skin. Two of them opened their mouths and drank what rain entered. Tchict’Ict formed a makeshift cup from the broad leaf of a bush that grew only at this elevation and expertly caught a thousand raindrops in a matter of minutes, which he then arranged between his mandibles and poured into his mouth. Observing the insect man’s technique, first the mushroom man then the monk tried to fold similar leaves into the appropriate shape and catch the rain as well. The clouds were patient and continued to provide rain, which was a good thing, since neither proved the equal of the insect man in gathering rain in this way. In truth, even among the insect men, it was a skill that took many years to master. They were not satisfied until Tchict’Ict had filled several cups in this manner and distributed them equally.

Their thirst slaked, the continued up the mountain, finding the going no more difficult though the density of the foliage increased considerably. They seemed to have stumbled upon a path, a suspicion which was confirmed when it led them to a narrow staircase, carved into the stone and leading further up the mountain. They ascended single file, with Poison Pie in the lead and Celia in the rear. They remained alert, though there was no sensation of danger. The mountaintop jungle, for that is what it quickly became, seemed innocuous compared to the dusty wasteland spreading out from its base.

They passed a variety of fruits and nuts hanging far above their heads in the trees. Tchict’Ict offered to scale them and retrieve a meal for all, but was discouraged by the monk. They did not know which species were fit to eat and were not yet at a point of dire need where they were driven to sample strange, potentially poisonous, fruits. The same was said also of the mushrooms they found growing in the shade of the trees.

“Do you eat mushrooms?” Tchict’Ict asked absently, as he hiked behind Poison Pie.

Poison Pie, who had frequently consumed all manner of fungi without a second thought, now was struck by the manner in the insect man asked the question, as if this were a quiz in which his status as cannibal hung in the balance.

“Do you eat insects?” Poison Pie replied, excessively pleased with himself for rather deftly (so he thought) avoiding the question.

“Indeed,” said Tchict’Ict. For the next ten minutes, the insect man regaled his companions with the nutritional benefits and culinary delights of fat, juicy grubs, particularly the larvae of a certain species of beetle known only in his tribal lands. Many skirmishes, he promised them, had been fought over the breeding grounds of those beetles in which the larvae were harvested. In truth, neither Poison Pie nor Celia had ever heard the insect man speak so eloquently or at such length on any topic. They concluded that he must be quite hungry. His original question of Poison Pie was forgotten or politely abandoned.

In total, nearly nine hours elapsed before they reached the summit. The last two hours were entirely occupied by carefully climbing the rain-slick stone stairs, which were bordered by the steep stone face of the mountain on one side and a precipitous fall on the other. At times the stairs were shadowed by overhanging trees growing from small shelves on the mountain. In one place, the stairs were completely submerged in a stream cascading down the mountainside. When the stones finally opened up to a plateau, the plant growth was so thick that they had no clear idea of the size of the area. A path led through the woods, though it was overgrown and both Poison Pie and Tchict’Ict were forced to stoop nearly bent double at the waist. With every step they disturbed the leaves around and above them, causing water to empty from the crevices and vanes, onto their heads and backs.

After a few hundred yards, the travelers found themselves in a clearing. A pond acted as a moat keeping the bigger trees at bay. Upon the surface of the water, lily pads bearing yellow blossoms gathered in dense clusters. Inside the moat, an island rose, upon which the jungle did not encroach. The surface of the island was a mixture of moss covered stone, small plants, and oddly shaped flowers. The landscaping struck the companions as quite pleasing and they wondered if it had in fact been cultivated. Such an idea was not so preposterous given that at the center of the island, a structure, which one might call a pagoda for lack of any more accurate term, stood. It was entirely composed of living wood, vines which had been woven when young, thin and supple, but had long ago hardened into intertwined, trunks of six or eight inches in diameter. The octagonal structure was open, with eight of these living pillars at the perimeter, rising individually, before spreading over the pavilion and becoming enmeshed in a tangle of branches and leaves that formed the ceiling, which seemed to deflect most of the water such that it dripped along the perimeter and ran in rivulets to the moat.

The floor of the pagoda was constructed of wooden planks, perhaps bamboo or something like it. The furnishings were sparse—a central embroidered rug, upon which an elaborately embroidered pillow sat. Upon the pillow they found a monk, who seemed both ancient and youthful. Not a strand of white was to be found in his black hair, not a whisker on his chin or a wrinkle in the flesh of his face. Nevertheless, as he sat in a meditative pose upon the pillow, his eyes betrayed an age that no manner of contrary physical characteristics could deny. The monk was garbed in a saffron robe and seemed not at all surprised by the arrival of his visitors, who lined up in front of the pavilion, separated from the monk by the curtain of water that fell from the edge of the roof. In truth the imperturbable expression of the monk seems more remarkable if one remembers the appearance of these visitors—a man of the mushroom people, naked and tattooed from head to toe in an alien, dark brown script, a four-armed insect man bearing wicked blades attached to two shields and both ends of a pole, and a smelly, troglodyte female wearing a soaking wet, ill-fitting gray shirt and trousers.

“Come in, out of the rain,” beckoned the monk, with a fluid gesture of his fingers.

As he stepped forward, Poison Pie found a narrow gap in the sheet of water. Tchict’Ict and Celia slipped in behind him. They dripped on the wooden floor, though the monk paid it no mind.

The monk gestured for them to sit and they obeyed, finding places among the puddles. The monk examined them only briefly but discerned that their first need was for food. He rose without explanation and disappeared through a slit in the curtain of rain in the rear of the pagoda. Through this film, his movements were blurred to the occupants within. The monk emerged, curiously dry, bearing a tray. From this tray, he served each of his guests, a wooden bowl filled with nuts and dried fruit. He then poured into rough, wooden cups a sweet, fruity beverage, which simultaneously rejuvenated them and set them at ease. As his guests ate, the monk seemed to join them, though when their bowls were empty, the contents of his bowl seemed untouched.

“Now sleep,” the monk suggested and the trio spread out on the carpet and slept, those questions that had only moments before been bursting to escape, forgotten for the moment. “And dream,” he added with an inscrutable smile, knowing full well his listeners were already well on their way.

|

|

|

|

|

April 28, 2014

Poison Pie dreamt he was someone else. There was no external indication that he was no longer Poison Pie, but in the dream this certainty needed no evidence. Poison Pie was someone else, unknown but vaguely familiar to him. Poison Pie could not remember the name, if he had ever known it. This being in whom Poison Pie now found himself walked the same desolate lands that he had walked earlier in the day. It was as if Poison Pie was a shadow attached to the feet of this other being, dragged over the stone. However, the lands seemed somehow less forlorn in the presence of this other being. There was more green in the land. The same dry path that Poison Pie had left earlier now followed the path of a stream, on the banks of which grew patches of clover and wild strawberries, sporting tiny purple flowers. It seemed to Poison Pie that this memory of the land had been captured a long time ago. Poison Pie carried a parcel under his arm—a wooden box. It was clearly a gift for someone. Poison Pie experienced the emotional sensations that a gift-giver knows when one has found the “perfect gift” and is sure that its reception will go positively well.

Poison Pie felt the contentment of the gift giver. Strangely, he also began to experience the pleasure of the recipient of the gift. In the dream, he engaged in an unexpected and not entirely welcome transformation from giver to recipient. At the end of this stomach-churning change, he held the gift again and was immensely grateful. All sense of discomfort disappeared. There was only disorientation in the transition and he understood nothing of its origin. Of course, this is Poison Pie we are talking about, so the lack of understanding troubled him not in the least. Poison Pie was a Champion of the Mushroom People, with a well-calloused hide rendered impermeable by the trials of time to the arrows of reason.

|

|

|

|

|

April 28, 2014

Celia dreamt. Her dreams followed the action of a text she had read in the monastery. The text was perhaps five hundred years old but recounted events a thousand years older. The text related the travels of a historical monk, Tang, who was sent by the emperor of his homeland to a land far to the south, in order to retrieve a set of scriptures and return with them, that the empire might further blossom under the beneficent guidance of these writings. The journey promised to be dangerous and the monk lacked both worldly wisdom as well as any ability to defend himself from the very real threats of physical danger that were sure to plague him on his way. Thus, a Bodhisattva sent supernatural disciples to protect Tang along his journey. One such companion was a buffoon, an entirely unpredictable monkey-man, who lacked impulse control and who fancied himself the “Great Sage Equal to Heaven”. Another companion was a gluttonous pig-man.

In Celia’s dream, their host in the pavilion set down the ancient text. He then explained to her that she too had been assigned a mission to retrieve a lost scripture.

Of course, Celia explained to her host that he was sadly mistaken. She was merely accompanying Poison Pie; it was not her quest. Her host raised an eyebrow; his doubt silencing Celia’s objections.

“Celia,” said the monk, “if Tang could retrieve the Heart Sutra of the Perfection of Wisdom, from the far southern lands separated from his home by the great mountains, accompanied by a monkey-man and a pig-man, it should not require any great stretch of your imagination to accept that your companions, a mushroom-man and an insect man, have been provided by the Bodhisattva to aid you on your own endeavor.”

Ashamed that she had allowed her thoughts to become so clouded that the obvious was hidden from her, Celia fell to silence and bowed her head in obeisance.

|

|

|

|

|

April 28, 2014

Tchict’Ict dreamt as only insects dream, as a manifestation of biological processes of the subconscious designed to reduce mental stress that had accumulated during the waking hours. Insects know a variety of stress uncommon among mammals, for insects never invented a supernatural realm. Thus, where mammals attribute inspiration or revelation received during a dreaming state to the intercession of a divine entity, Tchict’Ict had no such interpretation available to him. We have already revealed that the mere thought of becoming an object of interest to an agent of the Insect Gods brought Tchict’Ict the deepest discomfort.

Tchict’Ict’s host’s knowledge of the insect world was no less than his knowledge of the mammalian, reptilian or fungal worlds. He therefore spared Tchict’Ict dreams in which disturbing, transcendental messages were relayed.

Instead Tchict’Ict dreamt the traditional dreams of insects. The colony queen rose in their air on gossamer wings. She released her best pheromones in the air that worked to lull the gathered throng, Tchict’Ict among them, into a hypnotic trance. She performed an arthropoid musical duet in which the high frequency vibrations of the beating of her wings provided a background cadence to the chirruping song that emerged from her thorax. Tchict’Ict found the song utterly intoxicating. Although the sensation threatened to overwhelm him, he opened his pheromone receptors to their fullest capacity in order to maximize the experience.

For insects, who do not dream of a purpose beyond the biological, of a soul or any element of being beyond the physiological, or of an afterlife beyond the physical existence, the acknowledgment of the purely experiential nature of their intellect provides a sense of euphoria that captures exactly a distilled purity of the perception that renders every instant of their lives meaningful. Such, for Tchict’Ict, was the dream visited upon him by their host, a dream the comfort of which this journey promised to take from him, though he knew it not.

|

|

|

|

|

April 28, 2014

The Heart Sutra of the Perfection of Wisdom

When the Bodhisattva Kuan-tzu-tsai was moving in the deep course of the Perfection of Wisdom, she saw that the five heaps were but emptiness, and she transcended all suffering.

Sariputra, form is no different from emptiness, emptiness no different from form; form is emptiness, and emptiness is form. Of sensations, perceptions, volition, and consciousness, the same is also true.

Sariputra, it is thus that all dharmas are but empty appearances, neither produced nor destroyed, neither defiled nor pure, neither increasing nor decreasing. This is why in emptiness there are no forms and no sensations, perceptions, volition, or consciousness.

There is no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, nor mind; no sight, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, nor object of mind. There is no realm of sight, no realm of sound, nor smell, nor taste, nor touch, nor realm of mind-consciousness.

There is no ignorance and no extinction of ignorance. There is no old age and death, nor cessation of old age and death. There is no suffering, no causes of suffering, and no cessation of suffering. There is no path, no wisdom, no attaining wisdom, and no not-attaining it.

Because there is nothing to be attained, the mind of the Bodhisattva, by virtue of reliance upon the Perfection of Wisdom, has no hindrances, and therefore, no terror or fear; he is far removed from error and delusion, and finally reaches Nirvana.

All the Buddhas of the past, present, and future rely on the Perfection of Wisdom, and that is why they attain the ultimate and complete enlightenment.

Know, therefore, that the Perfection of Wisdom is a great spell, a spell of great illumination, a spell without superior, and a spell without equal. Truly, it can do away with all suffering.

The mantra of the perfection of wisdom spoken: Gone, gone, gone beyond, completely gone beyond! Awakened! So be it.

|

|

|

|

|

April 28, 2014

The party awoke to find their host seated again on the pillow at the center of the pavilion. If he had been chanting while they slept, only the faintest echo of that chant remained in the air and, as the last remnants of sleep dissipated from their minds, that echo faded into silence. The rain had stopped and a morning light filtered through the clouds into the clearing around the pagoda. Each guest rose to a sitting position. Although they had slept on what should have proven to be a hard surface, their bodies felt replenished and free of stiffness. Each in turn noticed that in front of the monk sat a wooden box, which Poison Pie immediately recognized from his dream.

Before Poison Pie could ask about the curious appearance of the box, Celia voiced a question of her own, “Are you the original Sariputra?” Poison Pie understood that just as his question had originated in a dream, so too had Celia’s.

The ageless monk only smiled and agreeably but ambiguously said, “You are welcome to call me Sariputra.”

“Sariputra,” Celia obliged, “have you been reciting the Heart Sutra?”

“Oh, a favorite of mine,” Sariputra exclaimed, again not answering the question. “Would you do me the kind favor of reciting it?”

Celia, even in troglodyte form, appeared abashed. To recite the Heart Sutra in front of one, who might be the original Sariputra to whom the Heart Sutra was first given, was too great an honor for her to accept. She begged out of it but, though the monk offered no words of contradiction, eventually she sensed that her refusal would bring their host only disappointment. Thus she rose to her feet and recited the Heart Sutra of the Perfection of Wisdom. Celia ended, saying, “Gone, gone, gone beyond, completely gone beyond! Awakened! So be it.”

Poison Pie rubbed his eyes because Celia, even in her repulsive troglodyte form, seemed to be glowing and, if he was not mistaken, hovering over the pavilion floor. When his vision returned, nothing was amiss, but his memory stubbornly refused to dismiss the vision as purely a figment of his imagination.

Sariputra too seemed to be illuminated by an inner glow, as if his heart was a lantern and his skin had adopted a degree of translucency.

Celia, slightly embarrassed, sat back down. “I don’t know why you needed me to recite it.”

Sariputra proved surprisingly candid on this point and answered her, saying, “It is my intention to have every being who has ever lived recite the Heart Sutra. Now I can cross you off my list.”

Poison Pie fidgeted nervously wondering if he next would be asked to recite the sutra. He struggled to remember the words that he had heard Celia just recite. “There is no realm of mind-consciousness,” he whispered to himself before giving up. He stole a glance at their host to see if his fears would materialize, but the monk was still glowing, apparently blissfully oblivious to the mental machinations of Poison Pie.

Sariputra said nothing of the box but instead served a breakfast very similar to the meal of the previous evening. After eating, Poison Pie motioned a mitt to the box. “What’s in there?”

“You tell me,” said Sariputra. “You left it the last time you were here, telling me only that I should give it back to you upon your return.” Sariputra revealed no acknowledgment of Poison Pie’s expression of incomprehension, instead opting to add nonchalantly, “That was some time ago,” as if anybody could have forgotten about such a non-descript box after so much time had passed.

Poison Pie turned to find Tchict’Ict and Celia fixing him with curious faces. The mushroom man took a deep breath, during which he began to mentally prepare a long-winded disclaimer in which he disavowed any knowledge of this place, Sariputra, the box or its contents. His ability to address this issue seemed to focus a tension within himself that was at odds with the serenity of the pagoda. In this internal strife, tension succumbed to serenity and Poison Pie exhaled without uttering any explanation at all.

His two companions, for their part, did not press him on this point. Instead, they watched him rise and approach the box. He knelt down and opened it and withdrew a pair of pale gray trousers and shirt, which matched to a disconcerting degree, the monk’s garb, which Celia wore, only a dozen sizes larger. Poison Pie had tolerated for too long being naked and quickly donned the clothes despite the fact that he had little intention of associating himself with monks, who practiced a lifestyle that held no particular attraction for him and posed more than a little trepidation. Next Poison Pie withdrew sandals that fit his splayed feet perfectly. Poison Pie then withdrew three empty bladders, attached to straps, which could be slung over the shoulder. Sariputra gestured to a rain barrel behind him and suggested that they be filled prior to their departure as there was now little water to be found along their path.

From the bottom of the wooden box, Poison Pie withdrew a slender book, clasped shut with a fine filigree lock. He searched for a key but found the box now empty. Poison Pie rose again to his feet and examined the cover of the book at arm’s length. He felt fairly certain that the characters on the cover of the box matched those now printed on his flesh, an observation which brought him no joy whatsoever. He had eaten the letter. Did he have to eat this whole book as well?

“Well, I can’t read this,” he said, showing none of the reticence before Sariputra that he had previously felt upon revealing his illiteracy to others. It seemed to him that, at least up here on his mountaintop hermitage, there were no secrets from Sariputra.

Sariputra’s eyes glanced casually at the book as Poison Pie held it out for his examination.

“It must be for you,” Poison Pie concluded, stretching out the book to Sariputra.

“Ever so generous,” Sariputra said in a complimentary tone. He gracefully reached forward and took the slender volume in one hand. “Before I accept this, Poison Pie,” said Sariputra, though Poison Pie felt sure that he had never introduced himself by name to the monk (a point which only reaffirmed his suspicion that no secrets could be kept here), “let me first translate the title of this book.”

Interrupting Poison Pie’s forthcoming objection, Celia quickly interjected, “Oh, we would be so grateful if you did.”

Sariputra smiled obligingly. “Of course, for you, my lady,” he said with such composure that for a moment Poison Pie could almost imagine Celia as a regal noblewoman and not the ugly troglodyte seated in a lump on the pavilion floor. It nearly dawned on Poison Pie that Sariputra saw no such creature.

“This book provides ‘an equality of runes’, such as those covering your skin,” here Sariputra nodded deferentially to Poison Pie, “and more common scripts known to the races that populate the lands of this contemporary time. It is essentially a means for translating the message you have so well already internalized.” Sariputra offered the book back to Poison Pie. “Although I sincerely thank you for the offer, I don’t think that I am the intended recipient of the gift.”

Poison Pie could but agree with the monk, who presumably already knew very well the nature of the message scrawled on his skin and remained silent on the manner due to either a sense of well-bred discretion or some cosmic oath binding his tongue or, maybe, both.

Reluctantly, Poison Pie handed the thin volume to Celia, who, though she had said nothing, was practically begging for the book. It disappeared quickly within her pack.

As they prepared to depart, they filled the water bladders and accepted the provisions that Sariputra offered them. As they headed for the path from clearing to the edge of the jungle, Sariputra followed them only as far as the edge of the pavilion. “Poison Pie” he called.

All three travelers turned to him, for he apparently had some parting words.

“You will not find this land as you last left it.”

“I don’t understand what you mean,” Poison Pie admitted, at a loss for any more eloquent words by which he might express himself. “I’ve never been here before,” even as he spoke the words, he heard a ring of untruth in them.

Sariputra led the ringing subside before continuing. “This place, Nirvana, formerly reachable only through the extinction of suffering, is now accessible by other paths. The realm beyond mind-consciousness once thought eternal is undergoing a renovation of sorts.”

Even Poison Pie understood enough of the elements of the immutability of eternity to reply, “That seems highly unlikely.”

“The probability of an event transpiring is better understood only by considering the relative probabilities of all the alternative events that did not come to pass,” said Sariputra. “Though it matters to you little; you must seek out the Deadly Galerina, who long ago found a serenity fashioned to suit its own peculiar tastes in this land.”

Poison Pie nodded. He took the monk’s words as a dismissal and headed to the gap in the encircling jungle.

“And you, Celia,” said Sariputra, “would do well to change the form of your disguise. That form will not be welcomed outside this mountain retreat.”

Celia bowed. “Thank you, Master, for your concern for one such as I, who does not deserve to dwell a mere second in your illustrious thoughts.” She too headed off into the jungle.

Tchict’Ict paused momentarily, thinking there might be a parting message from the monk for him as well.

Sensing the insect man’s delay, Sariputra smiled and waited until the other two were out of earshot. “Tchict’Ict,” said Sariputra, “It falls to you, most unlikely of heroes, to take care of those two. Understand that their failure and your subsequent doom bear no reflection on the virtue of your actions. It brings me neither relief nor joy to share this knowledge. Such is it written.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This work is made available to the public, free of charge and on an anonymous basis. However, copyright remains with the author. Reproduction and distribution without the publisher's consent is prohibited. Links to the work should be made to the main page of the novel.

|

|

|

|

|

|